Book Review: The Stack & Tilt Swing - Michael Bennett and Andy Plummer

Click here to go to the index page.

Introduction:

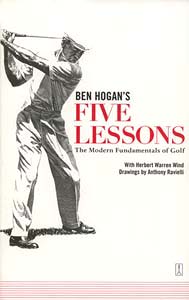

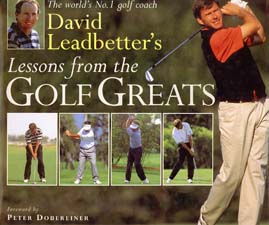

In this critical scholarly review paper, I will be discussing the Stack & Tilt (S&T) swing. One of the primary purposes of the review paper is to first discuss the fundamental philosophy underlying the development of the S&T swing. I will then discuss how Bennett/Plummer recommend that their S&T swing be executed from a practical standpoint. In my brief description of their swing methodology, I will only be providing enough detail to demonstrate how Bennett/Plummer's practical advice subserves their fundamental swing theory. Golfers who want to learn how to execute the S&T swing need to buy Bennett/Plummer's book [1] or DVDs, and/or obtain tailored advice from a S&T instructor. After reviewing the S&T swing, I will then compare it to the philosophy, and practical execution, of the traditional (conventional) golf swing, and I will also provide a detailed argument that expands on the many reasons why I personally believe that golfers should not adopt the S&T swing - i) primarily because it is based on biomechanically unnatural movements and ii) secondarily because I believe that it is very likely to cause chronic back problems over the long-term. After reading this review paper, website visitors should independently decide whether my detailed arguments have any intellectual/scientific merit, and they are always free to accept, or reject, my personal opinions.

I first became aware of the S&T swing, when Bennett/Plummer published an article on their swing methodology in the June 2007 issue of Golf Digest magazine. I then wrote a review paper in July 2007 called "Critical Review: Aaron Baddeley's New Swing - The Swing Methodology of Mike Bennett and Andy Plummer". My main interest in writing the review paper was related to a chance-event - the fact that I arbitrarily used Aaron Baddeley as a role model for the traditional golf swing when I first started my golf website in December 2006. When I started my golf instructional website, I looked about for a golf swing video where the professional golfer had a simple, but traditional, swing. I also wanted a good quality swing video, so that I could produce capture images for my website's basic chapters on the modern, total body golf swing. I found a good quality swing video of Aaron Baddeley's swing at the V1 Home website, and I therefore decided to use Aaron Baddeley as my role model. In their Golf Digest article, Bennett/Plummer also used Aaron Baddeley as their role model for their S&T swing, and I was obviously curious as to why Aaron Baddeley decided to change his swing style in 2007. My personal understanding of the S&T swing in July 2007 was limited by the fact that I could only depend on the limited amount of detail provided in the two-part Golf Digest article. Now that Bennett/Plummer have published their book [1] on the S&T swing, I have had the opportunity to acquire a much deeper understanding of their golf swing philosophy and golf swing methodology. Therefore, my opinions expressed in this review paper supercede my opinions expressed in my July 2007 review paper.

The Stack & Tilt swing philosophy:

In his book on the mechanics, physics and geometry of the golf swing [2], Homer Kelley stated that there are three imperatives in a golf swing and three essentials - and when combined together they represent the fundamental TGM principles of a golf swing. The six TGM fundamentals are a i) a flat left wrist; ii) a clubhead lag pressure point; iii) a straight plane line; iv) a stationary head; v) balance and vi) rhythm. I have discussed the importance of these TGM fundamentals in my previous review papers (and accompanying swing video lessons). By contrast, Bennett/Plummer have a totally different list of fundamentals.

Bennett/Plummer state that there are three fundamentals and they state-: "We teach three fundamentals, to be followed in this order: (1) hitting the ground in the same place every time; (2) having enough power to play the course; and (3) matching the clubface to the swing path to control direction. ----- The first measurable difference between golfers of different skill levels is the ability to hit the ground in the same place time after time - in other words, the ability to control the low point of the swing."

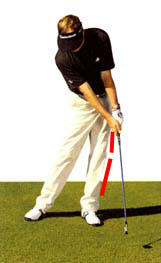

Bennett/Plummer correctly place a great deal of emphasis on a golfer's ability to have the low point of the swing at the same place on the ground in swing-after-swing, and they use the following photograph to demonstrate that fundamental point.

Hitting the ground at the same place - from reference number [1]

Note that the divots are always in the same place - just ahead of the white line, and just behind the left heel.What allows a skilled golfer to consistently hit the ground at the same spot in repeat swings, and thereby have the same low point location in swing-after-swing?

Bennett/Plummer provide their *arbitrary answer on page 6 of their book [1]. They state-: "The first factor that contributes to the location of the low point is where the body weight is at impact. We measure the weight by locating the swing's two centers - the center of the shoulders (above the sternum) and the center of the hips or pelvis. If the swing's dynamic center, which is the combination of the shoulder and hip centers, is back too far, the swing tends to bottom out behind the ball. If the dynamic center is forward, the swing tends to bottom out in front of the ball."

(* I personally disagree with Bennett/Plummer's assertion, because I believe that the location of low point has no absolutely necessary causal connection with the position of the two swing centers at impact - and I will discuss my personal viewpoint in great detail in a later section of this review paper).

Bennett/Plummer acknowledge that another factor affects low point - and that is the timing of the club release phenomenon and the degree of forward shaft lean at impact. However, they obviously place major emphasis on the importance of the location of the swing centers at impact.

When discussing the swing centers, Bennett/Plummer primarily discuss the importance of the upper swing center - which is a point in front of the spine, roughly at the base of the neck, and it is located midway between the shoulder sockets. They believe that to hit the "ground at the same place every time" the upper swing center (which they call the shoulder center) should remain in the same position throughout the swing - during the backswing, downswing and followthrough. In other words, they believe that a golfer should not allow the upper swing center to sway back away from its address location during the backswing, and then sway forward to its address location in the downswing - because they believe that it will lead to inconsistent ball contact (due to an inconsistent location of low point).

Is it logical to think of keeping the upper swing center stationary during the swing, and will it lead to a consistent low point location?

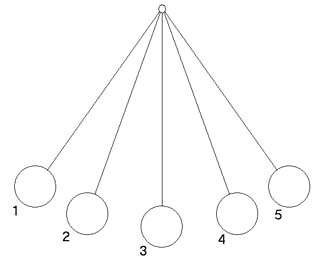

At first glance, this may appear to be true. Consider a pendulum of a grandfather clock.

Pendular arc of a grandfather clock

The pendulum of a grandfather clock consists of a single lever that is suspended from a "fixed" fulcrum point, and that fulcrum point doesn't move about in space. That fact allows the low point of the pendular arc (point 3) to always be located at the same spot (directly under the fulcrum point of the pendulum).A golf swing differs from a grandfather clock in the sense that a golfer has two arms that are suspended from the two shoulder sockets and there are two levers - the arms and the clubshaft. Many people think of the golf swing as being equivalent to a double pendulum swing model.

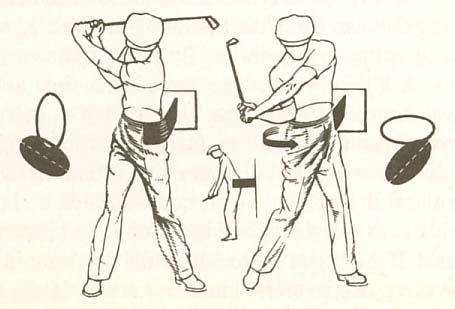

Double pendulum swing model

The double pendulum model is depicted on the left - and it consists of a central arm (equivalent to a golfer's arm) that is suspended from a "fixed" fulcrum point and a peripheral arm (equivalent to the clubshaft) that is attached to the central arm via a peripheral hinge joint (equivalent to a golfer's wrist). Low point will be located directly under the fulcrum point if the peripheral arm gets straight-in-line with central arm by low point.The golfer model (on the right) follows the same fundamental principle - except that there are two arms. The fulcrum point is the central hinge point midway between the two shoulder sockets (equivalent to the upper swing center in a golfer). Low point in this hypothetical golfer model would occur directly under the central hinge point (equivalent to the upper swing center) if two conditions are met - i) the two arms remain straight, and therefore have the same length, throughout the swing; and ii) the clubshaft is vertical at low point.

In a "real world" golf swing, all skilled golfers keep the left arm straight in the backswing and downswing. However, they allow the right arm to bend during the backswing and partially straighten during the downswing. At impact, the right arm will still be slightly bent, which means that low point cannot be located directly under the upper swing center (especially if the distance from the shoulder sockets to the ground is different for the left shoulder socket compared to the right shoulder socket). Consider an example of a golfer at impact.

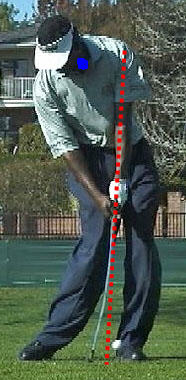

VJ Singh at impact - capture image from a swing video

The upper swing center is represented by the blue dot. At impact, the left arm is straight, the right arm is slightly bent and the clubshaft has forward shaft lean (clubhead end is lagging behing the grip end of the clubshaft). Also, note that the two shoulder sockets are not located the same distance from the ground at impact (as occurs in the simplistic double pendulum swing model golfer depicted above). The red dotted line represents the point-in-time when the clubshaft will be in a straight line relationship with the straight left arm and left shoulder socket and that occurs soon after impact. Low point will occur at that time-point, which means that low point is located under the left shoulder socket, and not under the upper swing center.Does that mean that there is no advantage to keeping the upper swing center stationary throughout the swing?

Not necessarily!

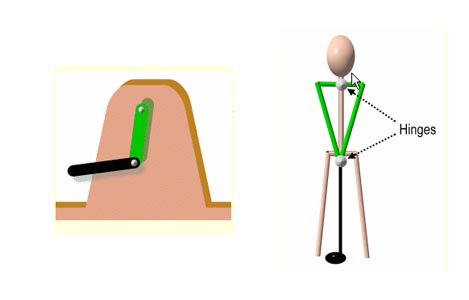

Consider the Pingman machine - an example of a golf club testing machine that is based on the double pendulum swing model.

PingMan machine in action - capture images from a swing video

Image 1 shows that the PingMan machine consists of a single central arm (equivalent to the left arm of a golfer) that is attached to a short lever at its central end via a central hinge joint (equivalent to the left shoulder socket of a golfer). The short lever (conceptually equivalent to the left clavicle that connects the left shoulder socket to the upper swing center) has a fixed length, and it is attached to the central fulcrum point (conceptually equivalent to the upper swing center). The motor that torques the central arm is located directly beneath the central fulcrum point and it causes the central hinge point assembly to rotate around the "fixed" central fulcrum point. In other words, the central fulcrum point (conceptually equivalent to the upper swing center) remains "fixed" in space throughout the swing. That fact ensures that low point always occurs at the same location swing-after-swing - low point will always be located under the central hinge point (equivalent to the left shoulder socket) if the central arm (equivalent to the left arm) and the clubshaft are in a straight-line relationship at low point.

The PingMan machine can produce a consistent low point location because its central fulcrum point (conceptually equivalent to the upper swing center) doesn't move in space and it remains "fixed" in space throughout the entire swing (backswing, downswing, and followthrough). I, therefore, believe that Bennett/Plummer's idea of keeping the upper swing center "fixed" in space throughout the swing makes a lot of sense from a *geometrical/mechanical perspective.

(* My primary objection to their S&T swing model, where Bennett/Plummer recommend that a golfer keep the upper swing center stationary throughout the swing, is based on a biomechanical argument - I believe that it is not possible to keep the upper swing center stationary using biomechanically natural movements. I believe that it requires biomechanically unnatural movements to keep the upper swing center stationary throughout the swing, and I believe that these biomechanically unnatural movements can potentially cause chronic back problems [+/- chronic left knee problems] over the long-term - I will discuss this particular issue at great length later in this review paper).

Bennett/Plummer's S&T swing biomechanics - required to keep the upper swing center stationary throughout the swing:

In this section, I am going to explain how Bennett/Plummer describe their S&T swing in their book [1] - with a major emphasis on explaining how they ensure that the upper swing center remains stationary throughout the backswing, downswing and followthrough. I am not going to provide a thorough explanation - golfers who want to learn the S&T swing should buy Bennett/Plummer's book [1] and/or their DVDs. This review paper is only a critical scholarly review of the S&T swing, and I am only going to primarily describe the fundamental movements that are required to keep the upper swing center stationary throughout the swing.Starting at address, Bennett/Plummer want a S&T golfer to have at least 55% of the weight over the left leg (and even up to 70% for beginner golfers). They want the upper swing center (midway between the shoulders) to be stacked over the lower swing center (midway between the hip joints).

S&T golfer at address - from reference number [1]

Note how the upper body is stacked vertically over the lower body, so that the spine is vertical at address.During the backswing, a S&T golfer must ensure that the upper swing center remains in the same position, and that it doesn't sway to the right (as occurs in a conventional swing where a golfer has rightwards spinal tilt at address). To achieve that goal, a S&T golfer needs to both extend the spine and tilt the spine 30 degrees to the left while performing the backswing pivot action. Bennett/Plummer use the following series of photographs to make that point.

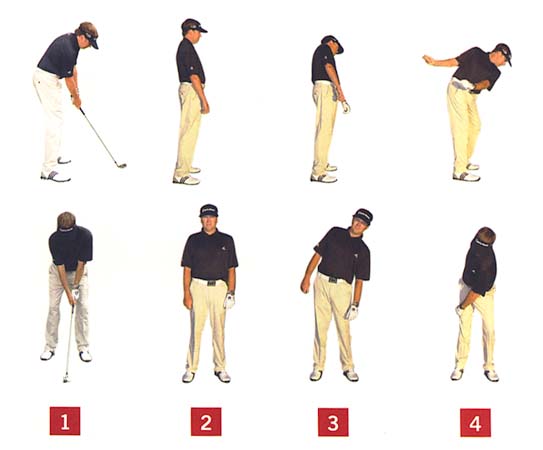

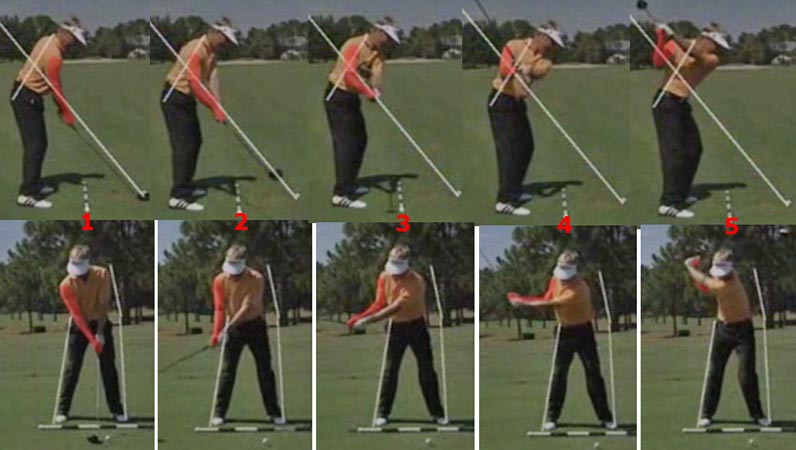

S&T backswing movements - from reference number [1]

Image 1 shows a S&T golfer at address.To get the "correct" feeling involved in performing a S&T backswing pivot action, Bennett/Plummer state that a golfer should stand erect and extend the spine (image 2), then tilt the extended spine 30 degrees to the left (image 3) and then bend forward at the waist (image 4).

Image 4 represents the end-backswing position, and to acquire that end-backswing S&T posture (where the upper swing center remains stationary relative to its address location), Bennett/Plummer state that a S&T golfer should also straighten the right leg. If the right leg straightens, it lifts up the right side of the pelvis by a few inches, and that makes it biomechanically easier to extend/tilt the spine to the left - as seen in image 4. This right leg straightening maneuver also prevents any weight shift to the right during the backswing.

Note that the pelvis/upper torso doesn't sway to the right during the backswing, and therefore there is no weight shift to the right (as would occur in a conventional golf swing if the golfer deliberately transfers his weight over to the right foot). At the end-backswing position, a S&T golfer still has most of his weight over the left leg (image 4).

Another important feature of the S&T backswing is that the shoulders turn much more vertically (compared to the conventional swing) - the left shoulder drops downwards more during the upper torso rotation. To prevent excessive left shoulder dipping, Bennett/Plummer accentuate the fact that the golfer must extend the spine while tilting it leftwards during the backswing pivot action. On page 56, they write-: "The spine must rise up out of its address tilt toward the ball. To understand this, look at it this way: If you only tilted to the left and turned your shoulders, your head would move down, changing your distance from the ball. So as you tilt to the left, you must also fully stretch your spine, from tilted forward to vertical. ---- Yes, this sounds complicated, but we see amateurs incorporating these spine actions very quickly. Why are they necessary? They constitute the only way you can turn back while keeping your shoulder center in place, which is the number one key to making solid contact with the ball."

To provide an idea as to how much left-leaning a S&T golfer should have at the end-backswing position, Bennett/Plummer use the following photographic diagram.

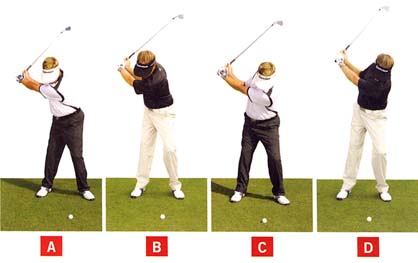

End-backswing postural variations - from reference number [1]

Photographs A and B show a rightwards-leaning posture, while photographs C and D show a leftwards-leaning posture. Photograph C represents the left-leaning posture that Bennett/Plummer specifically recommend.Although their recommended S&T posture is not excessively left-leaning (as demonstrated in photograph D), it still represents what I call a *leftwards-centered backswing pivot action.

(* I discussed the differences between a rightwards-centralised backswing pivot action [image B] and a leftwards-centralised backswing pivot action [image C] in my Optimal Weight Shift in the Full Golf Swing review paper).

I regard any leftwards-centralised backswing pivot action, where the golfer leans leftwards at the end-backswing position, as being equivalent to adopting a reverse pivoting end-backswing posture. Bennett/Plummer are obviously sensitive to any criticism of their S&T swing as being a reverse-pivoting swing style, and they discuss the issue of reverse pivoting on page 33 of their book [1]. On page 33 there is a box containing the following statements.

"FAQ: Isn't Stack and Tilt a reverse pivot?

That depends on how you define a reverse pivot. To us it means shifting to the front foot on the backswing and then to the backfoot on the downswing. This is certainly not what we teach. It is true in our model any weight shift on the backswing is to the front foot, but on the way down no weight ever moves to the back foot. So while the first part of the swing might look like the start of a reverse pivot, the move from the top is an aggressive forward shift. There is nothing reverse about that."

Note how Bennett/Plummer solve the leftwards-leaning posture that exists at the end of a S&T backswing - they recommend an "aggressive forward shift". What body part neeeds to shift forwards in an aggressive manner?

First of all, note the posture of the golfer in image B, who is using a rightwards-centralised backswing action. Note that he has a reverse-K posture at the end-backswing position - he has a rightwards-tilted spine and he has "space" under his right shoulder, in the region of the front of the right hip. The presence of that "space" allows him to drop his intact power package into that "space" below the right shoulder without any need for an aggressive left-lateral shift of the pelvis at the start of the downswing.

Here is a series of photos showing how Ben Hogan moves the intact power package (consisting of the left arm flying wedge [yellow], right forearm flying wedge [red], and right upper arm [green]) into that "space" during the early downswing.

Ben Hogan "slotting" his clubshaft - capture images from a swing video

I discussed the issue of "slotting" the club, via the biomechanical mechanism of moving the intact power package into the "space" under the right shoulder (and in front of the right hip), in my Book Review: The Slot Swing - Jim McLean review paper.

Note that the S&T golfer in image C (above) has no "space" under his right shoulder because his right hip is jutting-out to the right due to the straightening of the right leg in the backswing, which uptilts the right pelvis. That biomechanical fact requires an aggressive left-lateral shift of the pelvis at the start of the downswing - to both "convert" a leftwards-tilted spine (in the early downswing) into a vertically-oriented spine (in the mid-downswing) and finally into a rightwards-tilted spine (by impact), and to create "space" for the right elbow in the mid-downswing. An aggressive left-lateral shift of the pelvis at the start of the downswing is a key feature of the S&T swing. Let's consider how Bennett/Plummer describe this critical move in their book [1].

Bennett/Plummer discuss the downswing in chapter 4 of their book [1].

On page 73, they state-: "To start the hips and legs correctly on the downswing, you must immediately lean into your left leg. This shifts more weight to your front side and starts your hips moving to the target. --- As your hips continue to move forwards, your left hip gets higher than the right - the opposite of the backswing - and your left leg starts to straighten. ----- When your left arm reaches parallel to the ground on the downswing (halfway down), your hips have slid about an inch torward the target compared to the top of the backswing, putting your weight 70/30 on your left side. Your left knee has moved an inch in front of the left ankle as a result of the lateral motion."

In other words, by the end of the early downswing (defined as the time-point when the left arm is parallel to the ground), a S&T golfer should have moved his pelvis and left knee about an inch left-laterally towards the target. This left-lateral movement continues in the mid-downswing, and when the club reaches the delivery position (point where the clubshaft is at the 3rd parallel and parallel to the ground), Bennett/Plummer state-: "your hips have moved another inch toward the target, and your left knee is now two inches in front of your left ankle. Your weight is now 80/20 on the left."

Bennett/Plummer recommend that the aggressive left-lateral sliding motion of the pelvis continue through the late downswing and followthrough. They write-: "At impact, your hips have shifted another inch toward the target, with 90% of your weight on the left side. And by the time your right arm is parallel to the ground after impact (halfway through) your weight is 95/5 and the lateral hip slide is complete".

Hopefully, readers can now understand why Bennett/Plummer state that they recommend an "aggressive forward shift" in their S&T downswing action. On page 73, they state-: "The popular advice to make a slight "bump" toward the target with the hips does not transfer enough weight to the left side soon enough or for long enough."

Bennett/Plummer not only recommend a left-lateral pelvis sliding motion - they also want a S&T golfer to experience a "jumping up" phenomenon during the left-lateral pelvis sliding motion. On page 75, they write-: "To level out your hips, you need to push up with your legs, as if you were launching yourself off the ground. Imagine a shot putter on the release or a tennis player serving: They literally jump off the ground". ----- The upward thrust of the lower body is another trademark move of Stack and Tilt. This jumping up should start when the club approaches impact (technically, when it reaches parallel to the ground on the downswing). Our experience is that better players often make the move instinctively, because the club is dropping and gaining dynamic weight. To "lighten" the club and avoid a crash into the ground, the good player will push up with his legs as the club nears impact. Less-experienced golfers have to consciously "jump" to deliver the club correctly. Along with the feeling of jumping up, another helpful image, as we've discussed, is tucking the butt under the torso through impact. As the legs straighten and push up, the muscles in your rear end should push towards the target, moving the hip center further forward. This shifts your hips as far as they can go and raises your belt-line three to four inches higher than it was at address, with your tailbone over the inside of your left foot from the face-on view".

Therefore, to mentally picture a S&T golfer's downswing action (based on Bennett/Plummer's description), you need to mentally picture how the S&T golfer aggressively shifts his pelvis left-laterally (incorporating a "tucking the butt under the torso" pelvic action) and how he also thrusts up with his legs in the late downswing to reverse his pelvic tilt (from being downwards tilted at the end-backswing position to being upwards tilted at impact).

Here is swing video of a S&T golfer - Troy Matteson - who employs an assertive left-lateral pelvic thrust action and a "jumping-up" phenomenon at impact.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zzhmPqXoljY

What "effect" do these dual biomechanical actions have on the golfer's spine?

Bennett/Plummmer describe the spine movements on page 78 of their book [1]. They state-: "On the backswing your spine tilted 35 degrees to the left (which became your forward tilt to the ball) and stretched out as far as possible. The purpose of these spine actions is to let the upper body turn back without the shoulder center moving off the ball. Coming down, the spine must reverse these positions, with the goal being to keep the shoulder center in place. If you're getting the feeling that a fixed shoulder center is the biggest priority in the swing, then you're starting to understand Stack and Tilt. --- To reverse the backswing actions, your spine must start to tilt to the right immediately from the top. The lateral sliding of the hips in conjunction with the unwinding of the shoulders is what allows that to happen: When your hips shift forward and your shoulder center stays, the spine will tilt to the right. When you get halfway down, your spine should be vertical from the face-on view, as it was at address. By impact, your spine should be tilted away from the target, the exact amount depending on how much you shift your hips forward - the wider the stance (and the longer the club), the more the hips slide. --- Your spine will continue to tilt farther and farther away from the target until your right arm parallels the ground after impact, when the hips slide is complete".

The i) aggressive left-lateral pelvic sliding action, the ii) "butt thrusting under the lower torso" action, and the iii) aggressive "jumping up" action of the legs needed to reverse the spine tilt and keep the shoulder center (upper swing center) in place during the downswing/followthrough is very characteristic of the S&T swing.

Here is a S&T instructor demonstrating a drill that shows how one has to aggressively thrust the pelvis forward while keeping the shoulder center (upper swing center) back.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F0qw0r7pDQU

Note how much the lower body moves laterally forward in the downswing and followthrough, while the upper body is kept back.

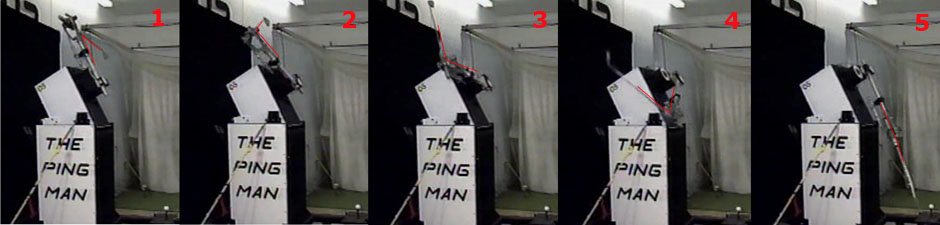

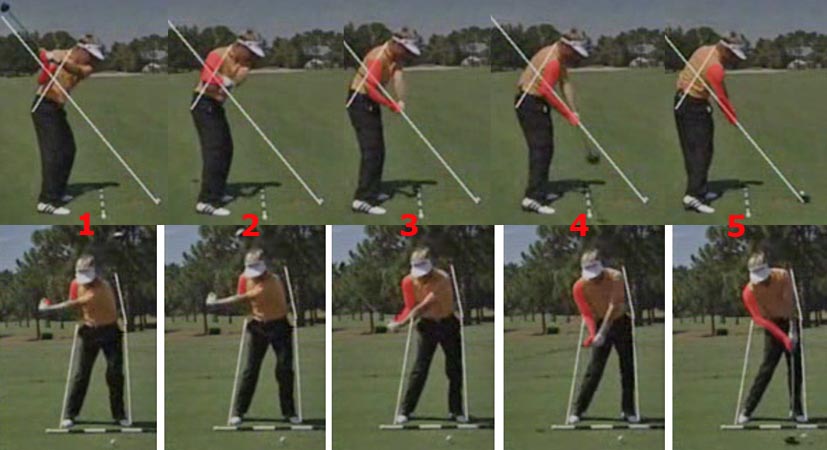

Lower body and spine movements in the S&T downswing - adapted from reference number [1]

Consider the movements of the lower body and spine in the S&T swing.Image 1 shows a S&T golfer at the end-backswing position. The pink arrowed line shows that the shoulder center (upper swing center) is vertically over the ball. Note that the upper torso has leftwards-tilt and note that the right pelvis is higher than the left pelvis.

Image 2 shows a S&T golfer in the early followthrough (immediately post-impact). Note that he has kept the shoulder center (upper swing center) stationary - the pink arrowed line hasn't moved (relative to the left foot and ball position). Note that the pelvis has shifted far to the left - note that the outer border of the left pelvis is a few inches outside the outer border of the left foot. Also, note that the left pelvis is now a few inches higher than the right pelvis.

Image 3 - I used the Adobe Photoshop program to make image 2 proportionately smaller in size, so that I could superimpose image 2 over image 1 to produce a composite image (consisting of image 1 and image 2). This composite image gives one a good impression of how much the lower body moves in a S&T downswing. The blue dot represents the shoulder center (upper swing center) and one can see that it essentially remains stationary during the downswing. The green dotted line shows the upper torso tilt angle at the end-backswing position, and the red dotted line shows the upper torso tilt angle immediately post-impact. The change in upper torso tilt angle, and therefore spine tilt angle (as seen from face-on) is due to the aggressive left-lateral pelvic shift motion - represented by the curved orange arrowed line. I made the orange arrowed line curved to show that the pelvis not only moves left-laterally - the pelvis also changes its tilt-angle from being right-uptilted at the start of the downswing (solid green line) to being left-uptilted (solid red line) at impact.

The key point that a golfer needs to understand about the S&T downswing is that the majority of the left-laterally directed spine movement occurs at the level of the lower spine (lumbar spine) and not at the level of the mid-upper thoracic spine (as occurs in the traditional/conventional swing). That biomechanical fact is the major reason why I would never recommend the S&T swing to a young golfer. There is no doubt in my mind that the S&T swing can work well from a geometrical/mechanical perspective, but I believe that the required biomechanical movements occurring at the level of the lumbar spine are not natural, and I believe that they are likely to predispose to chronic back problems over the long-term (40-60 year time period). What is the basis for my belief that an aggressive lateral thrusting movement occurring at the level of the lumbar spine is not biomechanically natural?

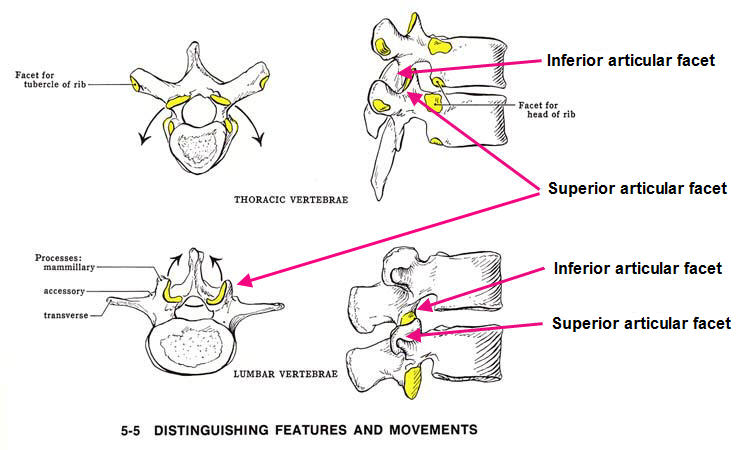

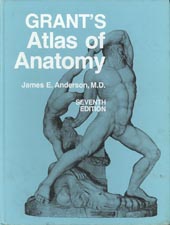

Consider the anatomy of the thoracic and lumbar vertebrae.

Anatomy and movements of the thoracic and lumbar articular (facet) joints - from reference number [3]

Starting with the thoracic vertebra, note that each thoracic vertebra has a superior (top) articular facet and an inferior (lower) articular facet - colored in yellow. That allows each thoracic vertebra to articulate with the neighbouring thoracic vertebra just above, and just below, that particular thoracic vertebra. The surface of both the superior and inferior articular facet is flat, and the inferior articular facet of one thoracic vertebra lies over the superior articular facet of the neighbouring thoracic vertebra - like shingles on a roof. That allows the inferior articular facet of one thoracic vertebra to rotate-slide over the superior articular facet of the thoracic vertebra (just below), and this rotary-slide movement (involving multiple thoracic vertebrae) will cause a latriflexion of the thoracic spine from side-to-side. That movement allows a person to rotate the upper torso around the latriflexing thoracic spine in a biomechanically natural manner.Note that each lumbar vertebra also has a superior and inferior articulating facet - colored in yellow. The superior articular facet is cup-shaped and it has elevated bony side-ridges on the lateral (outer) side that are responsible for its cup-shaped appearance. The inferior articular facet is dome-shaped, and that allows the inferior articular facet to move in a saggital (vertical) plane within the cup-shaped confines of the superior articular facet. The anatomical structure of the lumbar spine's articular facet joints allows a person to flex-extend the spine in a saggital plane, but resists any latriflexion (rotary movements) of the lumbar spine from side-to-side.

In a S&T downswing action, the aggressive left-lateral thrusting motion of the pelvis (combined with the pelvic tilting phenomenon) forces the lumbar spine to latriflex during the downswing - even though the lumbar vertebra are not anatomically designed for that type of side-to-side latriflexion motion. Over many years of undergoing this type of biomechanically unnatural movement, that abnormal type of repetitive stress is likely to progressively damage the lumbar articular facet joints and predispose to lumbar articular facet joint osteoarthritis. As the lumbar articular facet joints become progressively damaged and osteoarthritic, they will no longer be able to resist any latriflexion motion. That will increase the degree of latriflexion motion occurring at the level of each lumbar articular facet joint during a S&T downswing action. This increased degree of latriflexion movement at the level of each lumbar vertebral segment is going to abnormally stress the intervertebral discs that are situated between the lumbar vertebra.

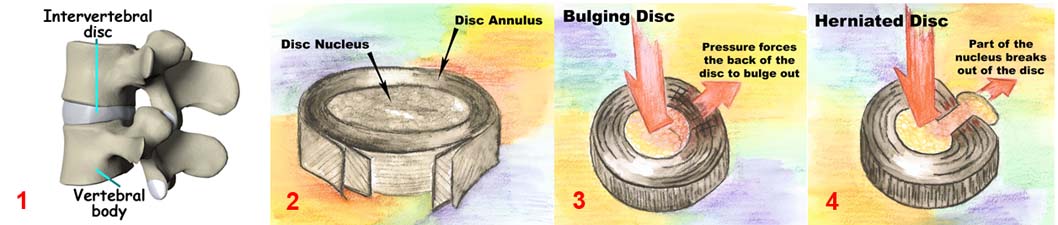

Degenerative lumbar disc disease - a diagrammatic representation

Image 1 shows that an intervertebral disc separates each lumbar vertebra from the neighbouring lumbar vertebra.Image 2 show that each lumbar intervertebral disc consist of two parts. The central part is called the nucleus pulposus and it consists of a gelatinous material, that acts as shock-absorber when the lumbar spine is subjected to a vertical stress (eg. when lifting heavy rocks). The disc nucleus is surrounded by the disc annulus (annulus fibrosis) which consist of concentric layers of a strong fibrous material. A healthy disc annulus confines the disc nucleus within the center of the intervertebral disc.

If a lumbar intervertebral disc is subjected to many years of a repetitive latriflexion stress that asymmetrically compresses the intervertebral disc, then the annulus fibrosis may progressively degenerate and this will result in degenerative lumbar disc disease. Small tears may occur within the structure of the degenerating disc annulus, and if the tears join to form large defects in the disc annulus, then any repetitive vertical (or asymmetric compressive) stress can force the disc nucleus to bulge-out through that "defect" in the degenerated disc area (image 3). If the nucleus bulges-out beyond the confines of the disc annulus ring, then the condition of a herniated lumbar disc exists (image 4). Lumbar disc herniation is a common back problem, and I suspect that the latriflexion stress associated with a S&T downswing action may increase a S&T golfer's likelihood of developing degenerative lumbar disc disease, and a lumbar disc herniation problem, after many years of repetitive excessive latriflexion stress.

There is another orthopedic problem that may plague S&T golfers after many years of performing the S&T swing - left knee joint osteoarthritis.

The knee joint is designed for a flexion-extension type of movement. The knee joint has internal/external knee ligaments that prevent the knee from moving sideways - either laterally (outwards) or medially (inwards). If these ligaments become abnormally stretched due to forces that apply an excessive sideways force to the knee, then the knee joint cartilage lining the bony surface of the knee joint (lower surface of the femur and upper surface of the tibia) can become progressively damaged. That can eventually lead to knee joint osteoarthritis.

In the S&T swing, the S&T golfer already has most of his weight over the left leg at the end-backswing position and his pelvis is already shifted to the left. During the downswing, the pelvis and left knee shift even more leftwards - see Bennett/Plummer's description of the pelvis/left knee movement in the S&T downswing (that I previously quoted). Here is a photograph of a S&T golfer in the early followthrough.

S&T golfer in the early followthrough - from reference number [1]

Note that the outer border of the pelvis, and the outer border of the left knee, is outside the outer border of the left ankle - the red lines drawn parallel to the left thigh and left leg demonstrate that the left knee joint is angled laterally, and both red lines are outside the outer border of the left ankle joint. I believe that the left knee joint is being abnormally stressed by being forced into that position as a result of an aggressive left-lateral pelvis shift motion, and I suspect that this type of repetitive stress may eventually lead to left knee joint osteoarthritis.I believe that it is biomechanically safer to always keep the outer border of the left pelvis inside the left foot at impact, so that the left knee is not being subjected to an excessive sideways-directed stress force.

Here is a photograph of Ben Hogan nearing impact.

Ben Hogan near-impact - from reference number [4]

Note that the outer border of Ben Hogan's left pelvis is well within the vertical boundary of his left inner foot, and he is bracing his left leg/knee. By bracing the left leg/knee for impact, a golfer is preventing the left knee from being subjected to an excessive sideways force that over-stretches the external ligaments on the lateral (outer) side of the left knee joint. I think this type of pelvis/left knee alignment at impact is less likely to predispose to left knee joint damage over the long term.

Swing biomechanics of the traditional/conventional swing

In their book [1], Bennett/Plummer liken the torso movement of a S&T golfer to the torso movement of other sport performers - a tennis player performing an overhand serve, a shot putter, and a high jumper performing a Fosbury flop-style of high jump action. I can understand why they chose those types of sport actions to compare to their S&T swing.

I believe - from the perspective of biomechanically natural movements - that a golfer's torso movement should be a rotational motion, and that most of the upper torso's rotational movement should occur at the level of the thoracic spine, and not at the level of the lumbar spine. Sport actions demonstrating that the torso rotation is primarily rotational (and mainly involving the thoracic spine) include a tennis player hitting a forehanded (or back-handed) shot, a discus-throwing action, a baseball pitching action, a stone skipping action, a back-handed frisbee throw action, and a baseball third baseman throwing a ball sidearm/underhanded to the first baseman.

An excellent demonstration of the rotational quality of the lower torso (pelvic) and upper torso (shoulder) movements in a golf swing can be seen in this Ben Hogan swing video.

Ben Hogan video - http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_AmPuzgBXEM

The swing video comes from an Ed Sullivan TV show, and it features Ben Hogan in a comedy act. Although Ben Hogan is joking with the TV show audience in this video piece, it is very informative to watch his torso movements during his swing action. Note how his lower torso (pelvis) and upper torso (shoulders) primarily rotate in a horizontal plane in his swing action. There is no sense that Ben Hogan is forcing his torso to move in a ferris-wheel manner, rather than a merry-go-round manner. I believe that Hogan's spinal movements are biomechanically natural, and I believe that he is not subjecting his lumbar spine to biomechanically stressful latriflexion forces.

In his book [5], Ben Hogan described the downswing pelvic action as a rotational action. He used the following diagram to demonstrate his position.

Hogan's elastic band idea - from reference number [5]

Ben Hogan stated that a golfer should think of an elastic band stretching from the front of his left pelvis to an attachment point on a wall behind the golfer, where the attachment point is directly behind the left hip. In the backswing, the elastic band will become stretched when the left pelvis moves forward (towards the ball-target line). Then the elastic band will snap back at the start of the downswing thus causing the left pelvis to be pulled back towards the tush line (left hip clearing action). That downswing pelvic motion is a rotation of the left pelvis back towards the tush line, and it is not primarily a left-lateral pelvic slide action. There is only a small amount of left-lateral pelvic motion required during the left hip clearing action - and that is the amount needed to re-weight, and brace, the left leg. In Hogan's swing, he only moves the pelvis about 2-3" left-laterally during his pelvic rotational motion.Consider the following slow-motion video of Hogan's swing - http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QL_6M_xZvq0

Here are two capture images from that swing video.

Hogan downswing action - capture image from his swing video

In the first image, Ben Hogan is at his end-backswing position. A pink arrowed vertical line drawn from the outer border of his waist (at belt level) passes just behind the inner boundary of his left heel.In the second image, Ben Hogan is at the end of his early downswing. Note how he has re-weighted and braced his left leg. Note that the pink-arrowed vertical line drawn from the outer border of his waist (at belt level) passes about 1-2" in front of the inner border of his left heel. The amount of left-lateral pelvic motion is very small and it is often referred to as a "hip bump". The primary pelvic motion is a rotary motion - note that Hogan has rotated his pelvis about 45 degrees during the early downswing - by pulling his left buttock back towards the tush line.

I think that the golfer who best demonstrates this Hogan-style rotary pelvic motion is Jamie Sadlowski - the current (2008/9) world long-drive champion. His pelvic motion is a "pure" rotational motion, and there is no left-lateral pelvic slide action at the start of his downswing.

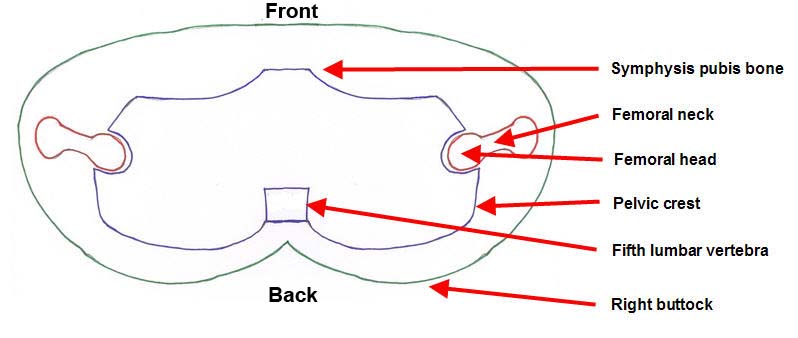

First consider this cross-sectional diagram of the human pelvis, so that you can better understand his pelvic motion in the next composite photo showing Jamie Sadlowski's backswing/downswing action.

Diagram showing a cross-sectional view of the the pelvis at the level of the hip joints

Now consider Jamie Sadlowski's backswing/downswing pelvic motion (where I have combined the same diagram with photos of Jamie Sadlowski during his swing action).

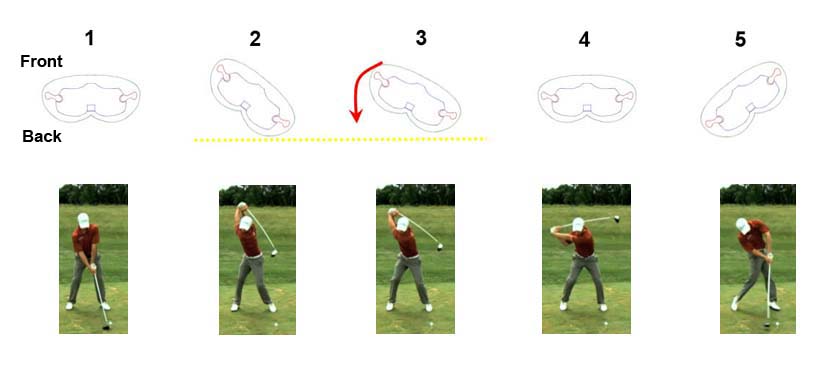

Jamie Sadlowski's pelvic movements during the backswing and downswing - capture images from his swing video [6]

Image 1 shows Jamie Sadlowski at address - his pelvis is square to the ball-target line (parallel to the ball-target line) and his pelvis is centralised between his feet.Image 2 shows Jamie Sadlowski at his end-backswing position. Note that there has been no swaying of the pelvis to the right. He has simply pulled his right buttocks back away from the ball-target line in the direction of the tush line (yellow dotted line) and during this pivot action the left buttocks moves leftwards as well as backwards (towards the tush line).

Image 3 shows Jamie Sadlowski's first pelvic motion at the start of the downswing. Note that he is performing Hogan's "elastic band" pelvic action - he is pulling his left pelvis back towards the tush line (see red curved arrow in diagram number 3). Note that there is no breaking-in of the right knee and there is no left-lateral swaying of the pelvis.

Image 4 shows Jamie Sadlowski at the end of his early downswing (when his left arm is parallel to the ground). Note that his pelvis is square - parallel to the ball-target line (as at address). Note that his pelvis is still centralised between his feet - there has been no left lateral pelvic shift movement. Note that his right knee has still not broken-in, and it is unchanged compared to his end-backswing position. This represents the hip-squaring phase of his downswing, and he has the characteristic Sam Snead "sit-down" look - with both knees bowed slightly outwards.

Image 5 shows Jamie Sadlowski at impact. Note that his pelvis is still centralised between his feet - there has been no left-lateral shift of his pelvis towards the target during his entire downswing. Note that his pelvis is open to the target. Note that his right knee has finally broken-in during the late downswing, and that biomechanical phenomenon is secondary to the fact that his pelvis has rotated to an open position and also due to the fact that his right leg is now significantly unweighted.

Note how Jamie Sadlowski's pelvis remains horizontal throughout the entire downswing - there is no right uptilting of the pelvis at the end-backswing and no left-uptilting of the left pelvis at impact, as occurs in the S&T swing.

Now consider the rotational movement of Jamie Sadlowski's upper torso.

Jamie Sadlowski's early downswing - capture images from his swing video [6]

Image 1 shows Jamie Sadlowski at the end-backswing position - his upper torso has rotated much more than his lower torso. However, note that most of his upper torso rotation involves the mid-upper thoracic spine area above the level of his navel (umbilicus). There is virtually no torquing-rotation of the lumbar spine area of his upper torso, and his lumbar spine has rotated only as much as the pelvis during his backswing action.During his early downswing, his pelvis and lumbar spine rotate to the same degree in a horizontal manner, and by the end of the early downswing (image 5) his pelvis and lumbar spine have rotated about 45 degrees. The fact that the pelvis and lumbar spine are rotating by the same amount, means that the lumbar spine is not being subjected to an excessive rotational torque-force. His upper torso (shoulder area) is also rotating near-horizontally, and that rotational movement is occurring at the level of the thoracic spine. There are no biomechanically unnatural latriflexion forces in play with respect to his lumbar spine - as occurs in a S&T swing - and the only torsional forces in play with respect to the spine (thoracic and lumbar spine) are natural rotational forces.

I believe that this type of torso rotational movement is biomechanically natural and unlikely to lead to chronic back problems.

A key feature of Ben Hogan's and Jamie Sadlowski' swing, that allows them to avoid having any latriflexion forces stress the lumbar spine, is the fact that they have a rightwards tilted spine throughout their entire backswing and entire downswing - there is no time-point during their backswing/downswing when their spine is tilted to the left. Therefore, there is no need for an aggressive left-lateral pelvic slide motion to reverse any leftwards spine tilt during the downswing (as required in the S&T swing).

Comparison between Bennett/Plummer's perception, and my personal perception, of the traditional/conventional swing.

In their book [1] Bennett/Plummer have a chapter (chapter 5) where they compare their S&T swing to the traditional/conventional swing. I personally think that they have grossly misrepresented many features of the traditional/conventional swing in that chapter, and I will offer this website's visitors a different perspective of the traditional/conventional swing (as comprehensively detailed in my many review papers relating to the modern, total body golf swing).

I am going to reproduce Bennett/Plummer's book statements regarding the traditional/conventional swing in complete (unedited) detail, so that I cannot be incorrectly accused of unfair/selective editing of their book's material. To differentiate their comments from mine, I will use an Arial font for their book's unedited statements, and the standard Times Roman font for my personal comments. I will not reproduce their book's statements on the S&T swing, because I am not contesting the accuracy of their description of their S&T swing.

Starting with address.

Address

Side tiltThe spine is tilted away from the target, with the right shoulder down, positioning the head behind the ball. This presets a shift to the right on the backswing, which requires a return shift to the left in time for impact to avoid bottoming out behind the ball.

My comment: It is true that a traditional golfer has rightwards spinal tilt at address, and that the right shoulder is lower than the left shoulder. However, that doesn't automatically preset a shift to the right on the backswing - in terms of a lateral-swaying movement. I believe that a traditional golfer should simply rotate around his rightwards-tilted spine without any lateral shift of the lower body or upper body to the right. I believe that any swaying to the right is disadvantageous and that it is not obligatory in a traditional/conventional swing.

Weight distribution

With the hips and shoulders tilted away from the target, more weight is on the back foot, which encourages a shift off the ball on the takeaway.

My comment: I do not believe that the pelvis has to be moved/tilted away from the target at address. Some traditional golfers have their pelvis centralised at address, and with a rightwards tilted spine, they will have slightly more weight on the right foot at address. However, some traditional golfers have their pelvis moved slightly over to the left at address, so that their combined weight (pelvis and upper torso combined) will be more equally balanced between the feet.

Shaft position

The grip end of the club is pulled back so that it points between the arms.

My comment: When the grip end of the club is centered between the arms, that position is called the adjusted address position (in TGM terminology). Most traditional golfers, who are swingers, prefer to start off with the club in that central position.

Stance

The center of the hips is set over the back half of the stance, well behind the ball.

My comment: This statement is not true. Only a minority of traditional golfers adopt this practice. The majority of traditional golfers have their pelvis either centralised or left-centralised. I favor left-centralised, and I discussed this issue in detail in my Left Arm Swinging, Right Arm Swinging and Hitting review paper.

Posture

The spine is straight and the shoulders are pulled back (down target view). The golfer must view the ball out of the bottoms of his eyes, which is awkward, and the stiff, unnatural back and shoulder positions restrict range of motion.

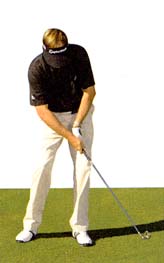

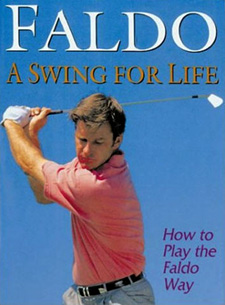

My comment: This rigidly unnatural posture (as described by Bennett/Plummer) is definitely not recommended in the traditional golf swing. In my Address, Setup and Alignment chapter, I used the following photograph of Nick Faldo as a role model.

Nick Faldo at address - from reference number [7]

Note that only his mid-lower spine is straight. His upper thoracic spine is bowed slightly forward, and his shoulders are rounded. His cervical spine is in sympathetic alignment with his upper thoracic spine, and that allows him to look straight down at the ball, without having to look "out of the bottoms of his eyes".

Takeaway

Hand pathThe hands and arms extend the club straight back away from the ball, keeping the club in front of the body and pulling the right arm immediately off the chest.

My comment: Some traditional golfers, who use an one-piece takeaway, adopt this "incorrect" practice of trying to take the clubhead straight back away from the ball, and they attempt to artificially keep the clubhead traveling back along the ball-target line. However, this "incorrect" practice is definitely not routinely recommended. I favor the right forearm takeaway (and not the one-piece takeaway) for the traditional swing, and I used the following photograph to demonstrate the "correct" takeaway in my How to Move the Arms, Wrists and Hands in the Golf Swing review paper.

Stuart Appleby's takeaway - capture images from his swing video [8]

Stuart Appleby uses the right forearm takeaway and that causes his right forearm (blue line) to move back along the surface of the inclined plane (parallel to the inclined plane) during the early takeaway. That right arm/forearm/hand motion, in turn, ensures that the clubhead immediately moves away from the ball-target line. The peripheral end of the clubshaft points at the ball-target line (red arrow), but the clubhead does not remain on the ball-target line in the early takeaway.The right arm must separate slightly away from the right side of the torso during either the right forearm takeaway, or the one-piece takeaway - because the left shoulder is simultaneously moving down-and-to-the-right. If the left shoulder moves rightwards, and the left arm remains straight, then the slightly bent right arm must move away from the right side of the torso to maintain a constant amount of extensor action. I discussed the issue of extensor action in my How to Power the Golf Swing review paper.

Shoulder turn

The left shoulder begins to turn level, lifting the shoulders off the downward angle established at address.

My comment: I believe that the shoulders should turn perpendicularly around the rightwards tilted spine during the traditional takeaway. That motion doesn't cause the shoulders to lift off the "downward angle established at address". Note that Stuart Appleby's left shoulder is slightly down-tilted in the above photo, and that the shoulder turn angle is not perfectly level to the ground.

Wrists Hinge

The wrists have not started hinging because the spine is not tilting to the left. The club stays low for the first few feet.

My comment: I cannot understand why Bennett/Plummer believe that there is causal connection between a "hinging of the wrists" action and the degree of left spine tilting during the takeaway. I believe that the major causal factor causing the left wrist to cock upwards (and the right wrist to dorsiflex backwards) during the backswing is the bending of the right elbow - and one would not expect the right elbow to start bending much during the takeaway.

If the club stays too low during the first few feet of the takeaway in the traditional swing, then the most likely explanation is that the golfer is "incorrectly" moving his arms/club away from the torso in a downwards-direction and/or he is allowing his left shoulder to dip down towards the ground during the takeaway and/or he is "artificially" keeping his two arms rigidly straight. Note in the Stuart Appleby photo (above) that the clubhead does not stay low to the ground during the takeaway.

Ascent of the hands

The hands move level to the ground, the old "low-and-slow takeaway".

My comment: I have already addressed this issue in my above comment. Note that Stuart Appleby does not move his hands level to the ground in the takeaway - see photo above. His hands automatically move inside-and-upwards as a result of employing a right forearm takeaway.

Halfway back (left arm parallel to the ground)The arms have run out of extension, so they start to lift the club off the circular arc, disconnecting the upper arms from the chest and pulling the right elbow farther away from the right side.

My comment: I have no idea how Bennett/Plummer can claim that a traditional golfer lifts his club off its circular arc during the mid-backswing. Consider the traditional/conventional swing of Stuart Appleby.

Stuart Appleby's backswing - capture images from his swing video [8]

You can see Stuart Appleby reaching the halfway back position in images 3 and image 4 - note that his right elbow is still very close to the right side of the torso. The distance of the right elbow/arm from the right side of the torso is "fixed" by the amount of extensor action needed to keep the left arm straight. Note that there are two factors that determine how far Stuart Appleby's right arm/elbow is going to be from the right side of the torso at the halfway point (image 4) - i) the length of his straight left arm under the influence of extensor action and ii) how far his left shoulder socket has moved rightwards at that time point in his backswing.Stuart Appleby is definitely not lifting his club off its circular arc.

Wrist hinge

The wrists have not hinged enough because the right elbow is pulling up and off the rib cage and the hands are not ascending.

My comment: I believe that the major factor causing the wrists to hinge (left wrist to upcock and right wrist to dorsiflex) during the backswing is the timing of the right elbow bending action. Stuart Appleby uses the right forearm takeaway and he therefore has a large amount of right elbow bending by the time he reaches the halfway back time-point (image 4 above). Traditional golfers who use the one-piece takeway keep their right elbow straighter in the mid-backswing and only bend their right elbow in the late backswing - they therefore hinge their wrists later.

The statement that the wrists have not hinged because "the hands are not ascending" is nonsensical, because if the left arm is parallel to the ground at the halfway back time-point then the hands must have ascended to the same level as the straight left arm, which is horizontal to the ground.

Shoulder center

As the body starts to rotate away from the target, the body's forward tilt is maintained and the top of the spine shifts to the right, moving the shoulder center off the ball.

My comment: Bennett/Plummer are correct - the shoulder center must move slightly off the ball if a traditional/conventional golfer rotates his upper torso around a rightwards tilted spine. However, its is amazing how little the shoulder center (upper swing center) moves in a rightwards-centralised backswing action.

Stuart Appleby has a rightwards-centralised backswing action - he simply rotates around his rightwards tilted spine without any swaying motions of either his lower torso or upper torso. Consider the movement of his upper swing center (shoulder center) during his backswing.

Stuart Appleby's backswing - capture images from his swing video [8]

Image 1 shows Stuart Appleby at address. I placed red lines alongside his head, a blue dot in the position of his upper swing center (shoulder center) and a yellow line depicts his rightwards-tilted spine.

Image 2 shows Stuart Appleby at his end-backswing position. His degree of rightwards spinal tilt (yellow line) is unchanged. Note how far his upper swing center (shoulder center) has moved away from that blue dot (which hasnt been altered from a positional perspective). It has probably only moved <2", which is a negligible amount.

Weight shift

With the body moving over the right leg, more weight shifts to the right foot.

My comment: Bennett/Plummer are correct. If a traditional/conventional golfer rotates his upper torso around a rightwards tilted spine, and the arms move over to the right side of the body, then there must be more weight over the right foot. However, it is not due to the body moving over the right leg - note that Stuart Appleby's upper torso always remains within the inner boundary of his right knee/foot, and no part of his torso moves over his right leg.

Top of backswing

Spine tiltThe spine has maintained most of its address tilt, so the upper body has turned behind the ball, moving the shoulder center several inches to the right. The shoulders have made a level turn.

My comment: Bennett/Plummer are correct. The shoulders turn relatively level in a traditional/conventional golf swing, and the shoulder center (upper swing center) must move slightly rightwards. However, if a traditional golfer uses a rightwards-centralised backswing action, then the amount of shift of the shoulder center (upper swing center) is very small - see photo of Stuart Appleby above.

Arm swing

Continuing on a vertical plane, the arms have nowhere to go but up. When they can't go any higher, they flex more and the wrist collapse and drop the club toward the head. The right arm also breaks down and flexes away from the body.

My comment: I consider Bennett/Plummer's statements to be incomprehensible. Consider Stuart Appleby's traditional/conventional swing.

Stuart Appleby's backswing - capture images from his swing video [8]

Image 5 shows Stuart Appleby at his end-backswing position. He is in a perfect end-backswing position - he has perfectly assembled his power package, and his right forearm flying wedge has the "desired" alignment relative to his left arm flying wedge. His left wrist is anatomically flat and there is no collapse of his left wrist. I cannot fathom how anybody could imagine that Stuart Appleby's "right arm has broken down" or that his "arms had nowhere to go but up".Leg action

The left knee moves inwards, toward the right, and the knees do not change from their address flex.

My comment: That statement about the "knees do not change their flex" is perfectly correct with respect to the right knee - see Stuart Appleby at his end-backswing position (image 5 above). However, the left knee must naturally bend more as it becomes progressively more unweighted during the backswing (as the pelvis rotates back about 45 degrees).

Hip turn

The hip rotation is severely limited because the right knee remains flexed. The hips are turning level, or the left hip is higher than the right.

My comment: In the traditional swing, maintaining right knee flex does limit hip rotation. Also, it is biomechanically natural for the pelvis to move horizontally in the traditional swing - if the golfer doesn't excessively straighten his right knee and uptilt the right pelvis. I have never seen traditional golfers get their left hip higher than the right hip at the end-backswing position.

Halfway down (left arm parallel to the ground)

Weight shiftAfter a small forward shift, if any, to start the downswing, the weight remains largely on the right foot, and the head is behind the ball.

My comment: I disagree that the weight would remain largely on the right foot at the end of the early downswing (defined as the time point when the left arm is parallel to the ground) in a traditional/conventional golf swing. A traditional golfer should have have already squared his pelvis by the end of the early downswing and achieved the "sit-down" look characteristic of a golfer who has achieved a hip-square position. In that hip-square position, the weight should be nearly equally-balanced between the two feet.

The head should always remain behind the ball throughout the entire downswing in a traditional swing.

Hip action

The hips, which have made a level turn going back, now reverse direction, spinning open, without making a significant lateral move toward the target.

My comment: It is true that a traditional golfer should not make a significant lateral move of the pelvis towards the target in the early downswing. There is only a small left-lateral "hip bump" at the start of the downswing as the golfer re-weights the left leg - and this small amount of lateral pelvic motion occurs while the left pelvis is being pulled back to the tush line. However, a traditional golfer should never spin the hips open - in terms of actively rotating the right pelvis outwards towards the ball-target line. The "correct" pelvic action was described by Ben Hogan in his "elastic band" idea - the left buttock is pulled back toward the tush line while the right buttock is still kept on the tush line. Shawn Clement described this Hogan-style pelvic action in his swing video lesson - http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NNwSfz0_KDM

Hand path

With the hips and shoulders turning and inadequate hip slide, the hands are pulled outside the correct downswing path. Good players compensate by standing up sooner to try and drop the shaft, but high-handicappers tend to hit pulls and slices.

My comment: When Bennett/Plummer state that the hands are "pulled outside the correct downswing path", they are describing a golfer who comes OTT. A traditional golfer should never come OTT if he learns how to execute the downswing correctly. I described the "correct" downswing action in great detail in my downswing chapter and in my Book Review: The Slot Swing - Jim McLean review paper. I used the following composite photo to show how the intact power package drops into the "space" below the right shoulder if the downswing is "correctly" sequenced.

Ben Hogan "slotting" his club in the early downswing - capture images from his swing video [9]

Although Ben Hogan is turning his pelvis and shoulders in a horizontal manner, he has no problem dropping his intact power package (consisting of the loaded left arm flying wedge [yellow], right forearm flying wedge [red] and right upper arm [green]) into the "space" below his right shoulder, and thereby "correctly" shallowing-out his clubshaft. Hogan's hands are not moving "outside the correct downswing path" - even though his "hips and shoulders are turning".

Clubhead lag

The right arm straightens too soon and releases the wrist hinge, so clubhead lag is lost. Then the arms start to roll over and move the club on an outside path. The club quickly gets heavy, dissipating any remaining wrist hinge.

My comment: It is astonishing to read a statement by Bennett/Plummer that claims that a traditional golfer would straighten his right arm during the early downswing. Traditional golf instructional teaching instructs a traditional/conventional golfer to keep the power package intact during the early downswing - note how Ben Hogan's right elbow is still bent at a right-angle in image 2/3 above (when his left arm is roughly parallel to the ground).

Here is another example.

Stuart Appleby downswing - capture images from his swing video [8]

Note that Stuart Appleby's right elbow is still bent at a right angle in image 2 (when his left arm is roughly parallel to the ground). In fact, a traditional golfer, like Stuart Appleby, should also keep the right elbow bent in the mid-downswing (images 3 and 4) and only straighten the right elbow in the late downswing (between image 4 and image 5).

Note that Stuart Appleby has not lost any clubhead lag at the end of his early downswing (image 2).

Impact

Lower body actionThe lower body provides little leverage or power at impact, because there is no spring in the knees or forward thrust from the hips.

My comment: Thank goodness! I think that it would be a major mistake for a traditional golfer to try to get additional swing power by a pelvic forward thrust action at (or near) impact. Most traditional golfers are swingers, and a swinger must power the swing through the sequential release of power accumulator #4, then PA#2 and then PA#3 - see my How to Power the Golf Swing review paper. PA#4 is released by the pivot-drive action in the early-mid downswing, and during this pivot-drive action the rotating pelvis helps to power the release of PA#4. The rotating pelvis only helps to power the release of PA#4 in the early downswing, and not the late downswing. PA#2 is released in the mid-late downswing through a passive centrifugal action, and PA#3 is passively released in the late downswing during the release swivel action (when the left forearm passively supinates into impact). The pelvis/legs/knees should not be involved in the release of PA#2 or PA#3.

Swing path

The club swings through impact on an out-to-in path, cutting across the ball and typically causing fades or slices.

My comment: This assertion is obviously incorrect. The clubhead path should never be out-to-in through impact in a traditional golf swing - that is a major mistake that is usually caused by an OTT move. The "correct" clubhead swing path should always be in-to-square-to-in in a traditional golfer, who swings his clubshaft on-plane throughout the downswing and followthrough.

Here is an example of a traditional golfer - Kevin Na - who has the "correct" clubhead swingpath through impact.

Kevin Na - clubhead swing path

Kevin Na, a traditional golfer, has the standard in-to-square-to-in clubhead path through the impact zone - because he is keeping his clubshaft on-plane throughout the downswing and followthrough.

Face angle

The clubface is open to the swing path because the club cut across the ball, so the face makes glancing contact, imparting slice spin and increasing loft at impact. The ball will curve to the right.

My comment: Bennett/Plummer are describing an unskilled golfer who comes OTT and generates an out-to-in clubhead path with an open clubface at impact. A skilled traditional golfer should have learnt how to control his clubhead path and clubface angle through the impact zone, so that he can avoid this major swing fault.

Low point

With the weight back, the swing reaches its low point behind the ball, causing either a fat shot or thin contact on the upswing.

My comment: Bennett/Plummer use the following photograph in their book [1] to depict a traditional/conventional golfer at impact.

Bennett/Plummer's depiction of a traditional golfer at impact - from reference number [1]

Note the i) square pelvis; ii) right heel still flat on the ground with significant body weight still on the right foot; iii) bent left arm; iv) bent left wrist; and v) straightened right wrist at impact.

Any website visitor, who has previously read my golf website's chapters and review papers, knows that a skilled traditional golfer would never look like that "golfer" at impact.

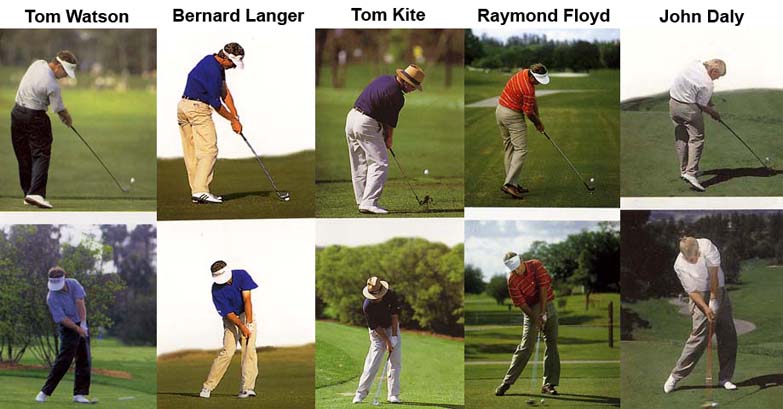

Here is composite image of five traditional golfers at impact - Tom Watson, Bernard Langer, Tom Kite, Raymond Floyd, John Daly.

Impact alignments in five traditional golfers - from reference number [10]

Note that all of these 5 traditional golfers have similar impact alignments - i) most of their weight is situated over a straightened/braced left leg; ii) their right leg is significantly unweighted iii) flat left wrist; iv) bent right wrist; v) straight left arm and and vi) open pelvis.

Followthrough (right arm parallel to the ground)

Wrist anglesThe wrists continue to break down and roll over until the right wrist is flat and the left wrist is bent back. This causes the clubhead to pass the handle, flipping the club upward.

My comment: If Bennett/Plummer believe that a traditional/conventional golfer is instructed to bend the left wrist through impact, then they manifest an astonishing lack of knowledge of the mechanics/biomechanics of the traditional golf swing. I have discussed this issue in many of my review papers, and the "correct" left wrist action in the followthrough in a swinger is a horizontal hinging action. During a horizontal hinging action, the left wrist remains flat and vertical to the ground as the left upper limb/clubshaft rotate at the same rpm around to the left.

Here is an example of the correct left wrist action during the followthrough.

Tiger Woods performing a horizontal hinging action during the followthrough - capture images from his swing video [11]

Note how Tiger Woods' left wrist remains flat and vertical to the ground during the followthrough - as the left arm and clubshaft rotate around to the left at the same rpm. Note that the clubhead end of the clubshaft is rotating at the same speed as the grip end of the club, and that there is no flipping of the clubhead passed the handle (and left hand).

A traditional golfer, who is a hitter, may employ angled hinging (rather than horizontal hinging) in the followthrough, but the left wrist should still remain flat during an angled hinging action.

Spine extensionWith the shoulders continuing to turn level, the spine tips back, but the absence of any springing action from the legs keeps the upper body short and compacted.

My comment: Bennett/Plummer's statement that the shoulders continue to turn level during the followthrough demonstrates that they simply do not understand the biomechanics of the traditional/conventional golf swing. Look at the shoulder turn angle in those 5 traditional golfers at impact , and look at Tiger Woods' shoulder turn angle in the above photo - note that they all have a steep shoulder turn at impact, and immediately beyond impact. None of those golfers has a short/compacted upper body in the followthrough - note how high their left shoulder is at impact (the left shoulder has moved up-and-away from the ball when the upper torso rotates along a steeper turn angle in the late downswing/followthrough).

In a traditional golf swing, the shoulders only turn level in the early-mid downswing. During the late downswing and followthrough, the shoulder turn angle becomes progressively steeper as the golfer acquires more secondary axis tilt. All good traditional golfers develop secondary axis tilt, which allows their right shoulder to more easily move downplane so that is moves steeply under the chin during the followthrough. A key biomechanical fact that allows the right shoulder to more easily move downplane under the chin through the early followthrough, is the presence of an open pelvis - because it reorients the lumbar vertebra, so that they face more rightwards (about 20-40 degrees to the right of the ball-target line). If a golfer has increased rightwards tilt in the late downswing/followthrough and the front of the vertberal bodies face more rightwards, then the upper body (shoulders) will rotate more steeply around the spine - and that will cause the left shoulder to move up-and-away, thus preventing the upper body from being "short and compacted".

Hip turn

The hips have not pushed forward, so they spin out weakly, the hip center staying between the feet.

My comment: Bennett/Plummer use the following photograph in their book to demonstrate their perception of a traditional golfer in the followthrough.

Bennett/Plummer's depiction of a traditional golfer in the followthrough - from reference number [1]

Note how they have depicted the pelvis as stalling through impact - the pelvis has remained relatively square to the ball-target line.

However, stalling of the pelvis should never happen in a skilled traditional golfer's swing. The pelvis should continue to rotate inside-left as part of a steady continuation of the "left hip clearing action" that started in the early downswing. Look at Tiger Woods' belt buckle in the above photo - note how his pelvis continues to actively rotate leftwards during the followthrough (in image 4 his pelvis is approximately 50-60 degrees open to the ball-target line).

Leg action

The right knee stays in place, and too much weight stays on the right foot.

My comment: This observation may apply to Bennett/Plummer's "conceptual idea" of a traditional golf swing - see the above photo.

However, in a "correctly executed" traditional golfer's swing, virtually all of a golfer's weight (>80%) should be over the straight left leg at impact, and even more so during the followthrough. Look again at these photographs of 5 traditional golfers at impact - they do not look like the Bennett/Plummer model of a traditional golfer, who has a stalled pivot action at impact.

Five traditional golfer at impact - from reference number [10]

Getting to this "impact alignment" condition is a key requirement of the traditional/conventional golf swing, and if a traditional golfer learns how to consistently achieve these impact alignments, then he should have no problem fulfilling Bennett/Plummer's first fundamental requirement - "hitting the ground at the same place every time".

Understanding how to control low point - a conceptual methodology for traditional/conventional golfers:

After reading their personal (biased) description of the traditional golf swing, I am not surprised that Bennett/Plummer felt the need to develop an alternative golf style, that would allow them to "hit the ground at the same place every time". Hitting the ground consistently at the same place means that a golfer has acquired a consistent golf swing that has a consistent low point location - always at the same place on the ground between his feet. To achieve that goal, Bennett/Plummer developed a "ferris-wheel" type of motion of the upper/lower torso for their S&T swing, so that type of torso motion would allow a golfer to keep the upper swing center (shoulder center) stationary throughout the swing. If a golfer is concerned about the long-term effects of a "ferris wheel" type of torso motion on the lumbar spine, then he may wonder if it is possible to consistently control low point using a rotary torso motion - as depicted in a previous section of this review paper.I believe that it is very easy for a traditional golfer to achieve a consistent low low point location when using a rotary torso motion, and I will describe the basic principles in this section of this review paper.

I define "low point" as the lowest point of the clubhead arc (nadir of the clubhead arc) in an optimally-executed swing - the point when the clubhead changes direction from moving down-and-out to up-and-in. Note that I have specified that the golf swing must be "optimally executed". I think that it is meaningless to use the term "low point" for a poorly executed golf swing, because I believe that the term is best used as a mental concept, rather than as a descriptive concept that applies to an unskilled golfer's particular swing. For example, if an unskilled golfer places the ball 2 inches inside his left heel, and then hits the ground a few inches behind the ball, then it doesn't mean that his low point is behind the ball. It simply means that he hit a "fat shot" and that he never generated an optimal clubhead arc that would situate the low point at its "correct" location.

What is the "correct" location for low point in a traditional swing?

I believe that the "correct" location for low point is an imaginary point on (or under) the ground that is situated just inside the left foot (that imaginary point will be in the air, above the ground, for a driver swing because the clubhead never impacts the ground). Low point is the point when the i) left arm and clubshaft are in a straight-line relationship, and ii) where the clubshaft is simultaneously vertical to the ground. Here is a photograph of John Daly and VJ Singh at low point.

John Daly and VJ Singh at low point