What is the twistaway maneuver and why should a golfer never deliberately use it in his full golf swing?

Click here to go back to the video project's index page.

The term "twistaway" was apparently coined by one of Brian Manzella's student golfers, and Brian Manzella recommends that a golfer should use the twistaway maneuver to close the clubface during the downswing, so that a golfer can acquire a square clubface by impact.

Brian Manzella discusses the twistaway maneuver between the 6:30 - 9:00 minute time point of his video called "The Science of Smash".

In his video, Brian Manzella claims that a golfer has to actively twist the golf club handle clockwise about its longitudinal axis at some time point during the downswing in order to close the clubface, and he refers to this active clubface-closing phenomenon (due to the twistaway maneuver) as equivalent to applying a positive gamma torque to the clubshaft.

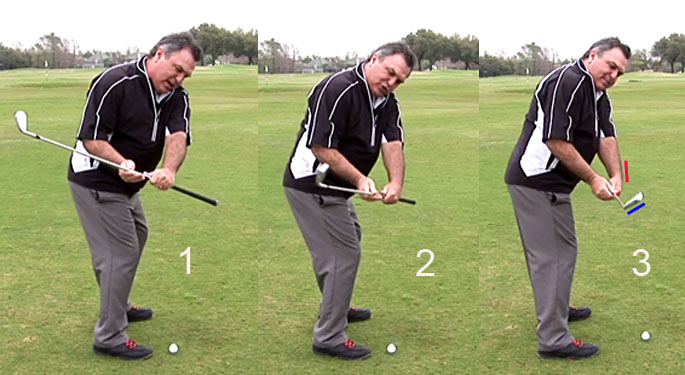

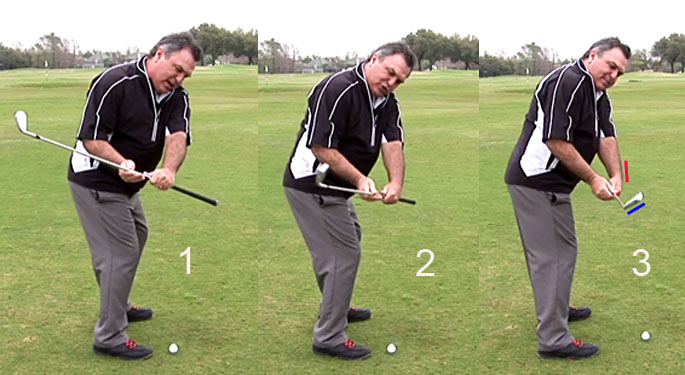

Here is a composite capture image of Brian Manzella demonstrating the twistaway maneuver.

Brian Manzella suggests that the twistaway manuever should be executed at roughly the P5 position (when the left arm becomes parallel to the ground at the end of the early downswing), although he recommends an earlier execution of the twistaway maneuver in golfers who have a strong tendency to slice the ball.

Image 1 shows Brian Manzella at the P5 position with an intact LAFW. Note that he has a slightly dorsiflexed (cupped) left wrist and note that the clubface is parallel to the watchface area of his left lower forearm (which is expected if a golfer adopts a neutral left hand grip).

Image 2 shows Brian Manzella at the ~P5.5 position. Note that his left wrist is now palmar flexed (bowed) and note that the clubface is becoming more closed (relative to the clubhead arc and also relative to watchface area of his left lower forearm).

Image 3 shows Brian Manzella at the P6 position. Note that his left wrist is still palmar flexed (bowed) and note that the clubface (represented by the short blue line) is closed relative to the clubhead arc and also closed relative to the watchface area of his left lower forearm (represented by the short red line).

What causes the clubface to become so closed at the P6 position? The correct answer is that Brian Manzella is performing a twistaway maneuver between P5 and P6 in order to twist the clubshaft clockwise about its longitudinal axis, so that the clubface becomes increasingly closed relative to the clubhead arc.

Brian Manzella claims in his video that if he can get the clubface closed relative to the clubhead arc by P6 (secondary to the biomechanical action of executing a twistaway manuever), that he can then simply turn his body towards impact and he will then automatically have a square clubface by impact - because he has already closed the clubface relative to the clubhead arc as a result of executing the twistaway maneuver during his mid-downswing. Brian Manzella's claim would be a reasonable claim if he could maintain the twistaway maneuver unchanged all the way from P6 to impact, but I believe that it is impossible - and I have never seen a professional golfer still maintaining a twistaway maneuver at impact (where the clubface is still markedly closed relative to the watchface area of the left lower forearm). To fully understand why I believe that it is biomechanically impossible, you first need to understand the "real life" biomechanics underlying the execution of a twistaway maneuver.

Brian Manzella may claim that the closed clubface that occurs during the execution of a twistaway maneuver is causally due to left wrist palmar flexion, but that claim would be incorrect because the true cause of the clubface-closing phenomenon is a finger-torquing action that twists the clubshaft about its longitudinal axis and the accompanying left wrist palmar flexion seen during the execution of a twistaway maneuver is only a secondary biomechanical "effect" of the twistaway maneuver.

If a golfer (who adopts a neural left hand grip) deliberately palmar flexes the left wrist when the left arm/clubshaft is held straight out in front of his body at the level of his left shoulder socket area, what affect will it have on the clubshaft and the clubface?

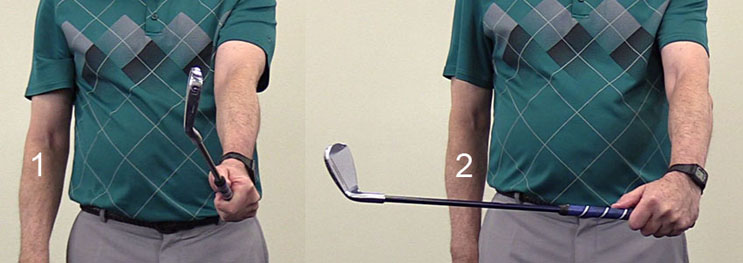

Here is the correct answer - using capture images from my part 6 video.

In image 1, I am holding the clubshaft straight-in-line with my left arm, which

is extended slightly away from my body. Note that I am adopting a neutral left

hand grip, and that the back of my left wrist is slightly dorsiflexed (cupped)

due to the fact that I am holding a rounded object in my left hand, which will then

naturally acquire a fist-like appearance. If the clubshaft is straight-in-line

with my left arm, then I have a GFLW and an intact LAFW. Note that the clubface

is parallel to the back of my GFLW and also parallel to the watchface area of my left lower arm.

Note that the toe of the clubhead is pointing straight upwards.

In image 2, I am deliberately palmar flexing (bowing) my left wrist using only my left wrist flexor muscles (flexor carpus radialis and flexor carpus ulnaris). Note that the "pure" left wrist palmar action causes the clubshaft to angulate backwards away from the target, but it doesn't close the clubface and the toe of the club is still pointing straight upwards.

Now, consider what would happen if I contracted my major finger flexor muscle (flexor digitorum profundus muscle) in my left forearm.

In image 1, I am holding the clubshaft straight-in-line with my left arm, which

is extended slightly away from my body. Note that I am adopting a neutral left

hand grip, and that the back of my left wrist is slightly dorsiflexed (cupped)

due to the fact that I am holding a rounded object in my left hand, which will then

naturally acquire a fist-like appearance. If the clubshaft is straight-in-line

with my left arm, then I have a GFLW and an intact LAFW. Note that the clubface

is parallel to the back of my GFLW and the watchface area of my left lower arm.

Note that the toe of the clubhead is pointing straight upwards.

In image 2, I am starting to actively contract my major finger flexor muscle (flexor digitorum profundus muscle) in my left forearm and that causes my fingers to clench tighter, and tighter, around the grip of the club. As I increase the finger-clenching power of my left hand, by increasingly contracting my flexor digitorum profundus in my left forearm, then my finger clenching action will torque the clubshaft about its longitudinal axis and cause the clubface to rotate counterclockwise (as viewed from above) so that the clubface becomes closed relative to the watchface area of my left lower forearm. Note that I have acquired an anatomically flat left wrist (very slightly palmar flexed left wrist) as a secondary result of the activation of the finger flexor digitorum profundus muscle and that causes my knuckles to move under my hand.

In image 3, I am activating my flexor digitorum profundus muscle in my left forearm with my maximal amount of muscular contractile force. Note that it causes my left hand's finger knuckles to curl under even more and it also causes my left wrist to become overtly palmar flexed (overtly bowed). Note that the clubface closes even more relative to the watchface area of the my left lower forearm.

This demonstration proves that the clubface-closing phenomenon seen in a twistaway maneuver is actually due to a finger-torquing action secondary to the activation of the flexor digitorum profundus muscle in the left forearm.

Now, why do I believe that it is biomechanically impossible to maintain a twistaway maneuver throughout the remainder of the downswing and all the way into impact (from P6 => P7)?

I believe that it is physically improbable (and maybe even physically impossible) that a professional golfer can maintain his maximum degree of contraction of his left forearm's flexor digitorum profundus muscle throughout his entire late downswing (between P6 and P7) when swinging a driver at a clubhead speed of >100mph. When the club releases in the late downswing, it increasingly creates a centrifugal (outward-directed) force that will stretch/extend the flexor profundus muscle in the left forearm and markedly decrease its finger-torquing power, so that very little finger-torquing action will still be present at impact.

In fact, I have never seen any professional golfer (who adopts a neutral left hand grip), and who seemingly executes a twistaway maneuver in his early-mid downswing, maintain a clubface that is closed relative to the watchface area of his left forearm throughout his entire P6 => P7 time period when swinging a driver at clubhead speeds of >100 mph. Have you? If you have, and if you can send me the appropriate documentary "evidence", then I will very happily send you $100 as a donation. I believe that there are two practical ways to correctly assess whether any significant "clubface-closing effect" is still present at impact if a golfer executes a twistaway manuever during his downswing action. First of all, there must be clear "evidence" at impact of a residual twistaway maneuver effect where the clubface is still significantly closed relative to the watchface area of the left lower forearm. Secondly, if a golfer (who uses a neutral left hand grip) is closing the clubface relative to the clubhead arc secondary to the execution of a twistaway maneuver, then he will obviously need less left forearm supination in his late downswing in order to acquire a square clubface at impact. Therefore, there must be definite visual "evidence" that the left forearm is less supinated at impact (compared to the situation when the same golfer doesn't use a twistaway maneuver). I have never seen a golf swing video where these two features, secondary to the use of a twistaway maneuver, are present - and that is why I retain the strong conviction that a twistaway maneuver has no "real life" (practical) clubface-closing utility in a full golf swing.

I think that the twistaway maneuver is an artificial biomechanical action that should never be used by a golfer who is using a standard TGM swinging technique, which involves the swinging motion of an intact LAFW/GFLW that is always "on-plane"; and where the clubface is naturally squared by impact due to the timely release of PA#3 (which is biomechanically due to a left forearm supinatory motion). During the left forearm supinatory motion, the club handle is naturally being twisted in a counterclockwise direction, and there is no rational reason why a golfer should think of increasing the degree of handle twisting torque via the biomechanical mechanism of a supplementary finger-torquing action.

Although I think that there is no rational reason to use a twistaway "finger-clenching" maneuver when using the intact LAFW/GFLW swing technique, that twistaway "finger-clenching" maneuver is very likely being used by golfers (like Gary Woodland) who use the alternative *"combined early left forearm supination and left wrist palmar flexion" technique.

(* I discussed the "combined early left forearm supination and left wrist palmar flexion" technique in part 7 of my video project, and I have discussed it in even greater detail in topic number 8 of this review paper)

Here are capture images of Gary Woodland performing his "combined early left forerarm supination and left wrist palmar flexion" technique.

During his early downswing, Gary Woodland uses the intact LAFW/GFLW technique.

However, when he gets his hands closer to the P5.5 position he converts to using

the "combined early left forearm supination and left wrist palmar flexion"

technique as he prepares to "turn his hands around the corner" towards the

target.

Image 1 shows him at the P6 position - note that the knuckles of his left hand appear to be "turned under" due to the finger-clenching effect of a twistaway maneuver and that causes the clubface to appear to be slightly closed relative to the watchface area of his left lower forearm. However, at impact (image 2), note that his knuckles are not "turned under" and his clubface is not closed relative to the watchface area of his left lower forearm - note that the back of his left lower forearm and clubface are both facing the target. Gary Woodland may still be using a finger-clenching action (by still contracting his flexor digitorum profundus muscle in his left forearm) in order to maintain a "stable" bowed left wrist through impact, and that finger-clenching action will give his bowed left wrist more mechanical stability through impact, but it didn't help him to close the clubface during his late downswing so that he didn't require as much left forearm supination during his late downswing's PA#3 release action. Note that his radial bone at the level of his left wrist is perpendicular to the ball-target line at impact, and that it is turned more counterclockwise than his left antecubital fossa, which means that he didn't use less left forearm supination during his PA#3 release action in order to square his clubface by impact.

Jeffrey Mann.

January 2017.