Head movements in the full golf swing

Click here to go back to the index page.

Introduction:

This review paper is on the topic of head movements in the full golf swing. Many beginner golfers are rigidly instructed to "keep the head still" during the golf swing without understanding the underlying biomechanical rationale for that frequently proferred piece of advice. In this paper, I will be discussing the reasons why so many golf instructors offer that advice, and I will discuss the advantages and disadvantages of unquestionably following that advice in an overly rigid manner. I personally believe that the head should move to a small degree during both the backswing and downswing, but that the movements of the head should be limited in both degree and direction - and the head movements should be biomechanically necessary movements, rather than unnecessary movements that disrupt the swing. I believe that if a golfer understands the fundamental biomechanics of a full golf swing, then he will better understand why the head moves in response to movements of the spine and torso.

Head movements during the golf swing:

I think that a good analogy for a golf swing is the pendular movement of a grandfather clock.

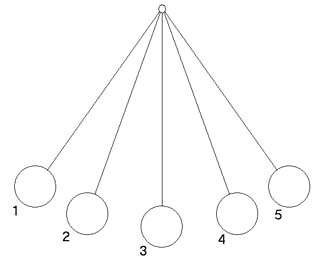

Pendular arc movement of a pendulum

The pendulum swings from a suspension point (fulcrum point) and the fulcrum point remains "fixed" in space during the entire arced movement of the pendulum. The "fixed" fulcrum point allows the pendulum to move along a perfectly symmetrical arc and the low point of the pendular swing arc is always at exactly the same spot (point 3 in the above image).The golf swing is similar to a grandfather clock, except that there are two arms, which are attached to the torso at the two shoulder socket joints. There are therefore two suspension points - one for each arm. The golf swing also consists of two pendulums arranged in a tandem arrangement via an interconnecting hinge joint - the arm and the clubshaft are hinged together at the wrists/hands.

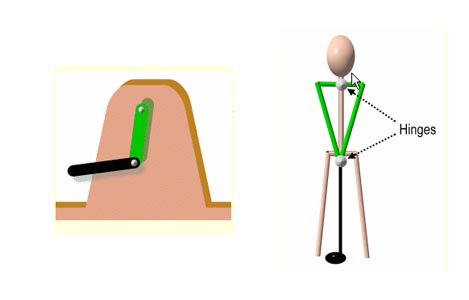

Double pendulum - from reference number [1]

The first image shows a double pendulum unit where the two pendular arms are hinged together, and the conjoined double-pendulum unit is centrally hinged at a "fixed" fulcrum point. The second image shows that in a golfer, the central pendular arm is represented by the golfer's two arms acting as a single central arm pendular unit, and the central arm pendular unit is hinged to the peripheral pendular unit (clubshaft) at the hands. Conceptually, the golfer would be mimicking the pendular action of a grandfather clock if the central hinge point (where the central pendular unit attaches to the torso) remains "fixed" in space during the entire swing - that arrangement would theoretically allow the golfer to produce a consistent clubhead swingarc and a consistent low point (point where the clubhead is closest to the ground). Note that David Tutelman has drawn the central hinge point in his model at a point where a line drawn between the two shoulder sockets intersects the spine, and that point is midway between the shoulder sockets. In a human golfer, a comparable central fulcrum point for the two-arm unit would be a point within the upper torso midway between the two shoulder sockets and just in front of the second thoracic vertebra - and that imaginary fulcrum point is labelled the upper swing center. Does the upper swing center remain in a relatively fixed position during the downswing and followthrough?Consider this image of Aaron Baddeley's swing.

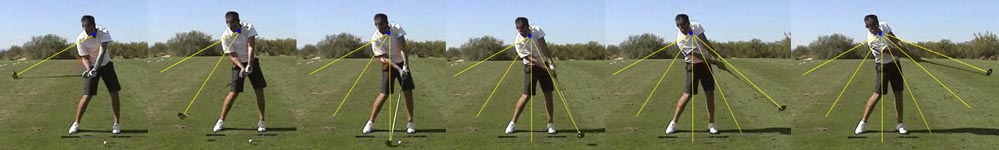

Capture images from a swing video of Aaron Baddeley's driver swing

I produced this series of images using the V1 Home Swing Analyser program. I placed a blue dot over Aaron Baddeley's upper swing center, and it can be seen that the upper swing center remains fixed in location during the mid-late downswing and early followthrough. Note that the yellow lines (drawn from the upper swing center to the clubhead) gets progressively longer as the club releases and the right elbow straightens. In that sense, a "real world" golfer is different to David Tutelman's simplistic golfer model - where the two arms are both fully extended and of fixed length at all time-points throughout the swing. I have studied the swings of many professional golfers and they all keep their upper swing center stationary during the downswing. They never let the upper swing center slide forward in the direction of the target. A beginner golfer needs to learn to keep his upper swing center stationary during the golf swing, but it is difficult for a beginner golfer to "feel" where his upper swing center is located in space, and that's why he needs to understand that there is a constant spatial relationship between the movement of the upper swing center and the movement of the head - because he can then monitor his head movements and know that it accurately reflects the movement of the upper swing center.Note the position of Aaron Baddeley's head as it relates to the location of the upper swing center in the above series of capture images. Note that the left side of his head/face never gets ahead/forward of the upper swing center (never gets closer to the target) at any time-point in the downswing and early followthrough. Although his head/face has a variable degree of rightwards tilt away from the target, note that his head remains stationary from a left-to-right perspective throughout the downswing and early followthrough. If one drops a vertical line down from the left side of the head/face down to the ground in image 1, it will hit the ground at a point that is behind the center of his stance, and the left side of his head/face never slides left-laterally beyond that point towards the target during the remainder of the downswing. In other words, a beginner golfer needs to learn to keep the head very still (stationary) from a left-to-right perspective. It is perfectly acceptable if the head swivels around in a horizontal manner or drops down slightly (right side of the head tilts towards the ground) during the downswing - as long as the left side of the head/face doesn't get closer to the target.

Consider the normal movements of the upper swing center and head during the backswing and downswing by studying Stuart Appleby's driver swing.

Stuart Appleby's driver swing - capture images from a swing video [1]

This composite image shows Stuart Appleby at address (image1), at the end-backswing postion (image 2), and at impact (image 3). I placed red lines alongside his head at adddress, a blue dot over the position of the upper swing center, and the yellow line demonstrates his degree of spinal tilt (which varies at different time-points in the swing). The white lines were drawn by the commentator who produced the swing video. He placed a white line alongside Stuart Appleby's outer right leg at address, and white lines alongside his outer left leg and outer left torso at impact - to demonstrate the amount of pelvic and upper torso shift that occurs during the swing.Note how much Stuart Appleby's pelvis and lower body moves left-laterally during the downswing, while his upper torso remains behind with virtually no movement of the upper swing center away from its "fixed" fulcrum-point position - which was established at address. Because the upper swing center remained near-stationary during the entire downswing while the pelvis shifted left-laterally, his spine acquired a greater degree of rightwards tilt away from the target (secondary axis tilt) during the downswing.

Note that there is virtually no movement of Stuart Appleby's head during the backswing, other than a slight horizontal swivelling movement of his head. Many golfer's have a natural tendency to swivel the head rightwards during the backswing as the left shoulder approximates the chin - and this head swivelling movement allows the shoulders to turn fully without any impedance from the chin. Note that his head doesn't lift up during the backswing, and the head only rotates horizontally around to the right to a small degree. This rotary movement of the head mainly occurs at the level of the joint between the first cervical vertebra (atlas) and second cervical vertebra (axis), and it doesn't necessarily indicate that there has been any rotation or tilting of the rest of the cervical spine (which consists of seven cervical vertebra). At address, Stuart Appleby has a small amount of rightwards spinal tilt, which doesn't increase in degree during the backswing. During the downswing, there is a significant left-lateral shift of the pelvis and that causes the lumbar spine to also move left-laterally to a significant degree. If the upper swing center, and therefore upper thoracic spine, is kept stationary while the lumbar spine (which is rigidly attached to the pelvis) moves left-laterally, the degree of rightwards spinal tilt must increase (image 3). Note that Stuart Appleby's head tilts/drops slightly to the right, and that is simply due to the fact that the cervical spine has a natural tendency to align itself with the rest of the spine (thoracic and lumbar spine) and the head also has a natural tendency to align itself in line with the cervical spine. Most importantly, note that left side of Stuart Appleby's head/face never moves left of the red line, which was placed alongside the left side of his head/face at address, at any time-point in the backswing or downswing - even though the lower body has shifted left-laterally towards the target to a significant degree during the downswing.

If one examines Aaron Baddeley's driver swing, one will note exactly the same phenomena.

Aaron Baddeley's driver swing - capture images from a swing video

This composite image shows Aaron Baddely at address (image1), at the end-backswing postion (image 2), and at impact (image 3). I placed red lines alongside his head at adddress, and a blue dot over the position of the upper swing center. Note that Aaron Baddely has a slight degree of rightwards spinal tilt at address, and that a vertical line drawn down from the center of his head hits the ground at a point that is behind the center of his stance. Note that Aaron Baddeley keeps his head near-stationary during the backswing, and that he doesn't have the need to swivel his head to the right in order to get an adequate shoulder turn. He also doesn't lift his head during the backswing. Note how his upper swing center doesn't move out-of-position during the downswing, and that the left side of his head doesn't move left of the left red line. Note that the right side of his head tilts down towards the ground in the late downswing (as if he wants to allow water to run out of his right earcanal) - secondary to the increased rightwards spinal tilt (secondary axis tilt).Finally, consider the movement of Tiger Woods' upper swing center and head during his driver swing.

Tiger Woods driver swing - capture images from a swing video

This composite image shows Tiger Woods at address (image1), at the end-backswing postion (image 2), and at impact (image 3). I placed red lines alongside his head at adddress, a blue dot over the position of the upper swing center, and the yellow line demonstrates his degree of spinal tilt (which varies at different time-points in the swing). Note that Tiger Woods has a slight degree of rightwards spinal tilt at address, and that causes his head to be vertically above a point on the ground that is behind the center of his stance. Note that Tiger Woods swivels his head to the right during the backswing, and that it allows him to get a full shoulder turn without the left shoulder hitting the chin. Note that his upper swing center doesn't move forward during the downswing, and that it is at the same location-point where it was located at address - despite a significant shift of the pelvis left-laterally. Note that his head drops down a lot during the downswing. However, note that the left side of his head never gets ahead of the left red line. Tiger Woods is not really disadvantaged by his excessive head dropping, which causes the cervical spine not to be aligned straight-in-line with the thoracic/lumbar spine, because it doesn't affect the position of the upper swing center. The cervical spine is very flexible in most young golfers and it can move about independently of the rest of the spine. Many professional golfers drop their head downwards like Tiger Woods when hitting a driver, and it doesn't affect their ability to hit the ball well because it doesn't cause the upper swing center to move out-of-position.A beginner golfer can learn a great deal about "correct" head movements from these capture images of these three professional golfers. He should understand that his key goal is keeping the upper swing center stationary near its address-position location throughout the backswing and downswing, and and that he should specifically avoid allowing the upper swing center to move ahead/forward in the direction of the target in the downswing. He can achieve that goal by ensuring that the left side of his head/face never moves ahead/forward in the direction of the target during the downswing. He should also realise that it is perfectly acceptable to allow the head to swivel horizontally away from the target during the backswing if it allows him to avoid having the left shoulder bump forcefully against the chin. He should also realise that the right side of the head will have a natural tendency to tilt in the direction of the ground during a full driver downswing, and that his head may even drop down slightly.

I have discussed the "correct" movements of the head as seen from a face-on view perspective. Now consider "correct" head movements from a down-the-line perspective.

Aaron Baddeley driver swing - capture images from a swing video

Note that I have drawn a red line on the top of Aaron Baddeley's head at address (image 1). Note that Arron Baddeley maintains a constant spine angle during the backswing and that the top of his head doesn't lift above that red line (image 2). Note that his head drops down slightly in the early downswing - during the hip squaring action when the knees become slightly more flexed (image 3). Note that the top of his head is still below the red line at impact (image 4) - the head is slightly lower than the red line because he has developed a significant degree of secondary axis tilt by impact. Most importantly from a beginner golfer's perspective, is the fact that the top of the head never lifts above the red line during either the backswing or downswing. Many beginner golfers have a tendency to lift their heads, and lose their spine angle, in the late backswing and/or at impact. That's a major fault that must be avoided. A beginner golfer golfer must learn to maintain a constant spine angle during both the backswing and downswing.Finally, consider the "correct" head movements when viewing a golfer from above - here is a birds-eye view of a professional quality swing.

Birds-eye view of an iron swing - capture images from a swing video [3]

At address (image 1), the head and neck is roughly held square to the ball-target line (see white marks on the back of the golfer's hat) and the eye line (straight line between the eyeballs) is therefore parallel to the ball-target line. Note that the pelvis, and therefore face-orientation of the lumbar spine, is parallel to the ball-target line, and that there is minimal rightwards spinal tilt.

At the end-backswing position (image 2), the pelvis has rotated about 50 degrees while the shoulders have rotated about 90 degrees. The fact that the shoulders have rotated 40 degrees more than the pelvis means that the thoracic spine is torqued so that it faces more rightwards than the lumbar spine (which faces about 50 degrees rightwards). The torquing of the thoracic spine to the right causes the cervical spine to also have a tendency to rotate slightly rightwards and that induces the head to rotate slightly rightwards in sympathetic alignment with the cervical spine. Note how the front bill of the golfer's hat has rotated a few inches to the right. The golfer may also be turning his head deliberately to the right at the atlanto-axial joint (joint between the first and second cervical vertebra) to prevent his left shoulder hitting his chin.

During the early downswing, the pelvis becomes square to the ball-target line and that causes the lumbar vertebra to face the ball-target line. At the same time, the thoracic spine is starting to also rotate towards the target and that causes the cervical spine and head to move likewise (see image 3).

By impact (image 4), the pelvis is about 40 degrees open, and that means that the lumbar spine is facing right of the target. The shoulders are about 20 degrees open, which means that the thoracic spine is facing slightly to the right of the ball-target line. It is perfectly natural, and virtually automatic, for the cervical spine and head to also become oriented in that same general direction - note the position of the white spots on the back of the golfer's hat, which indicates that the golfer has swivelled his head leftwards.

During the late followthrough, when the clubshaft is parallel to the ball-target line and along the toe line (image 5), the front of the thoracic spine is facing the target. If the golfer let's his cervical spine and head swivel naturally/automatically, the head will have a natural tendency to also swivel in the direction of the target.

All these rotary/swivelling movements of the head are natural/automatic biomechanical phenomena that will happen naturally (unconsciously) in response to the swivelling/spiralling motions of the thoracic and cervical spine. A beginner golfer should not resist these natural head swivelling movements, because any resistance will impede the natural flowing motion of the spine/torso as it rotates during the swing. A golfer should think of his head swivelling in a horizontal arc that is sympathetically coordinated with the overall movements of the torso. Part of this horizontal swivelling movement of the head occurs due to movement of the entire cervical spine and part of it occurs due to independent head movements at the atlanto-axial joint. It is very important that the head swivelling arc (which is along an axis that is roughly perpendicular to the bent-over spine) be roughly parallel to the ball-target line. If one draws an imaginary straight line between the pupils of both eyes, then that imaginary straight line (eye line) should be moving along an arc that is roughly parallel to the ball-target line during the downswing.

See this swing video lesson by Mike Malaska on the eye line.

When you get to this linked page, click on the link to the "Stop Coming Over The Top" video lesson. In that video lesson Mike Malska demonstrates how one can avoid an OTT move by keeping the eyeline parallel to the ball-target line, or oriented slightly to the right of the ball-target line, throughout the downswing. A beginner golfer should practice this move when swivelling his head to the left during the downswing.

Jeff Mann.

March 2008.

Commentary, criticism and controversy:

Insightful comments from readers will be posted in this section.

References:

1. The Tutelman Site. Golf Physics.

http://www.tutelman.com/golf/design/swing1.php?ref=

2. Stuart Appleby swing video.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_jqJ9R2LypY&NR=1

3. Swing video of one of Slicefixer's students.

Available online at http://youtube.com/watch?v=iAkFST89yr8