Critical Update: How to Optimally Rotate the Pelvis during the Downswing

Click here to go back to the homepage.

Introduction:

In this review paper I will be detailing in considerable depth my updated

opinions regarding the optimal method of performing a rotary pelvic motion

during the downswing. I will specifically describe in great detail the anatomy

of the pelvis and pelvic girdle muscles, and the likely biomechanical actions

used by many professional golfers when they rotate their pelvis during their

downswing action. I will not be originating any "new" methods on how best to

perform the rotary motion of the pelvis during the downswing action, because the

world's greatest professional golfers already know how to optimally perform a

rotary pelvic motion during their downswing action, and I am merely presenting

my "beliefs/opinions" regarding the fundamental biomechanics that I believe they use when

they perform their rotary pelvic motion. I suspect that many modern-day golf instructors are

teaching a suboptimal pelvic motion technique and I also believe that many

amateur golfers are using the wrong muscles to perform a rotary pelvic motion

during their early-mid downswing. I think that those amateur golfers could

significantly improve their rotary pelvic motion during the downswing if they

would use the same pelvic motion biomechanics that are used by many professional

golfers (like Sam Snead, Ben Hogan, Jack Nicklaus, Arnold Palmer, Lew Worsham,

Jordan Spieth and Jason Day) and I hope that this review paper will provide

those amateur golfers with a much greater insight into the optimum way of

performing a rotary pelvic motion during the downswing.

I have produced a 1 hour 48 minute video to supplement this review paper, and I have posted that video on you-tube.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bByKt7LRP2g

In that *video I demonstrate many of the same fundamental principles that I discuss in this review paper, and I hope that the supplementary video will help interested readers better understand my opinions regarding the biomechanics of the "rotary pelvic motion during the backswing and downswing".

(* Note that I frequently/mistakenly referred to the greater trochanter as the greater tuberosity, and the lesser trochanter as the lesser tuberosity during my unedited/extemporaneous video presentation, and I occasionally mixed up words eg. using the word "left" when I obviously meant "right". Also, note that I am an inflexible 67 year old senior golfer who lacks the ability to demonstrate the rotary pelvic motions efficiently, so always remember to listen to what I am saying if my body motions are not condordant with I am saying at any time point during the video presentation)

Finally, note that I previously wrote a review paper regarding the topic of pelvic motion during the downswing - The Backswing and Downswing Hip Pivot Movements: Their Critical Role in the Golf Swing - but I now regard my personal opinions expressed in that review paper as being oversimplistic and outdated, and they no longer represent my personal point of view. My personal opinions expressed in this review paper more accurately represent my present-day's (much more refined) thinking regarding the rotary pelvic motion that happens during a professional golfer's downswing.

Explaining the anatomy and biomechanics of an optimal rotary pelvic motion during the backswing and downswing

To perform a high quality golf swing at a professional level, I believe that a golfer should use an active pivot action type of golf swing where the active pivot action essentially powers the golf swing (via the pivot-induced release of PA#4). The pivot action can be thought of as a sequential kinematic phenomenon where the lower body (pelvis) rotates first, and the upper torso rotates secondarily after a variable degree of time delay. Any degree of time delay may produce a finite degree of dynamic X factor stretching of the upper torso's musculature (which some golfers believe is biomechanically advantageous) and it obviously creates a greater amount of torso-pelvic separation during the transition to the downswing. The start of the counterclockwise pelvic rotation may begin in the late backswing (eg. between P3.75 and P4) or it may only start at the P4 position (defined as the moment that the club suddenly changes direction). I believe that a characteristic biomechanical feature of a good quality pivot action is that it is fundamentally a rotary motion of the torso that happens between the feet, and there should be no side-to-side swaying motion of the torso that moves the body beyond the lateral boundaries of the feet. A *small degree of left-lateral pelvic shift is acceptable during the early downswing, but the downswing motion of the pelvis should primarily be thought of as being rotary in nature.

(* I will describe a number of factors that determine the amount of left-lateral pelvic shift that can occur during the early downswing later in this review paper).

Consider an example of a golfer who perfectly exemplifies the rotary motion of the torso that should happen in a good quality, professional golf swing.

Back view video of Jamie Sadlowski's golf swing - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5gekd_JMFT4

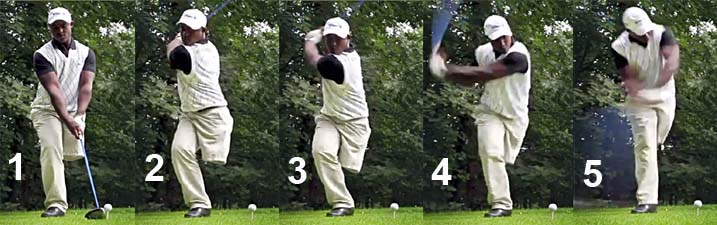

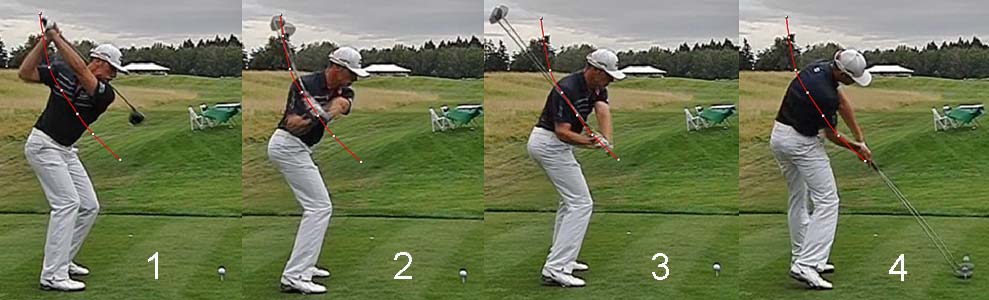

Here are capture images of Jamie Sadlowski's downswing action.

Image 1 shows Jamie Sadlowski at his end-backswing position (P4 position). Note that he rotated his pelvis about 50-60 degrees clockwise during his backswing, but he rotated his upper torso (shoulders) much more than he rotated his pelvis thereby generating a finite amount of static X factor (torso-pelvic separation). Note that his pelvis and upper torso are centralised between his feet, and there is no evidence of any side-to-side swaying motion of his torso.

Image 2 shows his early downswing action which starts off with a counterclockwise rotation of his pelvis that automatically/naturally causes the lumbar spine to rotate counterclockwise to roughly the same degree. His upper torso starts to rotate momentarily later and it involves a counterclockwise rotation of the thoracic spine. Note how his pelvis and upper torso remain centralised between his feet and there is no evidence of any deliberate weight-shift during his early downswing action.

Image 3 is at the P5.5 mid-downswing position. Note that his pelvis still leads the upper torso from a rotary perspective and that his pelvis is more open than his upper torso (thorax) - and that allows him to more easily acquire secondary axis tilt and right lateral bend, that in turn makes it easier for him to slot his power package in an "in-to-out" manner and thereby avoid any roundhousing motion of his upper torso and arms.

Image 4 is at impact. Note that his pelvis is more open than his upper torso. Note that both his pelvis and upper torso are still roughly centralised between his feet and there is no evidence of any overt swaying motion of his torso in a targetwards direction during his entire downswing action.

Before I continue to discuss the biomechanics underlying the rotary motion of the pelvis during the downswing, I will first point out certain anatomical features of the pelvis.

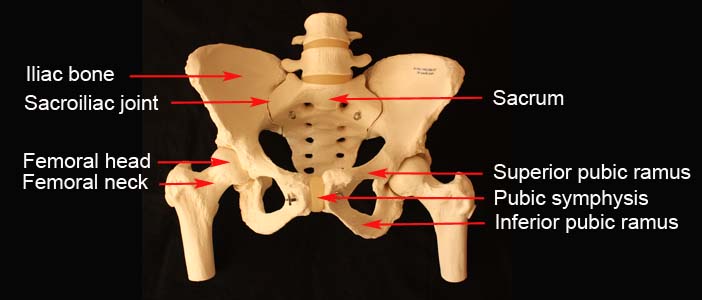

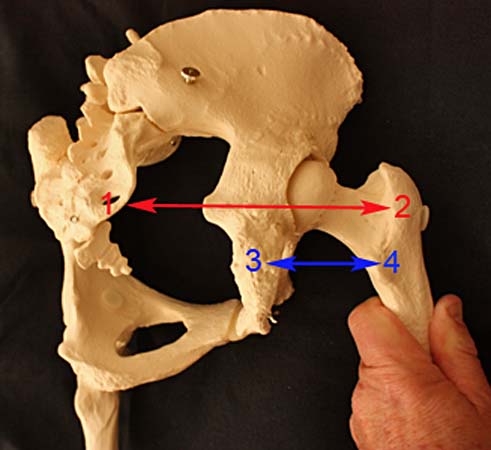

Consider two photographic images that I took of a plastic cast-model of the human pelvis.

The pelvis can be thought of as basically consisting of two skeletal

half-structures (with each half consisting of iliac, pubic and ischial bony

subsections) that are conjoined together at the back by the sacrum (at the left

and right sacroiliac joints) and at the front by the ligamentous pubic symphysis (which can

be thought of as being equivalent to a joint). Because the sacro-iliac joints

and pubic symphysis are only lax during late pregnancy, it is useful to think of

the entire pelvis and sacrum as being an unitary bony (skeletal) structure that

can only rotate as a single rotating skeletal entity, which means that the left

side of the bony pelvis cannot rotate more (or less) than the right side of the

bony pelvis. Now, although the left half of the bony pelvis cannot rotate more

(or less) than the right half of the bony pelvis from an intrinsic skeletal

perspective, it is possible for the right half of the lower body (pelvis) to

rotate more (or less) than the left half of the lower body (pelvis) if one views

the rotational motion of the lower body (pelvis) from an extrinsic perspective - and what

makes this phenomenon biomechanically possible is that the pelvis has no single

axis of rotation that is centrally located. Any rotary motion of the pelvis

during the golf swing action occurs due

to joint motion happening at the level of the two hip joints, and it is

biomechanically possible for there to be more translational and rotational

motion happening at one of the hip joints (relative to the opposite hip joint)

because of the presence of biomechanical factors that affect each hip joint's resistance/impedance to

any translational (or rotational) motion happening at the level of each

hip joint.

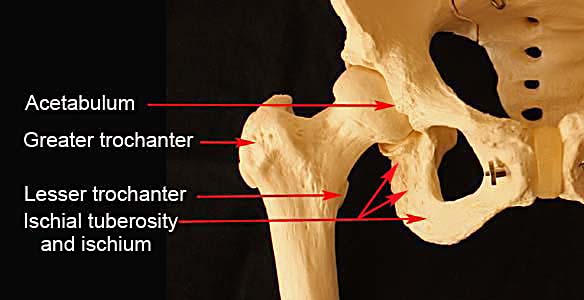

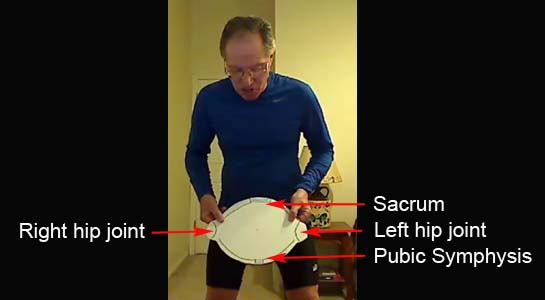

Consider this cardboard cut-out that is shaped to resemble the oval shape of a human pelvis.

Capture image from my video presentation.

Note that I am holding a piece of cardboard that has been shaped to resemble the oval-shaped human pelvis with two hip joints at opposite ends.

Now imagine what would happen if it were possible to create a humanoid robot that only had a single supporting leg that articulated with the pelvis centrally, so that the pelvis could rotate around the single/central vertical axis of that centralised leg.

In this demonstration (from my video), I have placed a bicycle spoke through a hole in the center of the cardboard pelvis, and that bicycle spoke represents a single/central pelvic axis around which the pelvis can rotate. Note that the bicycle spoke is being held perpendicular to the inclined plane (swingplane).

Image 1 shows the orientation of the pelvis at address, where the pelvis is square to the target, and where an imaginary horizontal line drawn between the two hip joints is parallel to the ball-target line (which is the base of the inclined plane). R1 represents the position of the right hip joint at address, and L1 represents the position of the left hip joint at address.

Image 2 shows what would happen if I rotate the pelvis clockwise by ~50 degrees in the direction of the curved red arrow (mimicing the pelvic rotation in the backswing). The right hip joint will move to position R2. While that is happening, the left hip joint will move in the direction of the curved blue arrow to position L2. The amount of movement of the left hip joint will be identical to the amount of movement of the right hip joint because the rotation of the pelvis is happening symmetrically around a single/centralised axis through the middle of the pelvis.

Image 3 shows what would happen if I rotate the pelvis counterclockwise so that the right hip joint moves from the R2 position to the R3 position (mimicing the pelvic rotation during the early downswing) - the left hip joint will move symmetrically by exactly the same amount from position L2 to position L3.

In other words, the two hip joints always move symmetrically by exactly the same amount during any clockwise (or counterclockwise) rotation of the pelvis.

As I previously stated, this phenomenon of a symmetrical rotational motion of the two hip joints doesn't necessarily happen in a "real life" golfer's golf swing action because there is no single/central axis of rotation. In a "real life" professional golfer who performs a rotary pelvic motion during the backswing/downswing, the pelvis rotates because of 3-D translational/rotational movements of the two femoral heads in 3-D space.

Consider the average amount of pelvic rotation that may occur in a skilled golfer's full golf swing action.

Image 1 represents the address position where the pelvis is square to the target, and where the horizontal pelvic axis between the two hip joints is parallel to the ball-target line (base of the inclined plane).

Image 2 shows the end-backswing position of the pelvis if it rotates clockwise by ~50 degrees during the backswing action.

Image 3 shows the pelvis at the end of the "hip-squaring phase" (which usually happens by P5) and note that the pelvis is again square having rotated counterclockwise by ~50 degrees during the early downswing.

Image 4 shows an open pelvis at impact with the pelvis open by ~40 degrees.

The total amount of counterclockwise rotation of the pelvis happening in the downswing is ~90 degrees. Note that the left hip joint has rotated counterclockwise by ~90 degrees during the downswing and this represents the "left hip clearing" action where the left hip joint rotates counterclockwise away from the ball-target line in the direction of the tush line (which is an imaginary line drawn against the back of the right buttocks at the P4 position) during the downswing action. Note that according to my arbitrary definition of the *"left hip clearing" action, it starts at P4 and ends at impact, and it consists of two rotational phases - i) phase 1 is the "hip-squaring phase" that happens between P4 and P5 and ii) phase 2 happens between P5 and impact. I have arbitrarily divided the "left hip clearing" action (which is really a continuous/non-interrupted rotary motion) into those two phases because I believe that different pelvic girdle muscles and different biomechanical actions are used to rotate the pelvis in phase 1 (compared to phase 2).

(* Many golf instructors talk of the "left hip clearing action" in a very different manner, and they refer to the "left hip clearing action" as happening in the later downswing and they believe that the pelvis must first shift left-laterally towards the target in the early downswing before one can perform the counterclockwise rotational pelvic motion [that represents a "left hip-clearing action" where the left hip joint area of the left pelvis rotates back towards the tush line]. I believe that it is fundamentally incorrect to believe that it is mandatory to shift the pelvis left-laterally [in order to first get the left leg weight-pressure loaded] before one initiates the counterclockwise rotation of the pelvis and I will provide many pro golfer-examples of how the pelvis starts to rotate counterclockwise from the very start of the downswing without any need for a mandatory/preliminary weight-shift of the pelvis in a targetwards direction.)

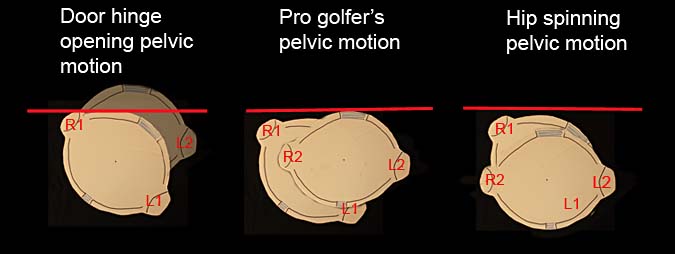

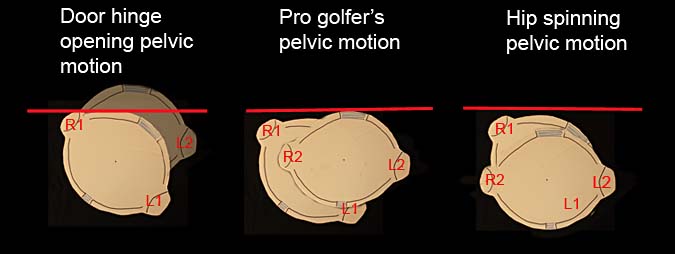

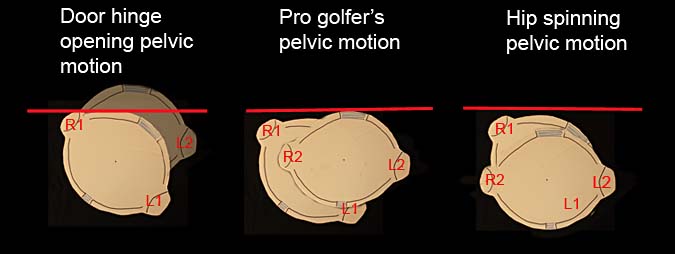

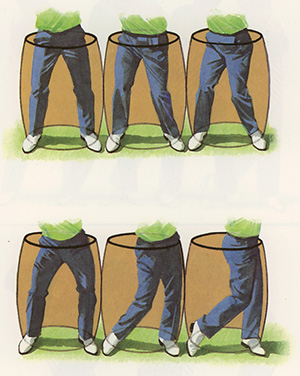

Now, consider three different rotary-translational pelvic motion patterns that can happen in the early downswing (during the hip-squaring phase of the "left hip clearing" action).

I have used Photoshop to produce two images of the cardboard pelvis in each of the three pelvic motional patterns - the one image shows the pelvis at the P4 position (R1 being the position of the right hip joint and L1 being the position of the left hip joint) and the second image shows the pelvis at the end of the hip-squaring phase, which usually happens at/near the P5 position (R2 being the position of the right hip joint and L2 being the position of the left hip joint). The red line represents the tush line (imaginary line drawn against the back of the right buttocks at the P4 position).

Now, consider the first pelvic motional pattern - the door hinge opening type of pelvic motional pattern. In this type of pelvic motional pattern, note that the right hip joint remains in roughly the same location during the early downswing between P4 and P5, while the left hip joint gets pulled back towards the tush line to such a large degree that the back of the left buttock gets pulled back beyond the tush line by the end of the hip-squaring phase. In this particular type of "left hip clearing action" pattern, there is no lateral shift of the pelvis towards the target and the left hip joint simply gets pulled back towards the tush line during the "left hip clearing action" (like a door opening). The right hip joint can be considered to be equivalent to a "fixed" door hinge, which doesn't move its position while the door is opening. That's why I have arbitrarily labelled this type of pelvic motional pattern a "door hinge opening" type of pelvic motion.

Consider a golfer who manifests this "door hinge opening" type of pelvic motion pattern.

Manuel De Los Santos swing video - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aw-nt0eTb2w

Here are capture images from the swing video showing his downswing action

Note that Manuel De Los Santos has his left thigh amputated at the level of his

mid-thigh and he pivots over only one leg (right leg) during his downswing.

Image 1 shows Manuel De Los Santos at the address position with his pelvis square to the ball-target line.

Image 2 shows Manuel De Los Santos at his end-backswing position. Note that he has "turned into" his right hip joint during his backswing so that his right hip joint is in a state of internal rotation at the P4 position (due to the fact that he has rotated his pelvis more clockwise than he has rotated his right thigh). Note that his upper left thigh is hanging limply in a state of external rotation at the level of the left hip joint.

Image 3 shows how he starts to rotate his pelvis counterclockwise at the very start of his downswing and he is pulling his left buttocks (and left hip joint) back towards the tush line in an overt "left hip clearing action" manner.

Image 4 shows him at the end of the hip squaring phase, which happens slightly before he even reaches the P5 position. Note how far he has pulled his left buttocks (left hip joint) away from the ball-target line in the direction of the tush line and note that the back of his left buttock has even got further back than the tush line. Note that his right hip joint has not moved left-laterally towards the target, and it has only moved vertically upwards to a small degree as he slightly straightens his right thigh between P4.5 and P5.

Note that Manuel De Los Santos can perform a perfectly executed "left hip clearing action" without first shifting his weight left-laterally onto his left foot (which is non-existent). His downswing's pelvic motional pattern demonstrates that it is a fallacy to believe that a golfer must first shift the pelvis left-laterally in a weight-shifting manner before he performs a "left hip clearing action". In fact, it is biomechanically much easier for a two-legged golfer to externally rotate the left femur and withdraw the left hip joint in a "left hip clearing action" manner when the left leg is not significantly weight-pressure loaded than when it is more weight-pressure loaded. In a two-legged golfer, the average "COP-measurement under the left foot at P4 is 20-30% of the overall COP-measurement, while it is 50% of the overall COP-measurement at P5.

(*COP = center of pressure, and its measurement, using force plate technology, is a quantitative method of measuring the weight-pressure loading of the two feet at all times during the golf swing action, and the COP-measurement under each foot is usually expressed as a percentage of the overall COP-measurement)

Now, consider the second pelvic motional pattern - which I have arbitrarily labelled a "pro golfer's pelvic motion" pattern.

The pro golfer's pelvic motion pattern is used by the majority of professional golfers and it has the following characteristics. During the hip-squaring phase, the right hip joint remains nearly in the same location and it only moves a few inches in a targetwards and outwards direction, while the left hip joint moves much more in space and it mainly moves backwards in a direction that is away from the ball-target line and towards the tush line. There is very little (only 1-3") of left-lateral pelvic shift happening during this first phase of the "left hip clearing action" and there should be no deliberate attempt to shift one's body weight targetwards. Note that the back of the right buttock (or sacrum) remains at, or very near, the tush line during the entire duration of the early downswing between P4 and P5.

Consider a few golfer-examples who manifest this pattern.

Jamie Sadlowski

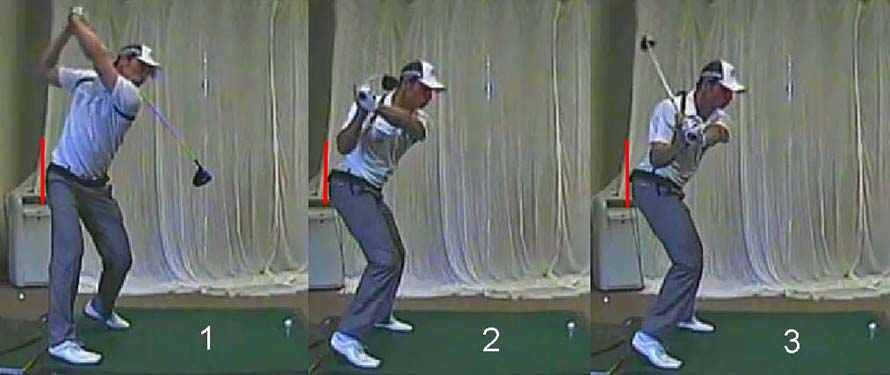

Here are capture images from a DTL video of Jamie Sadlowski's swing.

Image 1 shows Jamie Sadlowski at his P4 position. I have drawn a red line against the back of his right buttock at his end-backswing position and that red line represents the tush line.

Image 2 shows Jamie Sadlowski at the P4.5 postion and image 3 shows him at the P5 position (end of the hip squaring phase). Note how much Jamie Sadlowski has pulled his left hip joint (left buttock) back toward the tush line while still keeping his right buttock close to the tush line, thereby avoiding any premature outward motion of his right hip joint in the direction of the ball-target line.

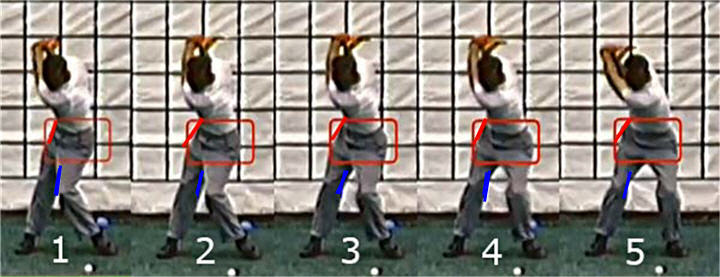

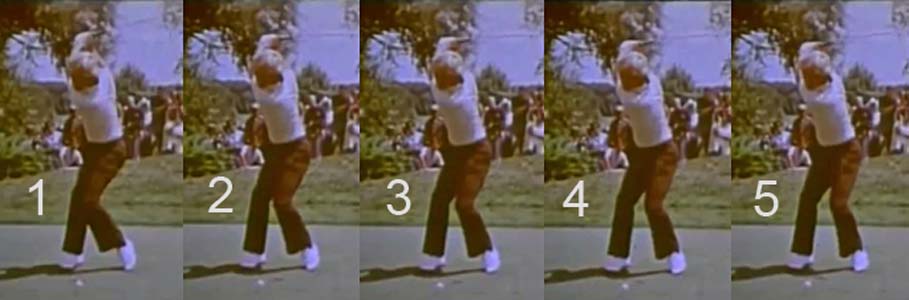

Consider face-on capture images of Jamie Sadlowski's early downswing action.

Image 1 is at P4 and image 5 is at P5. Note that he has a square pelvis at the

P5 position and both femurs are in a state of symmetrical external rotation at the

level of their respective hip joints, and he is therefore prototypically

manifesting the Sam Snead "sit-down" look. Note that his pelvis remains

centralised during his early downswing and there is minimal left-lateral pelvic

shift happening during the first phase of his "left hip clearing action". Note

that Jamie Sadlowksi does not "appear" to be shifting his body weight

left-laterally in a targetwards direction while he performs his rotary type of

pivot action (where he first rotates his pelvis counterclockwise, followed

shortly thereafter by a counterclockwise rotation of his upper torso around his

rightwards-tilted thoracic spine).

Jack Nicklaus

Birds-eye swing video of Jack Nicklaus and other professional golfers - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=StKkT9sTTtQ

Here are capture images of Jack Nicklaus' early downswing.

Image 1 shows Jack Nicklaus at his end-backswing position. I have drawn a red

line against the back of his right buttocks, and that red line represents the

tush line.

Image 2 shows Jack Nicklaus at P4.5 and image 3 shows Jack Nicklaus at the end of his hip-squaring phase (P5 position). Note how much he has pulled his left buttock back towards the tush line, while still keeping his right buttock against the tush line, during his early downswing's P4 => P5 time period.

Note that there is minimal left-lateral pelvic shift happening during his hip-squaring phase.

Birds-eye view swing videos are particularly useful in studying the movement of the right buttock away from the tush line in the early downswing, and here are capture images from another good quality birds-eye view swing video - featuring a student-golfer of Geoff Jones (aka Slicefixer).

Image 1 shows the student-golfer at his end-backswing position. I have drawn a

red line against the back of the right buttock, and that red line represents the

tush line.

Image 2 shows the student-golfer at the P5 position - at the end of his hip-squaring phase. Note how much he has pulled his left buttock (and therefore his left hip joint) back towards the tush line, while still keeping the back of his right buttock against the tush line.

Note that his pelvis has moved a few inches left-laterally during his hip-squaring action, which means that the right hip joint has moved targetwards to a small degree. However, note that his right hip joint is not prematurely moving outwards (towards the ball-target line) in a hip-spinning manner between P4 and P5.

I will shortly describe the biomechanics that underlie a pro golfer's pelvic motion pattern in great detail, but first consider the third pelvic motion pattern - the hip spinning pelvic motion pattern.

In the hip spinning pelvic motion pattern, the right hip joint

immediately moves outwards in the direction of the ball-target line, and the

right buttock therefore immediately leaves the tush line, at the very start of

the downswing. By contrast, the left hip joint doesn't move very much backwards

away from the ball-target line (towards the tush line) during that same time

period. At the end of the hip

squaring phase, both the left and right buttocks are many inches away from the

tush line. I regard the hip spinning pelvic motion pattern as being a suboptimal method

of rotating the pelvis during the downswing and I will describe the underlying causal biomechanics later in this review

paper.

Biomechanics underlying the performance of a pro golfer's pelvic motion pattern

I believe that this type of pelvic motion pattern is the

optimal method of rotating the pelvis in the early downswing between P4 and P5,

and I will describe the underlying biomechanics in great detail.

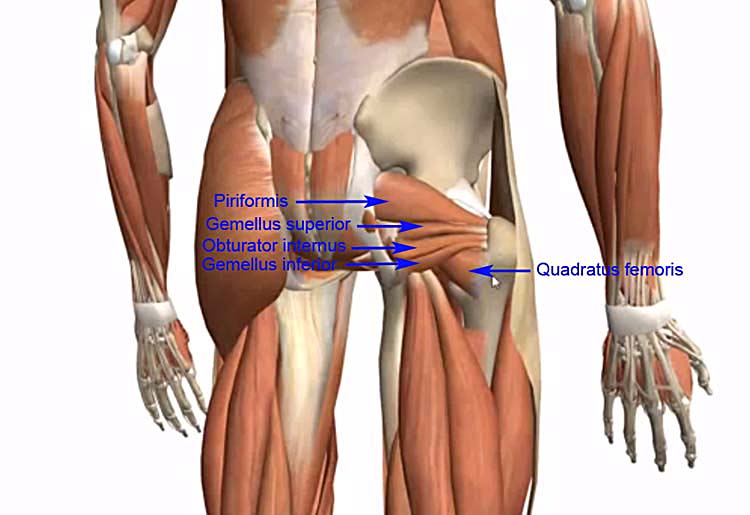

I believe that the key muscles used to perform this type of rotary pelvic motion are the right-sided and left-sided lateral pelvic rotator muscles, and it is important to understand how contraction of those muscles cause a counterclockwise rotation of the pelvis at the start of the downswing.

Here is a capture image (from that video) showing the 6 lateral pelvic rotator muscles.

I have pointed out the i) piriformis muscle, the

ii) gemellus superior

muscle, the iii) gemellus inferior muscle, the iv) obturator internus muscle, and

the v) quadratus femoris muscle. The vi) obturator externus muscle cannot be

seen from this viewing perspective because it is hidden beneath the

overlying lateral pelvic rotator muscles.

Note that I rotated the pelvis about 50 degrees clockwise before I took

this photograph of my plaster-cast pelvic model. Note that I have

prevented the right femur from rotating clockwise by the same amount, so

that the right femur becomes internally rotated in the

right hip joint. When the right femur is internally rotated in the right

hip joint, that means

that the points of insertion of the lateral pelvic

rotator muscles (points 2 and 4) are further away from their

points of origin (points 1 and 3). The points 1 - 2

represent the points of origin and insertion of the piriformis muscle and the points 3 - 4 represent the

points of origin and insertion of the quadratus femoris muscle. I have only referred to those two lateral

pelvic rotator muscles as representative examples, but all the 6 lateral

pelvic rotator muscles on the right side are similarly stretched at the

end-backswing position when the right femur is internally rotated in the

right hip joint.

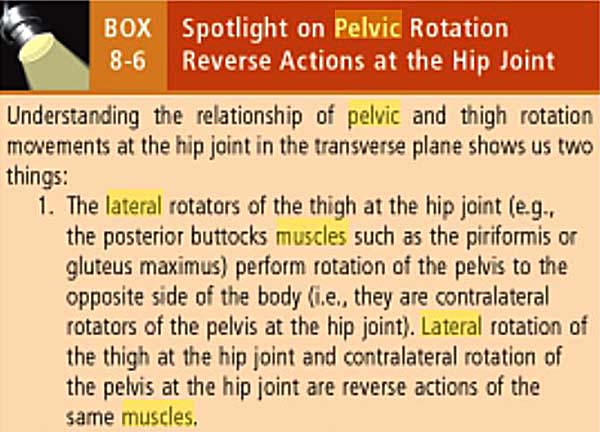

When the 6 right-sided lateral pelvic rotator muscles are stretched at the end-backswing position, they are ready to contract during the early downswing. If they contract and shorten (thereby decreasing the distance between their points of origin and their points of insertion) they can cause external rotation of the right femur in the right hip joint if the pelvis is stabilised or a counterclockwise rotation of the pelvis away from the right femur if the right femur is stabilised. This is a critical point that one needs to fully understand - so I will discuss this issue in greater detail.

I stated that if

Here is a

link to pages from the online version of that textbook.

Read pages 277- 279.

If you decide not to read those pages, here are the relevant sections in an excerpted form.

Note that the author states that the lateral pelvic rotator muscles can cause lateral (external) rotation of the thigh at the level of the hip joint and also a contralateral rotation of the pelvis at the hip joint, and that these two motions are merely reverse actions of the same muscles.

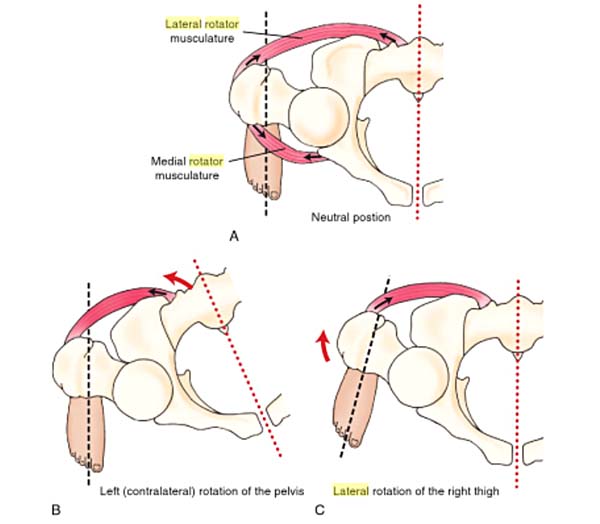

Now, consider those differential (reverse) actions in diagrammatic form.

Diagram A shows the pelvis and ipsilateral femur in a neutral position.

The black arrows shows that if the muscles contract and shorten, that

they will cause the muscle's origin (on the pelvis or sacrum) and

the muscle's insertion (on the upper femur) to move closer towards each

other. Diagram B shows that if the right femur is "stabilised" that contraction

of the right-sided lateral pelvic rotator muscles will cause the pelvis to

rotate counterclockwise away from the "stabilised" right femur. Diagram C shows

that if the pelvis is "stabilised" that contraction of the right-sided lateral

pelvic rotator muscles will cause the right femur to laterally (externally)

rotate in the right hip joint. I believe that diagram B is very applicable to

the right hip joint/femur between P4 and P4.5 if weight-pressure loading of the right leg (due to the golfer

actively pushing down into the ground under the right foot) causes the right

leg to become "stabilised". At the end-backswing position, a pro golfer

has roughly 70-80% of his overall COP-measurement under his right foot and if he

maintains, or even slightly increases, his degree of weight-pressure loading of

his right leg/foot at the start of the early downswing, he can very effectively

stabilise the position of the right femur is space. Then, when the right-sided

lateral pelvic rotator muscles contract, they will cause a counterclockwise

rotation of the pelvis away from the "stabilised" right femur.

Consider a similar type of scenario from my video presentation - featuring the contraction of the triceps muscle that causes the elbow joint to straighten (extend).

Capture images from my video presentation.

In images 1 and 2, I am demonstrating how contraction of the right triceps

muscle causes straightening (extension) of the right elbow. In image 1, I had

previously contracted my right biceps muscle to flex my right elbow, while

simultaneously stretching my passively relaxed right triceps muscle, and that

particular muscle action brought my right hand closer to my right shoulder

socket.

In image 2, I contracted (and shortened) the right triceps muscle and that caused my right hand to move further away from my right shoulder socket as my right elbow straightened (extended). Why did my right hand move away from the right shoulder socket, rather than my right shoulder socket move away from my right hand? The answer is obvious - the biomechanical resistance (impedance) that my right hand presents to any move away from the right shoulder socket is far less than the biomechanical resistance (impedance) that my right shoulder socket (and the conjoined upper torso) presents to any move away from my right hand because my right hand is freely mobile in space and it can be easily moved (with very little triceps muscle contractile force required to straighten my right elbow).

Now, consider a scenario where I am positioned closer to the wall with the base of the palm of my right hand barely touching the wall - see image 3.

When I contract my right triceps muscle, it cannot cause my right hand to move further away from my right shoulder socket because the wall offers too much resistance (impedance). Therefore, an isotonic contraction of my right triceps muscle will cause my right shoulder socket (and conjoined upper torso) to move away from my right hand, which can be deemed to be "stabilised" by the presence of the wall resisting any push-force that is being applied against the wall - see image 4. As the right triceps muscle starts to isometrically contract it will start to generate a muscle-derived "action force" that pushes my right palm against the wall with a progessively increasing force, and that will produce a sensory "feeling of pressure" being felt under the base of my right palm where it abuts against the wall. That "feeling of pressure" will increase until the right triceps muscle has produced enough isometric contractile force to move the right shoulder socket (and my conjoined upper torso) away from my "stabilised" right hand. When my right elbow eventually straightens due to the isotonic contraction of my right triceps muscle, I will "feel" progressively less pressure-sensation under the base of my right palm where it abuts against the wall. It is important to realize that the wall is not the primary causal agent that is causally producing the "feeling of pressure" under my right palm and any pressure-sensation that I experience under my right palm is primarily due to an "action force" involving a muscular contraction of the right triceps muscle, and the "reaction force" is secondarily produced by the wall resisting any push-force produced by my right palm against the wall. From a "cause-and-effect" perspective, it is the contraction of my right triceps muscle that is the inciting causal agent that secondarily generates a Newtonian type of "reaction force" due to the wall resisting any push-force being applied by the palm of my right hand against the wall.

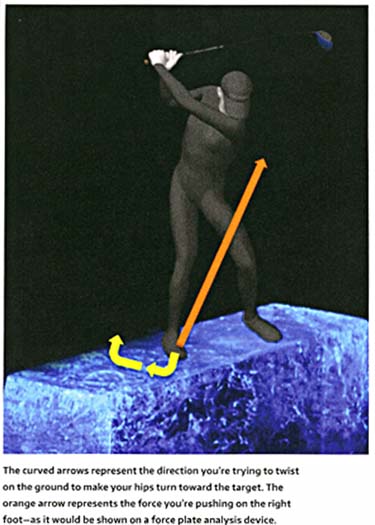

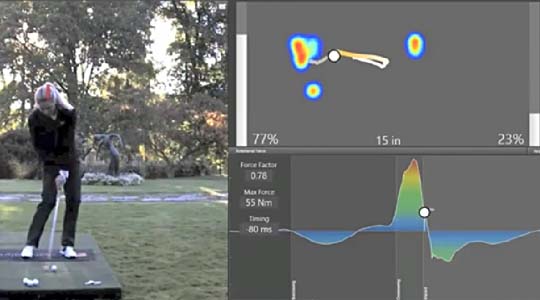

So, getting back to the start of the downswing where a pro golfer "stabilises" his right leg/foot by pressing down into the ground, an "action force" is being directed vertically downwards secondary to the contraction of muscles in the muscle zone of the right lower limb and right pelvic girdle, and that "action force" causes the right foot to move more firmly against the ground, while the "reaction force" is provided by the ground resisting the push-force exerted by the right foot against the ground. There is yet another "action force" and another "reaction' force" operant at the start of the downswing between P4 and P4.5 and those "forces" are shear forces operating in the horizontal plane under the right foot. If a professional golfer is analysed using force plate technology, that can measure both vertical and horizontal pressure-shear forces under the right foot at the start of the downswing, the force-pressure measurements in the horizontal plane are found to be directed clockwise under the right foot. It is as if the golfer is twisting his right foot clockwise (away from the target) against the resistance of the ground. What causes those shear forces to be detectably present under the right foot in the early downswing? I believe that they are likely to be secondary to the contraction of the right-sided lateral pelvic rotator muscles that attempt to rotate the right femur externally in the right hip joint. However, the pro golfer is resisting any rotary motion of his right femur by pushing downwards into the ground while simultaneously, but unconciously, twisting his right foot clockwise against the resistance of the ground. That muscle action (involving right-sided muscles of the right lower limb and lower body) "stabilises" the right leg/foot against the resistance of the ground and eventually results in the pelvis rotating away from the "stabilised" right leg/foot when the right-sided lateral pelvic rotator muscles start to isotonically contract. As the pelvis rotates counterclockwise away from the "stabilised" right leg/foot, the shear force measurement under the right foot will automatically/naturally decrease. The peak time period of the shear force, and the maximum amount of "shear force", experienced under the right foot will be measured just before the right-sided lateral pelvic rotator muscles start to isotonically contract (shorten) thereby rotating the pelvis away from the weight-pressure loaded right leg/foot and they will be maximally present when the right-sided lateral pelvic rotator muscles are generating their maximal amount of isometric contractile force. It is important to realise (from a causal perspective) that the "action force" is generated by the right-sided lateral pelvic rotator muscles and that the clockwise twisting shear force measured under the right foot (by a force-pressure plate) is secondarily due to a "reaction force" caused by the ground resisting any twisting of the right foot in a clockwise direction. From a "cause-and-effect" perspective, I think that it would be *incorrect to surmise that the simple biomechanical maneuver of twisting the right foot clockwise against the ground will cause the pelvis to rotate counterclockwise - if the right-sided lateral pelvic rotator muscles are not active.

(* I think that many golf instructors/ golfers get this "cause-and-effect" biomechanical relationship mixed-up and they incorrectly believe that the simple action of twisting the right foot clockwise against the resistance of the ground will cause ["trigger"] the pelvis to rotate counterclockwise, and they are totally unaware of the primary role of the right-sided lateral pelvic rotator muscles in this "cause-and-effect" scenario).

What role do the left-sided lateral pelvic rotator muscles play in rotating the pelvis counterclockwise during the P4 => P5 time period?

Consider the situation of the left hip joint at the end-backswing position if a golfer lifts his left heel during the backswing action and allows his left femur to be less externally rotated in the left hip joint (compared to the address position).

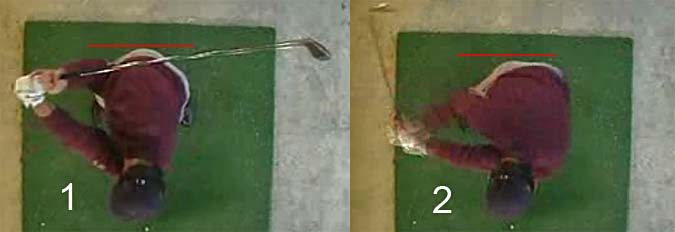

Capture images of Arnold Palmer from a swing video.

Image 1 shows Arnold Palmer at his end-backswing position. Note that his left knee is very close to his right knee due to the fact that he has adducted and internally rotated his left femur during his backswing action between P1 => P4. Note how much he has lifted his left heel off the ground, and that allows him to have a bent left knee at the P4 position with his left knee "pointing" at a spot behind the ball. Under those end-backswing conditions, the left-sided lateral pelvic rotator muscles are more passively stretched and ready to contract. Note that I have drawn a blue line against the inside of his left lower thigh/knee at his end-backswing position.

Image 2 shows his first move at the initiation of the downswing - which is a move of his left knee towards the target. Note that the targetwards motion of his left knee happens even before his pelvis seemingly starts to rotate counterclockwise. What causes his left knee to move targetwards? I believe that it due to activation of his left-sided lateral pelvic rotator muscles that externally rotate and abduct his left femur in his left hip joint. Why does activation of the left-sided lateral pelvic rotator muscles cause the left femur to externally rotate, rather than cause the pelvis to rotate clockwise away from the left femur? I believe that it is due to the fact that his left leg/foot is not weight-pressure loaded at his end-backswing position, which means that there is little impedance/resistance to external rotation of the left femoral head in the left hip joint when the left-sided lateral pelvic rotator muscles contract.

Note that his pelvis starts to rotate counterclockwise in images 3, 4 and 5 while his left knee continues to move targetwards. By the time he gets to the end of his hip-squaring phase (image 5), note that both thighs are are in a state of dual-external rotation in their respective hip joints.

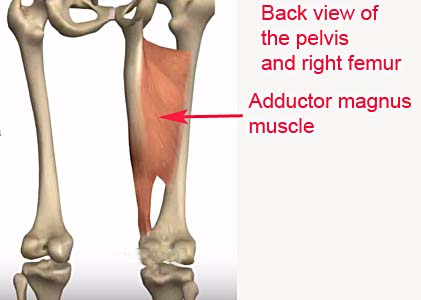

Note how much his left knee has moved targetwards between image 1 => image 5 due to external rotation and abduction of his left femur in his left hip joint. However, that counterclockwise rotation of his left femur in his left hip joint - due to activation of his left-sided lateral pelvic rotator muscles - should theoretically not cause his pelvis to rotate counterclockwise. Nonetheless, there is another biomechanical action that is likely in play during the early downswing that enables the externally rotating left femur to assist in the counterclockwise rotation of the pelvis during the early downswing - and that biomechanical action is due to the simultaneous muscular contraction of the left adductor magnus muscle.

There has only been one electromyography study performed by golf researchers on pelvic girdle area muscles during a golf swing and that is the study by Bechler et al [1]. In that study, the golf researchers found that the lead adductor magnus muscle is very active during the early-mid downswing.

The adductor magnus muscle is the largest of the thigh adductor group of muscles and it has its origin on the inferior pubic ramus and it inserts on the medial (inner) surface of the lower-mid femur.

Here is a you-tube video showing the muscles in the medial compartment of the thigh - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ecfssWS1aVg

Here are capture images from the video showing the adductor magnus muscle.

Anterior (front) view

Note that I have yellow-highlighted the left adductor magnus muscle in that

image.

Posterior (back) view

During the early downswing between P4 and P5, the left femur is being externally

rotated due to contraction of the left-sided lateral pelvic rotator muscles so

that the left thigh becomes increasingly externally rotated at P5

(relative to the scenario at P4). However, if the the left adductor magnus is also isometrically active during this early

downswing time

period, it can pull the left inferior pubic ramus towards the left thigh (as it is being externally rotated),

thereby contributing to the counterclockwise rotation of the pelvis (which is

mainly due to contraction of the right-sided lateral pelvic rotator muscles). I

don't know how much the lead adductor magnus muscle contributes to the

counterclockwise rotation of the pelvis during the early downswing - compared to

the contribution from the right-sided lateral pelvic rotator muscles - but it

may play a significant role.

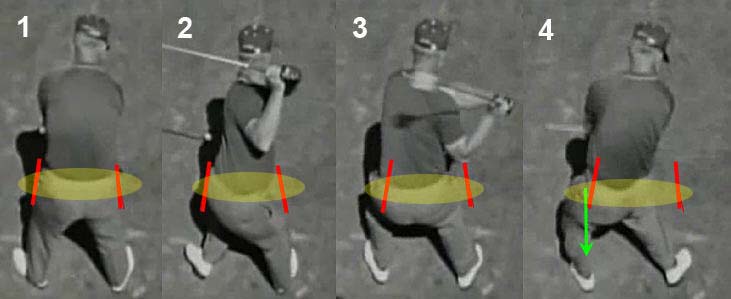

Now, consider another biomechanical phenomenon that is frequently (but not always) seen in professional golfers during the early downswing between P4 and P5 - and that biomechanical phenomenon is the increased degree of flexion happening at the level of the hip joints and knee joints.

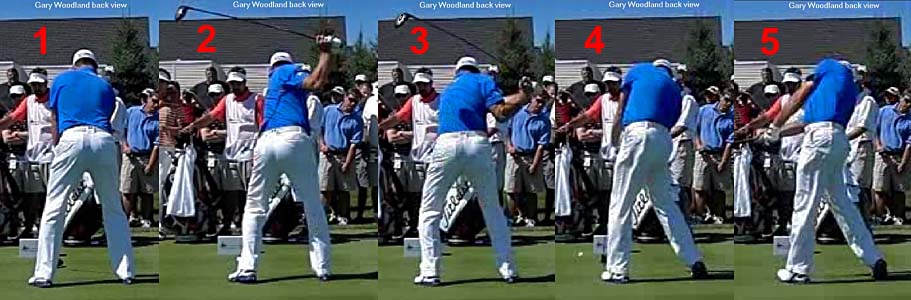

Consider yet again these back-view images of Jamie Sadlowski's downswing action.

Image 1 shows Jamie Sadlowski at his end-backswing position - note that he has a

certain amount of flexion of his right hip joint and right knee joint.

Image 2 shows Jamie Sadlowski at the P4.5 position - note that he has an increased degree of flexion at the level of his right hip joint and right knee joint, and that causes his head to drop a few inches during his early downswing.

What is the relevance of this increased degree of hip joint and knee flexion that happens during the early downswing?

The first relevant benefit of increasing the degree of flexion of the right hip joint and right knee joint at the start of the transition to the downswing is that it allows a golfer to increasingly weight-pressure load, and thereby increasingly "stabilise", the right femur in space - so that the pelvis can be induced to more efficiently rotate counterclockwise AWAY from the increasingly "stabilised" right leg during the early downswing when the right-sided lateral pelvic rotator muscles contract (shorten).

The second benefit derived from increasing the degree of flexion at the level of the right hip joint is that it helps to ensure that the right femur externally rotates, and doesn't internally rotate, at the start of the downswing. Many unskilled amateur golfers start their downswing by "kicking-in" their right knee towards the ball and that biomechanical action would induce an adduction and internal rotation of the right femur. By contrast, most professional golfers keep their right femur externally rotated and slightly abducted during the early downswing's P4 => P5 time period, so that they acquire the Sam Snead "sit-down" look by the end of the early downswing (where both femur's are externally rotated in their respective hip joints by roughly the same amount).

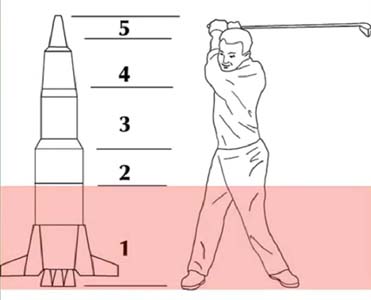

Here is a diagrammatic image of Sam Snead as he gets near the P5 position (end of the hip-squaring phase).

Note that he looks like he is "squatting" and that both thighs are externally

rotated to the same degree - giving him the classic (prototypical) Sam Snead

"sit-down" look (as if he were starting to sit down on a bar stool).

Consider Jamie Sadlowski at the end of his hip-squaring phase.

Note that Jamie Sadlowski also has that "squatting" look at the end of his hip-squaring phase (image 5) where both femur's are externally rotated to roughly the same degree with respect to their respective hip joints, and he also prototypically manifests the Sam Snead "sit-down" look.

Note how much his head has dropped between his P4 position (image 1) and his P5 position (image 5), and note that it is primarily due to increased flexion at the level of his hip joints.

I previously stated that the second benefit derived from increasing the degree of flexion at the level of the right hip joint is that it helps to ensure that the right femur externally rotates, and doesn't internally rotate, at the start of the downswing. What is the underlying/explanatory biomechanical mechanism?

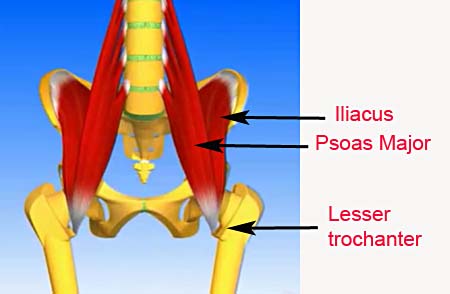

Consider the main pelvic girdle muscles that are causally responsible for increasing the degree of right hip joint flexion during the early downswing - the iliopsoas muscle (which is actually due to the combination of the iliacus muscle and the psoas major muscle).

Note that the psoas major muscle has its origin on the lateral side of the upper

four lumbar vertebra while the iliacus muscle has its origin on the inner

surface of the iliac fossa. Both of those muscles join together to form a

conjoined tendon that inserts at the inner (medial) surface of the lesser

trochanter.

When the iliopsoas muscle contracts it shortens the distance between the lesser trochanter and the points of origin of the two muscles thereby causing increased flexion at the level of the ipsilateral hip joint.

However, because the point of insertion of the conjoined tendon at the lesser trochanter is on the inner (medial) side of the upper femur, it also causes external rotation of the ipsilateral femur when the iliopsoas muscle contracts - as demonstrated in the following image.

Note that when the right iliopsoas muscle contracts (see yellow arrow) it flexes the right thigh at the level of the right hip joint. However, note that it also simultaneously causes external rotation of the right femur (see curved white arrow, which demonstrates the counterclockwise rotation of the right femur).

That helps to explain why a skilled professional golfer

can routinely have his right femur in a state of external rotation at the level

of the right hip joint at the end of the hip-squaring phase - because the

external rotary torquing action of the right iliopsoas muscle supplements the

external rotary torquing action of the right-sided lateral pelvic rotator

muscles, which obviously promotes a state of external rotation of the right femur

in the right hip joint when the pelvis rotates counterclockwise

away from a "stabilised" right femur and "stabilised" right

foot (that is being torqued clockwise against the resistance of the ground due

to the external rotary torquing force). It is easy to understand

why the left femur is externally rotated at the end of the hip-squaring phase

because it is causally due to the contraction of the left-sided lateral pelvic

rotator muscles that externally rotate the left femoral head in the left hip

joint during the P4 => P5 time period. Remember that the left leg is not

weight-pressure loaded between P4 and P5, and only 20-30% of the overall

COP-measurement is located under the left foot at P4 and approximately 50% at P5

(which is the end of the hip-squaring phase). Therefore, there is no significant

impedance/resistance to external rotation of the left femur in the left hip

joint and it is biomechanically easy to ensure that the left femur is externally

rotated at the end of the hip-squaring phase.

Biomechanics of the pelvic motion in the mid-late

downswing between the P5 position and the P7 position (impact)

During the early downswing, the pelvis rotates about ~50 degrees counterclockwise (on average) and during that time period the pelvic crest remains roughly level relative to the ground, which means that the pelvis mainly rotates horizontally during the hip squaring phase.

During the mid-late downswing, the pelvis rotates another ~40 degrees counterclockwise (on average) which means that the pelvis would be ~40 degrees open at impact. Another biomechanical phenomenon that happens in the mid-late downswing is that the left pelvis elevates, so that it is higher than the right pelvis at impact.

Consider the muscle actions that are responsible for the horizontal and vertical motion of the pelvis during the mid-late downswing.

By the end of the hip-squaring phase, the lateral pelvic rotator muscles are significantly contracted (shortened) and they can no longer play a significant role in rotating the pelvis counterclockwise during the mid-late downswing. So, a relevant question arises-: Which muscles cause another 40 degrees of counterclockwise rotation of the pelvis during the 2nd phase of the "left hip clearing action" (during which time period the left hip joint moves increasingly towards the tush line in a counterclockwise rotary manner)? I believe that a few major muscles play an important role in causing the continued counterclockwise rotation of the pelvis during the mid-late downswing - the i) left knee extensors and ii) the left gluteus maximus muscle and the iii) left adductor magnus muscle.

Consider my biomechanical explanation.

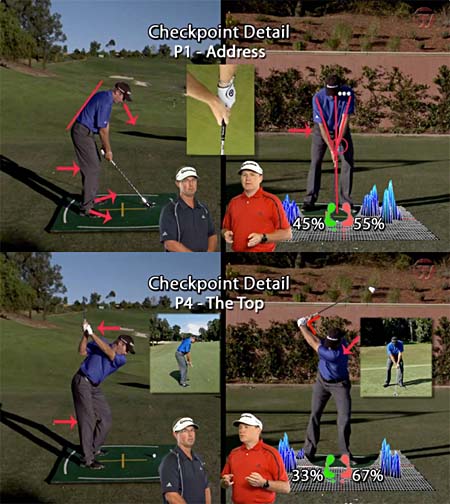

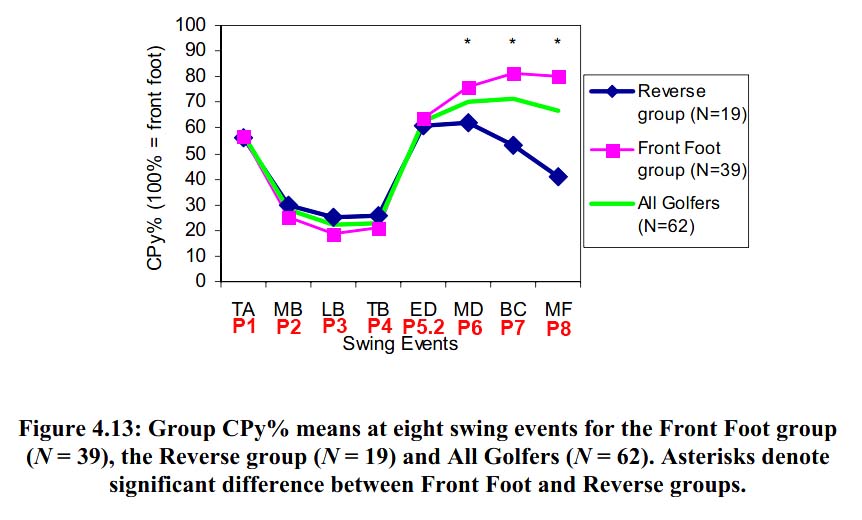

A characteristic feature of a skilled professional golfer's late downswing action is the "fact" that the left leg progressively straightens due to extension at the level of both the left hip joint and the left knee joint while the left foot becomes increasingly weight-pressure loaded. At the P5 position (end of the hip-squaring phase) approximately 50% of the overall COP-measurement is located under the left foot, and this amount increases to approximately 80% of the overall COP-measurement by the P7 position (impact) in golfers (who are classified as "front foot" golfers).

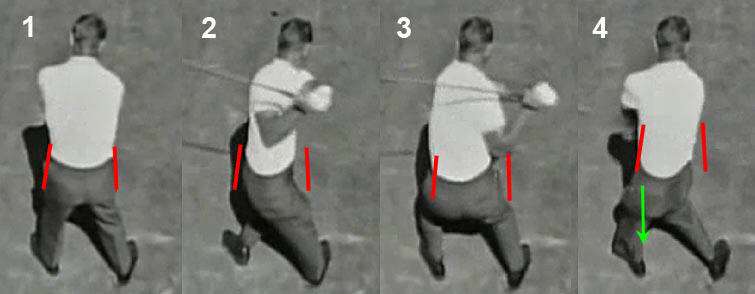

Consider the implications of that "fact" by considering Ben Hogan's late downswing action (from a left back-viewing perspective).

Image 1 shows Ben Hogan at his end-backswing position and image 2 shows Ben

Hogan at the P5 position (end of the hip-squaring phase). Note that he manifests

the Sam Snead "sit-down" look at the P5 position - manifesting a significant amount of flexion at the

level of his left hip joint and left knee joint. Note that he pulled his left

buttocks back towards the tush line during his early downswing, and that

represents phase 1 of the "left hip clearing" action.

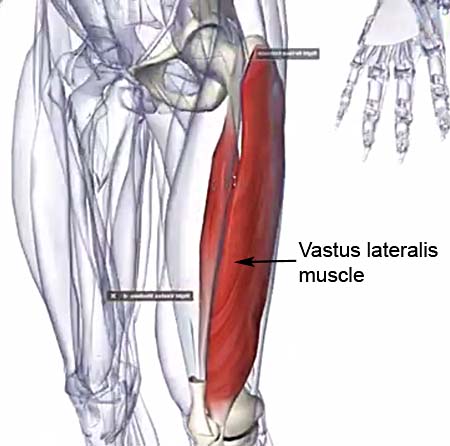

Image 4 shows Ben Hogan at impact. Note that his pelvis is about 40 degrees open at impact, which means that he rotated his pelvis another ~40 degrees counterclockwise during phase 2 of his "left hip clearing" action. A major factor that causes the left femoral head (and therefore the left hip joint) to move further back towards, and eventually back beyond, the tush line (and also more counterclockwise away from the target) during phase 2 of the "left hip clearing" action is the fact that the left leg is straightening, which means that the distance from the left foot to the left hip joint must increase. Because the left foot is solidly grounded during the later downswing as it is increasingly weight-pressure loaded (due to the fact that the COP-measurement under the left foot increases from 50% of the overall COP-measurment at P5 to 80% of the overall COP-measurement at impact), that means that the left femoral head (and therefore left hip joint) must move further away from the left foot and closer to the tush line during the left leg straightening action. Note how Ben Hogan's left knee becomes straightened (extended) at impact and that is due to the contraction of the left knee extensor muscles (especially the vastus lateralis muscle).

The left vastus lateralis muscle forms a large part of the left

quadriceps muscle group in the anterior compartment of the left thigh and when

it contracts it extends the left knee, and it also braces the left knee so that

it doesn't buckle/bend sideways (as evidenced in image 4 of the Ben Hogan downswing

series of capture images).

Another biomechanical factor that contributes to the continued counterclockwise rotation of the pelvis in the later downswing is the fact that the left adductor magnus muscle is still actively contracting and it pulls the left inferior pubic ramus (and therefore the left side of the lower pelvis) closer to the left femur. During the later downswing, the pelvis rotates counterclockwise more than the left femur, so that the left femur becomes progressively more internally rotated in the left hip joint, and isotonic contraction of the left adductor magnus muscle is continuously pulling the left femur and the left-lower pelvis closer together during this time period.

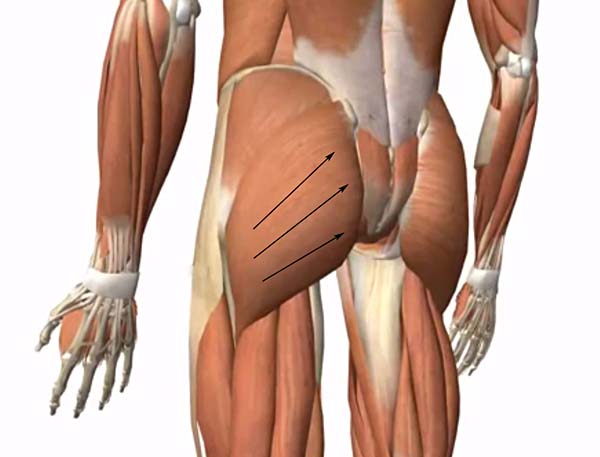

Also, note that Ben Hogan's left hip joint doesn't only move away from the ball-target

line, and therefore closer to the tush line, as he nears impact, it also moves

away from the target, and that is partly due to the active contraction of the left

gluteus maximus muscle.

The muscle lying under the black arrows is the left gluteus maximus

muscle, and it is attached medially (at its origin) to the outer (lateral) left edge of the sacrum and

to a significant section of the posterior pelvic crest and it inserts at the back of the upper

left femur. When that muscle contracts (and shortens in the direction of the

black arrows) it pulls the left upper femur towards the sacrum (midline) and

thereby contributes to the counterclockwise rotation of the left hip joint

away from the target as the left hip joint extends - see images 4 and 5

of the Ben Hogan downswing series of capture images.

During the impact and early followthrough time period, one often notes that a pro golfer's left femur externally rotates to a variable degree and that is also due to the continued isotonic contraction of the left gluteus maximus muscle. The reason why contraction of the left gluteus maximus muscle causes external rotation of the left femur, as well as extension of the left femur in the left hip joint, is the "fact" that the gluteus maximus muscle's point of insertion on the back of the left upper femur is on the outer (lateral) side of the center of the back of the left femur. The degree of external rotation of the left femur varies considerably in different professional golfers, and I will discuss the biomechanical factors that affect the magnitude of this biomechanical phenomenon in greater detail later in this review paper.

More information on the biomechanics of the downswing's pelvic motion -

presented in a Q&A format

Question number 1:

Can you offer swing tips (swing thoughts) that can usefully promote the acquisition of a pro golfer's type of rotary pelvic motion (rather than a hip spinning type of rotary pelvic motion) in a student golfer, and can you describe which swing thoughts are potentially harmful because they can predispose to excessive hip spinning or too much left-lateral shift of the pelvis?

Answer:

I realise that providing a significant amount of background information on golf swing biomechanics is not necessarily helpful to golfers who are not deeply analytical, and I realise that they would prefer more practical swing tips (swing thoughts). So, here is some practical advice that may help a student golfer perform a pro golfer's type of rotary pelvic motion - rather than a hip spinning type of rotary pelvic motion.

I think that a student golfer needs to adopt two swing thoughts at the start of his downswing if wants to learn how to efficiently perform a pro golfer's type of rotary pelvic motion during phase 1 of the "left hip clearing" action - i) maintain, or even momentarily increase, a high degree of weight-pressure loading of the right leg/foot so that the right leg can be "stabilised" - while the isotonic contraction of the right-sided lateral pelvic rotator muscles (that happens subconsciously) causes the pelvis to rotate counterclockwise away from the "stabilised" right leg/foot; and ii) perform the "left hip clearing" action as described by Ben Hogan in his golf instructional book [2] where one basically rotates the left buttocks back towards the tush line in a counterclockwise rotary manner.

Consider the famous diagram from Ben Hogan's book [2].

In that diagram, Ben Hogan has a stretched elastic band drawn between the front

of his left pelvis and a wall behind him at his end-backswing position. Then, at

the start of the downswing, he "feels" that the left hip joint area of his left

pelvis is being pulled back towards the tush line in a counterclockwise rotary

manner as the stretched elastic band contracts (shortens). In other words, the

key swing thought for a student-golfer should be the swing thought of "rotating" the left

pelvis back towards the tush line in a counterclockwise rotary manner so that

the pelvis can become square by the end of the early downswing (P5 position).

The simple swing thought of "rotating" the pelvis counterclockwise (as described)

should subconsciously cause a contraction of both the right-sided and left-sided

lateral pelvic rotator muscles, which in tandem should produce the pro golfer's

type of rotary pelvic motion. A student-golfer may think that he needs to

consciously activate the right-sided lateral pelvic contractor

muscles in order to induce a counterclockwise rotation of the pelvis away from a

weight-pressure loaded, and therefore "stabilised", right leg/foot, but I do not

believe that it is necessary. The human brain automatically/naturally knows that

it needs to activate the right-sided lateral pelvic rotator muscles if a

decision is made to rotate the pelvis counterclockwise by "rotating" the left

side of the pelvis back towards the tush line. However, it is

biomechanically necessary that the golfer "stabilise" the right femur/leg and

simultaneously ensure that the right foot is solidly grounded against the

resistance of the ground so that the ground can absorb any clockwise torque of

the right foot. A golfer, who is physically capable of generating a lot of

counterclockwise rotary torque of the pelvis, must ensure that he has

spikes/cleats under his right golf shoe that can prevent slippage of the right

foot if he wants to guarantee that the right foot is adequately "stabilised"

during phase 1 of the "left hip clearing" action.

Under conditions of adequate "stability" of the right leg/foot, the pelvis will

automatically/naturally rotate counterclockwise away from the

"stabilised" right leg/foot when the right-sided lateral pelvic rotator muscles

contract, even though the golfer may actually have the "feeling" that he is

"pulling" the left buttocks back towards the tush line. A golfer may also "feel"

his right ankle invert and "feel" and that he is rolling his right foot inwards,

but that experiental biomechanical phenomenon is secondary to

the counterclockwise motion of the pelvis +/- a small degree of targetwards

motion of the right femoral head and right knee that may happen simultaneously

during this early downswing time period if there is a significant amount of

left-lateral shift of the pelvis happening during phase 1 of the "left hip

clearing" action. It is very important that a student-golfer realise that any

"feeling" of his right foot rolling inwards (if it happens) should be a passive "feeling", and

not an active/deliberate action.

I think that there should be no swing thought relating to the right side (right pelvis or right leg/foot) where one thinks of activating the right side of the pelvis in a "pushing" or "thrusting" manner and/or activating the right knee/foot in an active "pushing-away" motion as this may predispose to hip spinning or too much left-lateral pelvic shift (pelvic sliding). In other words, I think that a student-golfer shouldn't think of actively pushing off the inside of the right foot in a targetwards direction, or think of "kicking-in" the right knee towards the ball, or think of isotonically activating the right gluteus maximus muscle because that may induce the right buttocks to prematurely leave the tush line in a hip spinning manner. I think that the most useful swing thought that pertains to the right leg/foot at the start of the downswing should be the "feeling" of stabilising the right leg/foot by maintaining (or even momentarily increasing) the high degree of weight-presure loading of the right foot +/- experiencing the "feeling" of twisting the right foot clockwise solidly against the resistance of the ground. A student-golfer may never even consciously sense the "feeling" of the right foot being twisted clockwise against the resistance of the ground because it is really a reactive phenomenon, that is secondary to the contraction of the right-sided lateral pelvic rotator muscles (which happens subconsciously). If a student golfer consciously tries to twist the right foot clockwise against the resistance of the ground as an "active action", then he is deliberately trying to create an "active ground reaction force" that may predispose to a right hip spinning type of pelvic rotary motion.

Some golf instructors advise their student-golfers to actively twist their right foot clockwise against the resistance of the ground in order to trigger a counterclockwise rotary pelvic motion.

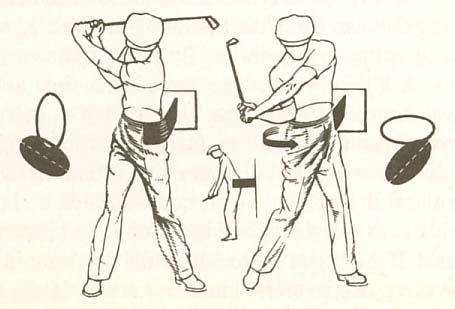

Consider an example - by Michael Jacobs [3].

Image copied from reference number [3]

The text in that image states that a golfer must think of twisting the right

foot clockwise against the resistance of the ground (represented by the yellow

arrows) in order to create a ground reaction force that is directed in the

direction of the orange arrow, and Michael Jacobs believes that this ground

reactive force will make the pelvis rotate counterclockwise

around the center-of-rotation (COM) of the body (according to Newtonian

principles of motion). This "belief" comes directly from Dr. Young-Hoo Kwon, who

promotes a *theory that the counterclockwise rotation of the pelvis during the

downswing is due to ground reactive forces acting on the center-of-rotation

(COM) of the body via the Newtonian physical mechanism of a moment force and a

moment arm.

( * I have no sympathy for Dr. Kwon's Newtonian-based theory and I may write a critical review paper comparing his physical-based theory to my biomechanics-based theory, that is based on well-established/sound principles of golf swing biomechanics and kinesiology).

Here is the text from Michael Jacobs' book [3] that accompanies this image-: "Suspend reality for a second and imagine you're standing on a sheet of ice. Without using a ball get in your normal stance. Now, make a slow backswing, and as your body gets close to the end of its turn away from the ball, feel it slow down even more while at the same time push with your right (trailing) foot as though you are trying to spin it away from the target. With your foot flat on the ground and spikes on, it won't actually spin out, but the pressure you are creating will trigger your hips to translate and turn in the opposite direction - toward the target".

Note that Michael Jacobs' bold-highlighted text claims that the pressure that a golfer is creating under the right foot (when he twists his right foot clockwise against the resistance of the ground) will trigger the pelvis to rotate counterclockwise (according to Newtonian principles of motion). I personally believe that he is mixing up "cause-and-effect" because I believe that the true "cause" of the counterclockwise rotation of the pelvis at the start of the downswing in a skilled professional golfer (who executes the pro golfer pattern of pelvic motion) is due to the muscular contraction of the right-sided lateral pelvic rotator muscles, and that any twisting pressure-sensation experienced under the right foot in a clockwise direction during that time period is an "effect" due to the contraction of the right-sided lateral pelvic rotator muscles attempting to externally rotate the right femur/leg against the resistance of the ground while the right leg/foot is being "stabilised" by the golfer actively weight-pressure loading the right leg/foot.

Consider the perspective of another golf instructor - Brian Manzella - who has also been influenced by Dr. Young-Hoo Kwon's ideas on ground reaction forces.

Here is link to a Brian Manzella video lesson (relating to his personal interpretation of Adam Scott's golf swing)

http://www.golf.com/video/learn-adam-scotts-secret-power-move

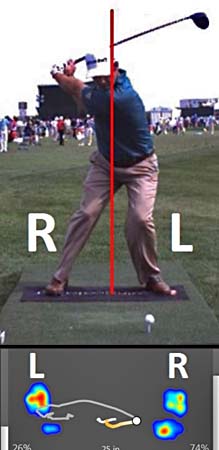

Here are capture images from his video.

Image 1 shows Brian Manzella at the mid-backswing position. In the video lesson,

he states that a golfer should think of getting his center-of-pressure (COP)

over to his right foot, so that by the time he gets his clubshaft parallel to

the ground he already has 70% of his overall COP-measurement under his right

foot.

Then, Brian Manzella states that a golfer should push upwards in the direction of his right ear to "get force into one's backswing". I think that his assertion that a golfer should push up towards his right ear makes no sense from a biomechanical perspective because it will only predispose to an exaggerated use of an arch-extension maneuver that may predispose to a loss of one's spine bend inclination angle as the right side of the mid-upper body extends or it may even predispose to reverse pivoting (as seen in image 2). Adam Scott obviously doesn't suffer from either a loss of his spine bend inclination angle (or reverse pivoting) in his backswing action. I suspect that Adam Scott is progressively increasing his COP measurement under his right foot from ~50% of his overall COP-measurement at address to 70-80% of his overall COP-measurement by his end-backswing position. By increasingly weight-pressure loading his right leg/foot during his backswing action, he can prevent any swaying motion of his right leg/pelvis away from the target during his backswing action. I also don't think that Adam Scott is actually pushing upwards from his right foot in the direction of his right ear (as Brian Manzella claims) and I think that he is basically pushing his right foot downwards into the ground as he progressively weight-pressure loads his right leg during his backswing action, and that will allow him to efficiently "stabilise" his right leg during both his backswing action and also at the critical transitional moment when he transitions to the start of his downswing action.

To start the downswing, Brian Manzella states that a golfer should push off the right foot in order to move the ground force vector (which was previously directed towards the right ear) to a direction that is left of the left ear so that the changing ground force vector can cause the lower body to rotate around the body's center-of-rotation (COM) and he states that when the left arm is parallel to the ground (image 3) that a golfer should have 70% of his overall COP-measurement already under his left foot. Then, he states that from the P5 position (image 3) to impact, that a golfer should only push upwards towards his left ear, which will secondarily cause a straightening of his left leg (as seen in image 4).

In other words, Brian Manzella thinks that the changing ground reaction forces generated under the two feet are causing Adam Scott's rotary pelvic motion during his downswing and that it is also causing the straightening of his left leg as he pushes upwards towards his left ear from his weight-pressure loaded left foot in his later downswing. I totally disagree with his explanation, and I think that Brian Manzella is simply imposing his Dr. Kwon-derived explanatory theory on Adam Scott's swing. I think that my biomechanical explanation better explains Adam Scott's downswing action. I think that Adam Scott starts his downswing's rotary pelvic motion by activating his right-sided lateral pelvic rotator muscles (while weight-pressure loading his right leg/foot, which will "stabilise" his right femur so that his pelvis can rotate counterclockwise away from his "stabilised" right leg) and that biomechanical muscular action will get his pelvis square by the P5 position, where he will likely have 50% of his overall COP-measurement under each foot. Adam Scott will then straighten his left leg in his later downswing secondary to the activation of his left knee extensor muscles and that will cause elevation of his left pelvis as the left hip joint moves further away from his solidly grounded left foot (which probably has 70-80% of his overall COP-measurement located under his left foot at impact because Adam Scott manifests the swing biomechanics of a * "front foot" golfer).

(* I will explain the different swing biomechanics between a "front foot" golfer and a "reverse foot" golfer later in this review paper)

I don't think that Adam Scott is actively pushing off his right foot at the start of his downswing to any significant degree in either a targetwards direction (that can predispose to excessive pelvic sliding) or in a direction that is more outwards towards the ball that can predispose to hip spinning.

Here are capture images from a DTL video of Adam Scott's driver swing.

Imag 1 shows Adam Scott at his end-backswing position. I have drawn a red line

against the back of his right buttocks and that represents his tush line.

Image 2 shows Adam Scott at the P4.5 position. Note that he is rotating his left buttocks back towards the tush line in a hip-squaring manner (as described by Ben Hogan in his "left hip clearing" action diagram) while still keeping his right buttocks back against the tush line.

Image 3 shows Adam Scott at the P5 position with a square pelvis. Note that his right buttocks is still against the tush line, which means that he is not a right hip spinner.

Image 4 shows Adam Scott at the P5.5 position. Note that his right buttocks is now leaving the tush line and that his pelvis is slightly open. However, note that he can get easily his right elbow well in front of his right hip area by P5.5 and that his right elbow is not being "blocked" by his right pelvis. Note that his right heel is not elevated off the ground and note that his right knee is not "kicked-in".

Now consider Rory McIlroy's pelvic motion during the early-mid downswing.

Here are capture images from a DTL swing video of Rory McIlroy's driver swing.

Image 1 shows Rory McIlroy at his end-backswing position. I have drawn a red

line against the back of his right buttocks and that represents his tush line.

Image 2 shows Rory McIlroy at the P4.5 position. Note that he is rotating his left buttocks back towards the tush line in a hip-squaring manner (as described by Ben Hogan in his "left hip clearing" action diagram) while still keeping his right buttocks back against the tush line. Note that Rory McIlroy manifests far more knee and hip joint flexion than Adam Scott at the start of his downswing.

Image 3 is at the P5 position. Note that Rory McIlroy has got his pelvis more than slightly square and note that his right buttocks is already starting to leave the tush line, which indicates that he has an element of a right hip spinning action.

Image 4 is at the P5.5 position. Note that Rory McIlroy's pelvis is more open than Adam Scott's pelvis at his P5.5 position. Note that his right buttocks is well forward of his tush line, and that he has elevated his right heel and kicked-in his right knee towards the ball - and those biomechanical features are suggestive of a small degree of right hip spinning. Note that the forward-and-outward motion of his right pelvis (due to an element of right hip spinning) gives him less room in front of his right hip area to position his right elbow, and that his right elbow is therefore positioned more alongside his right hip area. That biomechanical phenomenon where the right pelvis is potentially "blocking" the right elbow's path is a well known side-effect of a right hip spinning motion. Rory McIlroy usually doesn't have a "blocking" problem when he is swinging rhythmically and ultra-smoothly, but occasionally he has too much right hip spinning motion that produces "blocking" and resultant wayward drives.

Many professional golfers occasionally complain of being "blocked" during their mid-downswing, and Tiger Woods has frequently stated that it is has been a lifelong problem that he has had to deal with throughout his professional career.

Here is a link to a you-tube video (dating from the early 2000s) where Tiger Woods (together with his coach Butch Harmon) discuss this "blocking" problem

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xOecUNBV_Q0

Between the 2.00-2:33 minute time point of the video, Tiger Woods describes his "ole swing" where he got "stuck" because his right hip was blocking his right elbow at the P5.5 position.

Here is a capture image from the video.

In that capture image, note that Tiger Woods is demonstrating being "stuck",

which is causally due to an over-assertive right hip spinning motion that

"blocks" his right elbow.

In the video, Tiger Woods describes a Butch Harmon-inspired drill where he had to endlessly practice "getting his arms/club more in front of him". I believe that Butch Harmon's advice/drill represented a band-aid approach that didn't really work well over the long term because Tiger Woods continued to suffer from the same "blocking" problem in his later career. I think that it would have been better if Tiger Woods dealt with the "true" causal issue - a right hip spinning problem - and the optimum solution may have been a change in the pattern of his rotary pelvic motion to a pro golfer's type of rotary pelvic motion (as prototypically manifested by Adam Scott).

Although right hip spinning may occasionally cause a "blocking" problem in skilled professional golfers, it can become a much greater problem in unskilled amateur golfers who start their downswing's pelvic motion by "kicking-in" their right knee while simultaneously activating their right gluteus maximus muscle. That biomechanical combination can produce an exaggerated degree of right hip spinning that causes them to spin around their left leg while falling backwards onto their right foot. An exaggerated degree of right hip spinning can also predispose to roundhousing of the upper body if the unskilled golfer rotates his upper torso in unison with his pelvis, and that biomechanical combination can cause an OTT move and out-to-in clubhead swingpath through impact.

Now, let's consider the topic of pelvic shift, and consider whether any left-lateral pelvic shift towards the target must precede a counterclockwise rotary motion of the pelvis during the early downswing.

Many golf instructors believe that a golfer must start the downswing with a left-lateral shift of the pelvis towards the target before they start to rotate their pelvis counterclockwise, but I believe that their recommended "shift-then-rotate" pelvic motional swing pattern can produce a suboptimal pelvic motion during the downswing.

Consider some examples of that type of golf instructional teaching.

Example number 1 - Mark Panigoni swing video lesson - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4eVd0xjIR1I

Here is a capture image from the 1:50 minute time point of the video where Mark Panigoni demonstrates how one should slide the pelvis targetwards before one rotates the pelvis.

The above image shows Mark Panigoni at the P5.5 position.

I have drawn a red arrowed line vertically down from the outer border of his left

pelvis and it strikes the ground outside the outer boundary of

his left foot.

I believe that the outer border of the left pelvis should never get outside the left foot at any time during the downswing time period, and I believe that it will likely predispose to pushed shots (if the hands get too far ahead of the clubhead by impact - especially if it is associated with an incomplete release of PA#3).

Consider another example.

Example number 2 - Andrew Rice video lesson - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ixPSMG1m9Sc

In that drill, Andrew Rice positions the outer border of his left foot/pelvis about 4" from the wall, and he then states that one should drive the left side of the pelvis into the wall.

Here are capture images from that video showing Andrew Rice demonstrating that drill (without a golf club).

Image 1 shows Andrew Rice at address. Note that the outer border of his

left pelvis is about 4-6" away from the wall.

Image 2 shows Andrew Rice at the P5.5 position - with the left side of his pelvis pressed against the wall.

I think that this is a terrible golf instructional drill that will teach a student golfer a sub-optimal type of "shift-then-rotate" type of pelvic motion pattern.

Consider another example.

Example number 3 - Sean Foley video lesson - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JHuyVf7ulKE

Here are capture images from that Sean Foley video.

Sean Foley has positioned two red poles just outside the outer border of both

his left foot and his right foot. Note that he has folded his two arms across

the front of his chest because he only wants to demonstrate his desired pivot

motion.

Image 1 shows Sean Foley at address. Note that his pelvis is roughly centered between his feet.

Image 2 shows Sean Foley at his end-backswing position. Note that the distance between the outer border of his right pelvis and the red pole (alongside his right foot) has increased because Sean Foley has "turned inside" his right hip during his backswing's rotary pelvic action. I agree with Sean Foley that one shouldn't "turn-over" the right hip using a swaying motion of the right thigh combined with a rightwards-leaning motion of the upper body (which he demonstrates in his video) and I agree with Sean Foley that his "turning inside" his right hip is the optimal pelvic motional technique - where the pelvis remains roughly centered between the feet and where there is no weight shift (COM-shift) during the backswing action.