Downswing

Click on any of the hyperlinks to rapidly navigate to another section of the review: Homepage (index); overview; grip; address setup; backswing; impact; followthrough-to-finish

Introduction

I have noted that this downswing chapter is my golf website's most popular chapter, and I recently decided to completely rewrite this chapter (in February 2009) so that it reflects my latest (much more advanced) thinking regarding the optimum method of executing a downswing action. When I *originally wrote this downswing chapter in December 2006, I mainly focused my attention on describing the initiating lower body move that starts the downswing, but I now believe that there is much better way of thinking about, and describing, the entire downswing process.

(* I have decided to keep my original downswing chapter on my website, so that interested website visitors can read my original version if they are interested in understanding the evolution of my thinking regarding the golf swing).

When a golfer thinks of the primary purpose of the entire downswing process, he should break it down into its necessary components. The first purpose of the downswing process is the need to generate swing power. The major source of swing power in the modern golf swing is the pivot action, and a modern day golfer primarily uses his pivot-drive to power the swing. However, swing power is not transmitted directly to the swinging club. Rather, swing power is transferred from the pivoting torso to the swinging arms, which then apply that power to the clubshaft. I will describe the process of how that power is generated and transmitted to the swinging club in the downswing in the next section of this downswing chapter.

The second purpose of the downswing process is to ensure that the clubshaft moves in space in the "correct" manner so that it will allow the golfer to produce an in-to-in clubhead swingpath through the impact zone. If a golfer learns how to keep the clubshaft "on plane" during the downswing, while shallowing the clubshaft plane, then it will allow the clubhead to approach the ball along a shallow inside track, and eventually move in-to-square-to-in through impact. The third purpose of the downswing process is to ensure that the clubface is square at impact, so that the ball flight will be straight. If the clubhead swingpath is in-to-in through impact, and the clubface is square at impact, then the ball should fly straight towards the target. I will describe the optimum method of achieving these goals in a following section of this downswing chapter.

In my description of the mechanics/biomechanics of the downswing, I will primarily be describing a left arm swinger's action (which represents the traditional/conventional swing action). It is also possible to perform a downswing using a hitter's action or a right arm swinger's action, and they operate according to a different set of golf swing fundamentals. I have described the fundamental differences between left arm swinging, right arm swinging, and hitting in another review paper called "Left Arm Swinging, Right Arm Swinging and Hitting".

How to generate swing power in the downswing

Most professional golfers, who are left-arm swingers, generate swing power using a pivot-driven swing technique. During a pivot-driven swing, a golfer pivots in space and the energy derived from the pivoting torso causes the left arm to be propelled towards the ball. The left arm is essentially inert in the golf swing, and it doesn't produce energy by itself. The left arm is basically is swung across the front of the rotating torso and it swings the club towards the ball after the club is released. How does the pivot action transfer energy to the swinging golf club?

A popular method of understanding, and describing, how the pivot action powers the golf swing is the kinetic link theory (or conservation of momentum theory).

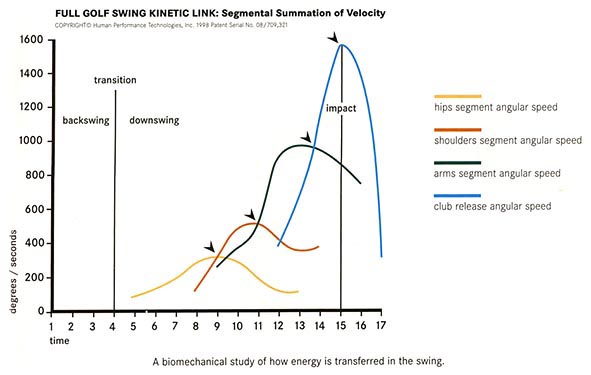

Here is a diagram depicting the kinetic link theory.

Diagram depicting the kinetic link theory - from reference number [2]

The kinetic link theory is based on the belief that energy is transferred from one body part to the next body part in a set kinetic chain sequence and that energy is conserved during this energy transferral process (according to the law of conservation of momentum). This conserved energy is finally transmitted to the golf club, which is the final link in this kinetic chain sequence. According to this theory, energy is produced when the golfer pivots his lower torso against the resistance of the ground. That energy causes the pelvis (lower torso) to rotate in space. Then, according to the law of conservation of momentum, that energy is transmitted from the lower torso to the upper torso when the lower torso decelerates. According to this theory, the transmitted energy will cause the upper torso to rotate roughly twice as fast as the lower torso. Then, the upper torso will transfer that energy to the arms when the upper torso decelerates and the transmitted energy will cause the arms to rotate twice as fast as the upper torso. Finally, the kinetic link theorists believe that the energy (which was conserved throughout this transmission process) will be transferrred to the club in the late downswing.I personally have very little sympathy for this oversimplistic kinetic link theory. I think that it is far too simplistic from a conceptual perspective, and I believe that there is little scientific evidence to support this theory. I can readily accept the idea that energy is produced when the lower torso rotates at the start of the downswing, and I can readily accept the fact that a certain amount of this energy is passively transmitted to the upper torso (via the spine and external torso musculature). However, I believe that most of the energy required to rotate the upper torso is derived from the active muscle contraction of mid-upper torso muscles, and that only a certain amount of the energy required to rotate the upper torso is passively derived from the rotating lower torso. I also don't believe that energy is transmitted from the rotating torso to the swinging arms across the shoulder joint space according to the principle of conservation of momentum - like energy is transmitted down the length of a whip when a lion tamer cracks his whip in a circus ring. I actually don't believe that any energy is transferred from the rotating torso to the left arm across the left shoulder joint (as occurs in the uniform structural material of a cracking whip). I believe that the left arm is essentially equivalent to an inert lever and I believe that the left arm is totally passive in a golf swing. It simply acts as a passive lever that is moved in space in a pivot-driven golf swing due to movement of the rotating upper torso. During the backswing the left arm is loaded across the upper chest wall, and a golfer can sense the loading pressure at pressure point #4 (the left pectoral area where the upper left arm presses against the chest wall) at the end of the backswing. During the early-mid downswing, the upper torso rotates at a fast speed, and a golfer will experience increased loading pressure at PP#4 when the upper torso rotates against the inertia of an inert left arm. The inert left arm will travel at the same speed as the rotating upper upper torso in the early/mid downswing because it is simply being passively pushed down-and-out-and-forward towards the ball by the rotating upper torso. The following diagram depicts the kinetic sequence in a pivot-driven swing.

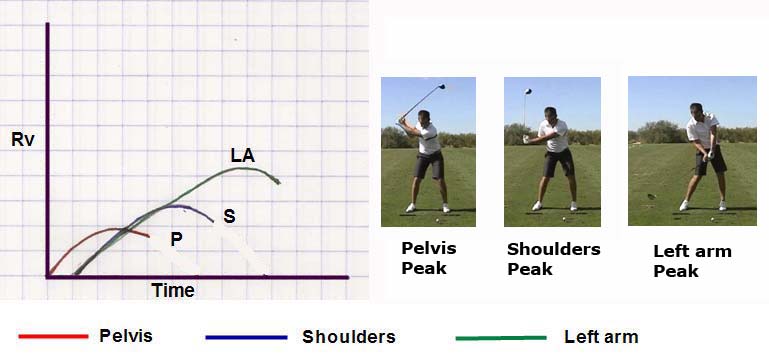

Kinetic sequence during the downswing action in a pivot-driven golf swing

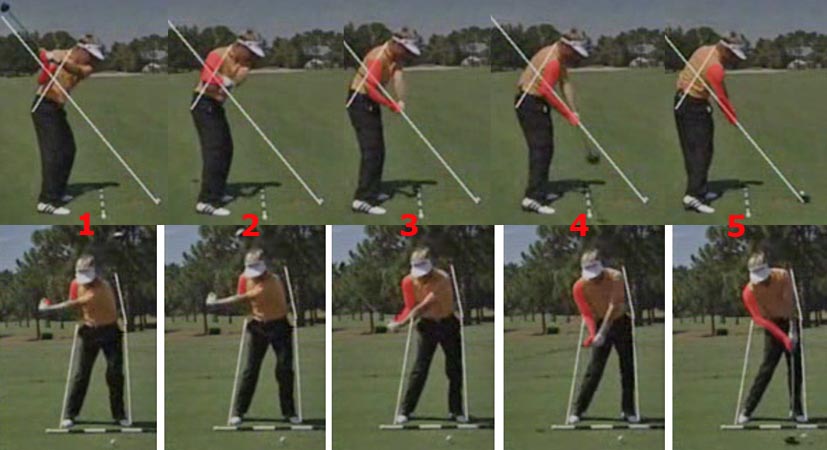

Rv = Rotational velocity = Angular speed.In a pivot-driven golf swing, the pivot action's kinetic sequence should start from the ground-up - the pelvis should rotate before the upper torso. According to this diagram, the pelvis starts rotating at the start of the downswing, but in many professional golfers the pelvis will actually start rotating in the late backswing (while the club is still moving to its final end-backswing position). The pelvis (lower torso) starts rotating before the shoulders (upper torso) and a certain amount of the energy needed to rotate the pelvis is passively transmitted to the upper torso via the spine and external torso musculature. However, the shoulders actually start actively rotating almost immediately after the pelvis starts rotating, and the shoulders don't have to delay their maximum speed of rotation until the pelvis decelerates (as predicted by the kinetic link theory). The pelvis starts to decelerate at the end of the early downswing (when the hips become square to the ball-target line) due to the fact that the golfer has transferred his weight onto a straightening left leg, that becomes increasingly weighted/braced. The straightening/weighted/braced left leg acts as a firm supportive post that resists any left-lateral forward movement of the pelvis - especially if the head is kept stationary (because the stationary head stabilises the upper spine). The shoulders (upper torso) start actively rotating very soon after the pelvis starts rotating at the start of the downswing, and the shoulders reach their maximum speed of rotation very soon after the pelvis reaches its maximum speed of rotation - occurring in the earliest part of the mid-downswing, when the shoulders are nearly square to the ball-target line (see small inserted image of Aaron Baddeley in the above diagram). The upper torso naturally/automatically decelerates when the mid-upper torso muscles (that actively rotate the upper torso) shorten. At the end of the backswing, these mid-upper torso muscles are optimally stretched, and they contract very forcefully in the early downswing thereby causing the upper torso to rotate very fast in the early downswing. When these actively contracting mid-upper torso muscles shorten, they can no longer produce much energy and the upper torso rotation naturally/automatically decelerates during the mid-downswing. When the upper torso decelerates, the left arm can freewheeel away from the chest wall towards impact at a faster speed because there is no impedance to the freewheeling movement of the left arm away from the chest wall. One can think of the left arm being passively catapulted away from the chest wall, and the distance between the hands and the right shoulder should progressively increase during the mid-late downswing - as can be seen in this photo-sequence of Ben Hogan's downswing.

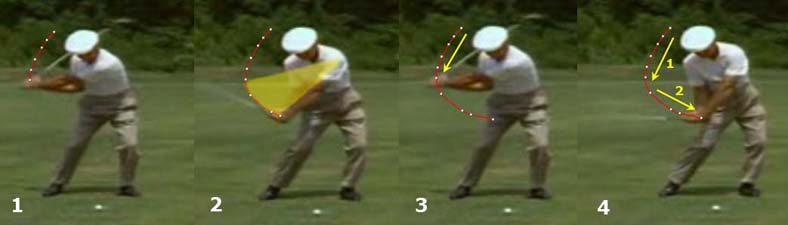

Ben Hogan's downswing - capture images from a swing video

Ben Hogan starts the downswing pivot action with a pelvis shift rotation movement (lower body movement) - images 1 and 2. Note that the left arm separates from the chest wall and freewheels towards impact after the pivot action subsides - images 3-5.A beginner golfer needs to understand two very important points about a pivot-driven golf swing - i) The kinetic sequence should evolve in a set manner (pelvis => shoulders => arms); and ii) The left arm should swing freely, and with progressively increasing speed, towards impact. A golfer must avoid getting the kinetic sequence out-of-order by starting the downswing with a shoulder (upper body) and/or arm movement. If the kinetic sequence is not optimised, then two major problems occur. The first problem is that an out-of-order kinetic sequence (where the arms move before the torso) decreases the amount of swing power - because the power of the pivot-drive action is not available to move the inert left arm if the left arm is pulled away from the chest wall before the torso starts to rotate in space. The second problem that often occurs when the kinetic sequence is out-of-order is that the clubhead path becomes out-to-in rather than in-to-square-to-in.

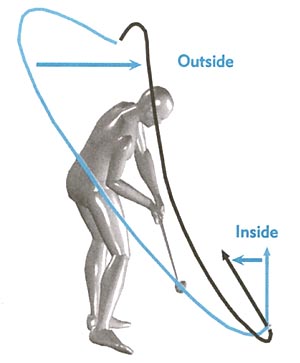

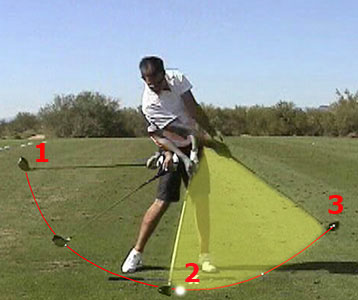

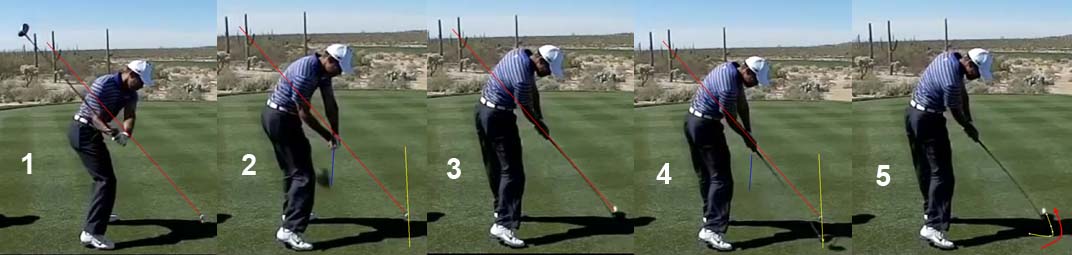

Consider this diagram from the "Swing Like a Pro" book [3].

Downswing clubhead swingpath - from reference number [3]

The optimum clubhead path is depicted in blue, and the non-optimum clubhead path is depicted in black. A high handicapper, beginner golfer often starts the downswing by simultaneously performing two moves that are out-of-sequence from a kinetic sequence perspective - i) actively pulling the club down towards the ball with his hands while ii) actively turning the right shoulder down towards the ball in a too-horizontal roundhousing manner. Those two moves throw the clubshaft outwards away from the body in the direction of the ball-target line, and the clubhead soon crosses the toe-line (start of the black line path). From that point on, the clubhead passes along a steep path down to the ball and reaches the ball from a slightly out-to-in direction (black arrowed path), which causes a pull (if the clubface is square to the clubhead path at impact), a pull-hook (if the clubface is closed to the clubhead path at impact) or a pull-slice (if the clubface is open to the clubhead path at impact). Beginner golfers who execute this over-the-top move sometimes seem to be spinning their shoulders in a circle around a passive lower body (pelvis) and inactive legs. As a beginner golfer gains more experience, and more control, he learns to minimise the spinning motion and he steepens his shoulder turn at the start of the downswing - and this produces a downswing motion, which the SLAP authors call an "upper body dive" action [3]. The upper body dive action can be perceived to be an upper body move that gives an outside observer an impression that the beginner golfer is lunging at the ball with his upper body, as demonstrated in this next photo from the "Swing Like a Pro" book [3].

Upper body dive - from reference [3]

You can sense that the beginner golfer (model) is throwing his upper body towards the ball in the above photo. Note that the right shoulder has moved outwards towards the ball-target line, and note that it is starting to cross over the toe-line in the early downswing. Note that the hands have been thrown away from the body and they are well forward of the toe-line. To complete the downswing, the beginner golfer (model) has to execute an out-to-in swingpath by pulling his hands across the body (in the direction of the blue arrowed line). He then subsequently has to complete the followthrough/finish phase of his swing by moving his hands inside and around-the-body along a low followthrough hand swingpath.Consider the "real-life" series of images of an anonymous golfer performing an "upper body dive" downswing movement.

Anonymous golfer performing an "upper body dive" downswing movement

Note how the anonymous golfer starts the downswing with an upper body movement (right shoulder rotation) that throws the hands and clubhead over the toe line along a steep downswing path (image 1). Note how the steep "over-the-top" movement of the hands then produces an out-to-in clubhead swingpath as the anonymous golfer pulls his hands inwards towards his body during the remainder of the downswing and early followthrough (images 2, 3 & 4).To correct this problem, the beginner golfer needs to re-think his entire approach to the downswing, so that he can achieve a PGA tour player-style downswing clubhead swingpath.

Downswing clubhead swingpath - from reference number [3]

Consider the downswing clubhead swingpath of an idealised professional golfer model - The ModelPro (in blue).Note that the clubhead first moves backwards (away from the ball-target line and towards the tush line) before it descends in a shallower arc towards the ball along an inside track. How does the professional golfer execute this backwards move (away from the body, away from the ball-target line) of the clubhead in the early downswing. You may imagine that the ModelPro golfer deliberately, and actively, first pulls the clubshaft backwards with his hands and then secondly loops it down to the ball. However, the hands are essentially passive in the modern, pivot-driven downswing, and the clubhead first moves backwards (away from the body, away from the ball-target line) because the first downswing move is a lower body move. That is a key element in the modern, pivot-driven downswing - the lower body moves first, and the upper body moves secondarily.

Starting the downswing pivot action - the magic move

Ben Hogan, the famous golfer, can be considered to be the originator of our fundamental ideas regarding the modern golf swing, and he described his ideas about this critical downswing move in his famous book "Five Lessons" [4] first published in 1957.Ben Hogan stated that one should think of starting the golf downswing from the ground up. In other words, the downswing should start with the lower body moving first, and the upper body moving second.

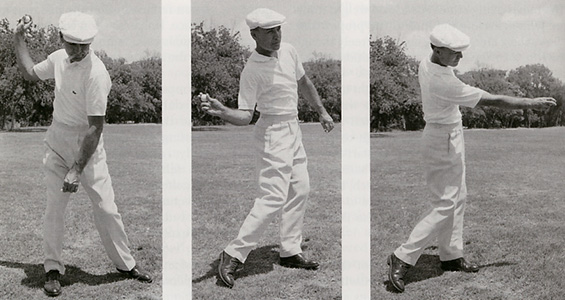

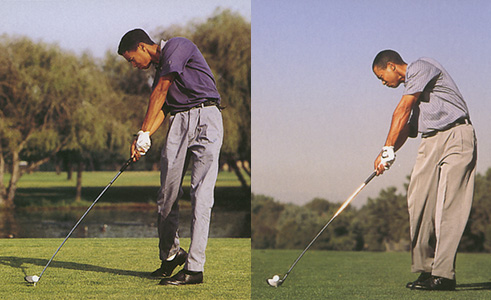

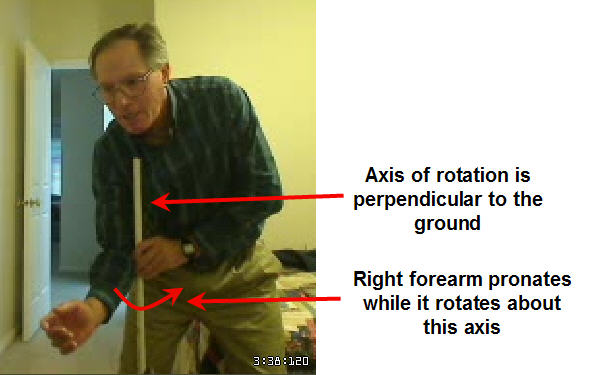

Ben Hogan stated that the motion of the modern golf downswing is very similar to the motion of a baseball infield player throwing a side-throw (half side-arm, half underhand) ball to the first baseman.

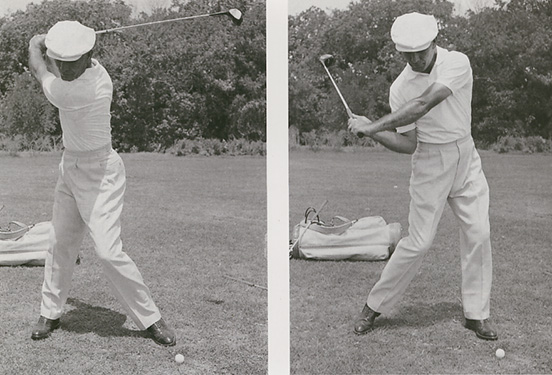

These are famous photographs of Ben Hogan demonstrating this side-throw ball throwing motion in posed (simulated slow motion) photographs.

Ben Hogan performing a side-throw ball throwing movement - from reference number [2]

Hogan stated that a ball thrower first inaugurates the side-throw ball throwing action with a lower body (pelvis) shift-rotation movement towards the target. Then, secondly and near simultaneously, a ball thrower brings the right elbow down to the right hip area (to a pitch elbow position) so that the right elbow leads the right hand. The sequence of movements can be thought of as occurring in the following sequential manner-: pelvis shifts to the left and transfers the lower body weight onto the lead foot => right shoulder moves forward while the right elbow simultaneously moves down to the right hip area with the right hand held back behind the right elbow (after the right hip has "cleared" thus making space for the right elbow) => right elbow actively straightens, right wrist unhinges, and the ball is released.Ben Hogan also stated that one should conjure a mental image of a boy skipping flat stones across a still pond. The boy would deliberately shallow the plane of his side-throw throwing action so that the stone would travel nearly parallel to the ground - in order to increase the likely number of skips-across-the-pond.

Ben Hogan stated that one should think of the golf downswing in a similar manner - as a side-throwing (stone skipping) action across the body, whereby the clubshaft angle is automatically/passively flattened during the early downswing.

Ben Hogan simulating the initial downswing motion - from reference number [2]

Note five important features of Ben Hogan's simulated initial downswing action-: i) The pelvis shift-rotates to the left (hip squaring action) and this lower body move initiates the downswing action; ii) the right elbow is pulled down to the right hip area (into a pitch elbow position) - partly as a result of this pelvic shift rotation movement, and partly due to an active adduction movement of the right upper arm - and the right elbow leads the hands; iii) the right shoulder is pulled downplane in the direction of the ball and the right arm is brought close to the torso; iv) the 90 degree angle between the left forearm and clubshaft remains unchanged in the initial downswing; v) the right forearm remains at a ~90 degree angle relative to the clubshaft; vi) and the clubshaft plane is automatically shallowed (flattened) causing the clubshaft to bisect the right upper arm in the second photo.It is important that a golfer understand that Hogan implied in his book that the arms/clubshaft are passively pulled down to waist level as a result of the lower body movement, and that a golfer shouldn't have to actively pull the arms/clubshaft down to waist level as a totally separate/independent action. Ben Hogan stated that his arms/hands "get a free-ride" down to waist level when he shift-rotates his pelvis at the start of the downswing [4]. Note that the intact power package arm assembly (left arm loaded across the chest wall and bent right elbow with the right forearm at right angles to the clubshaft) seemingly gets passively pulled down to waist level. Ben Hogan implied that he is not actively pulling his right arm towards the right side of his torso and that he is not actively pulling his right elbow down to his right hip area as a separate/independent action. However, all of these three events are happening simultaneously. I therefore personally think that it is better to think of these three motions, which are happening simultaneously, as being active motions - i) a shift rotation movement of the pelvis; ii) a downplane motion of the right shoulder and iii) an adduction motion of the right upper arm towards the right side so that the right elbow gets driven towards its pitch position alongside the right hip (with the right elbow leading the hands). I particularly believe that it is important for a golfer to ensure that the right arm moves actively towards the right side of the torso, so that the right elbow remains bent and the right forearm flying wedge maintains its constant relationship with respect to the left arm flying wedge - thereby keeping the power package's internal alignment intact. In other words, I believe very strongly that the right upper arm's adduction movement must be conceived to be an active motion, and not a passive phenomenon (as Ben Hogan implied when he stated that the "arms get a free ride").

Here is an animated gif image (created by Kelvin Miyahira), which demonstrates how the right elbow is actively brought down to its pitch position - via an active adduction movement, and internal rotation movement, of the right upper arm (while the right elbow bend is maintained).

Alvaros Quiros

Note how the active adduction movement of the right upper arm causes the clubshaft to shallow-out during the early downswing - while the pelvis is shift-rotating. It is incorrect to think that the active pelvis shift-rotation movement independently causes the clubshaft shallowing action. If a golfer incorporates this active right arm adduction movement, that actively pulls the right elbow down to its pitch location in front of the right hip area, then he is less likely to get "stuck" - which is a problem that has plagued Tiger Woods throughout his golfing career.

Here is a capture image from a swing video ( http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PplQjd6ZP88 ) showing Tiger Woods describing/demonstrating his "stuck" position - where his pelvis has out-raced the arms (power package slotting phenomenon), and where his right elbow is trapped behind his right hip.

Tiger Woods demonstrating his "stuck" position - capture image from his swing video

This "stuck" problem is less likely to occur if a golfer actively adducts the right upper arm at the same time, and at the same speed, as he performs the pelvic shift-rotation movement that initiates the downswing action. There must be perfect synchrony between the rotating torso action and the power package slotting action, so that the arms are essentially rotating at the same speed (rpm) as the rotating torso. A golfer must "feel" that he is keeping the arms in front of his rotating torso at all times in the downswing, and he must avoid allowing the torso to out-race the arms (from a rotational perspective).Consider the downswing pelvic action in greater detail.

If you look at Ben Hogan's leg movements, you will notice that the left knee is bent and the left heel is seemingly unweighted at the end of the backswing. Then, during the initial pelvis shift-rotation movement, the left knee moves away from the right knee as the lower body's weight is transferred onto the left foot (replanting of weight onto the left heel). The left forefoot is still significantly weighted at the end of the backswing, and when the left leg gets increasingly re-weighted in the early-mid downswing, most of the re-weighting "feeling" should be "felt" in the left heel (as the left pelvis is pulled back towards the tush line).

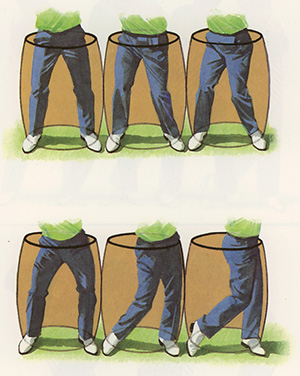

If you look at Ben Hogan's pelvis, you can sense that the pelvic movement is primarily a rotation of his left buttock backwards (away from the ball-target line and towards the tush line) while he is simultaneously transferring his lower body's weight onto his left foot - as if he were turning his left back trouser pants pocket back away from the ball-target line in a left hip clearing action.

Ben Hogan has an interesting diagram in his book [4] highlighting this initiating pelvic movement.

Idea of an elastic strip - from reference number [4]

Ben Hogan stated that one should "imagine, that at address, one end of an elastic strip is fastened to a wall directly behind one's left hip and that the other end is fastened to the front of the left hip bone." Then, during the backswing, when the pelvis rotates 45 degrees to the right, the elastic strip becomes stretched. The downswing starts when the elastic strip snaps back, rapidly rotating the left hip around to the left (hip squaring action). It is important to realise that a very small lateral shift of the pelvis to the left must accompany the rotation of the the left hip around to the left because the elastic band is attached to the front of the left hip.

Addendum added June 2007: I have written a detailed review paper called the "The Backswing and Downswing Hip Pivot Movements: Their Critical Role in the Golf Swing". This review paper provides much more explanatory detail regarding this important downswing lower body movement, and it is available in the miscellaneous topic section of this website. I have also described this pelvic motion in much greater depth in another new 2009 review paper called "Book Review: The Slot Swing - Jim McLean".

If a beginner golfer starts the downswing with a pure rotatory right pelvic movement, rather than a left-lateral pelvic shift-rotation movement, then that pure rotatory right pelvic movement will cause the right hemi-pelvis to leave the tush line and immediately rotate forward of the toe line (hip spinning), and it will secondarily cause the right shoulder to immediately be thrown forward of the toe-line (an "over-the-top" upper torso spinning movement that must definitely be avoided). The right shoulder must initially be held back behind the toe line, and not prematurely cross the toe line in the early downswing. By starting the downswing with a shift-rotation movement of the pelvis (a hip squaring action due to a pulling back of the left hemi-pelvis towards the tush line while the pelvis is shifting left-laterally towards the target), a beginner golfer should experience a right shoulder "side-bending feeling" - a distinct "feeling" that the right shoulder is dropping downplane towards the ball. Note how the golfer's right shoulder has dropped downwards-and-ouwards towards the ball in the above pencil diagram, as the right elbow moves rapidly down to the right hip area at the start of the downswing. To achieve that "side-bending feeling" of the upper torso, a beginner golfer must have a distinct feeling that the rightwards tilted spine is tilting even further away from the target during the initiating pelvic shift-rotation movement (and this increased degree of rightwards spinal tilt is called secondary axis tilt). Secondary axis tilt occurs because the left-lateral pelvic shift movement towards the target at the start of the downswing causes the lower lumbar spine to also move leftwards. If the head is kept stationary (thereby stabilising the position of the upper spine), then the entire spine must acquire a greater degree of rightwards spinal tilt in the early downswing as a result of the left-lateral pelvic shift movement. That increased degree of rightwards spinal tilt causes the right shoulder to move downplane when the shoulders start to rotate perpendicularly around the spine in the mid downswing.

Here is a link to an excellent video of Ben Hogan demonstrating the initiating shift-rotation move of the hips - http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QL_6M_xZvq0

Note how Ben Hogan starts the downswing by pulling his left hemi-pelvis back away from the ball-target line (and towards the tush line) in a hip squaring action. Note how his entire power package assembly is pulled down to waist level as a direct result of his initiating lower body shift-rotation movement.

Now, consider the downswing-initiating movement of another PGA tour golfer - Aaron Baddeley.

Aaron Baddeley starting the downswing - from reference number [1]

This photo demonstrates the first active body movements that occur when Aaron Baddeley initiates the downswing. In particular, note-: i) that his left pelvis has rotated backwards (towards the tush line) thus squaring the hips; ii) that there is a definite lateral shift of the pelvis to the left (towards the target); iii) that his left knee has moved away from the right knee causing a widening of the distance between the knees; iv) that his lower body weight is replanted back onto the left foot. I believe that the left knee moves automatically, and without any need for conscious thought, as a result of the weight transfer to the left that occurs when a golfer shifts weight back onto the left foot and shift-rotates the hips. In other words, I think that a golfer only has to think of simultaneously replanting weight onto the left foot (primarily the left heel) and shift-rotating the hips, and that he doesn't have to consciously think about his knee action.A key thought for a beginner golfer is the thought that he must only bump the pelvis left-laterally to a small degree, so that his lower body weight is transferred onto the left foot - but never beyond the left foot. A golfer must never slide the pelvis too far left-laterally, so that the outer border of the left pelvis gets beyond the outer border of the left foot. If the pelvis slides too far left-laterally in the early downswing, that excessive sliding motion usually causes the spine and head to be pulled too far left-laterally, and that phenomenon predisposes to push-sliced shots (due to the fact that the hands get ahead of the ball by impact, which prevents the golfer from being able to square the clubface by impact). A golfer must acquire a distinct "feeling" that he is bracing his left leg/knee as he transfers weight onto the left foot, and that this "bracing of the left side" phenomenon creates a "feeling" of establishing a "firm supportive left side".

Note that a few right arm movements occur at the same time. Note that the right elbow is leading the right upper limb's movements (it can be seen below the left arm in image 2 above). Note that the clubshaft is still at right angles to the left forearm, which means that there is no active wrist/hand movements (no uncocking of the left wrist and/or unhinging of the right wrist). Note that the right forerarm is still at right angles to the right upper arm, and that there is no active extension of the right elbow, demonstrating that there is no active attempt to straighten the right arm (straighten the right elbow) during the early downswing.

Consider an image of Aaron Baddeley a moment later in the downswing.

Aaron Baddeley downswing - from reference number [1]

Note that Aaron Baddeley has continued his pelvic shift-rotation movement - the left hip has slid slightly more forward in the direction of the target, and the left pelvis is rotating backwards away from the ball-target line while he pivots over a straightening (increasingly braced) left leg. Note that the outer border of his left pelvis is still within the vertical boundary of his left inner foot. Note that the right upper arm has been pulled inwards against the right side of his torso and that the right elbow is adjacent to the right hip in a pitch elbow position. Note that the right elbow has not straightened, and note that the right forearm is still at right angles to the right upper arm. Also, note that the clubshaft is still at right angles to the left forearm and that the left wrist has maintained its cocked-up appearance and that the right wrist is still hinged back.Consider the initial downswing body movements in this behind-view of Nick Faldo (at roughly the same point in the downswing).

Early downswing - from reference number [5]

Note that the left pelvis has rotated back towards the tush line thus squaring the hips (image 2). Note that weight is being transferred to the left foot when he shifts his pelvis weight to the left and that it causes the left knee to automatically/naturally move away from the right knee. Note that the right elbow drops below the left arm on its way to the right hip area - due an active adduction of the right upper arm towards the right side of the upper torso.Note that the lower lumbar spine has moved towards the target (as a result of the pelvic shift-rotation movement) and that he has acquired a significant amount of secondary axis tilt as a result of the hip squaring action. The secondary axis tilt allows the right shoulder to move downplane when the shoulders start to rotate perpendicularly around the rightwards tilted spine.

It is critically important that a golfer move the right shoulder downplane, and not horizontally (roundhousing) or vertically (tilting), at the start of the downswing. A golfer must acquire a "feeling" that the right shoulder is moving downplane - towards the ball - and the right shoulder must move roughly parallel to the turned shoulder plane.

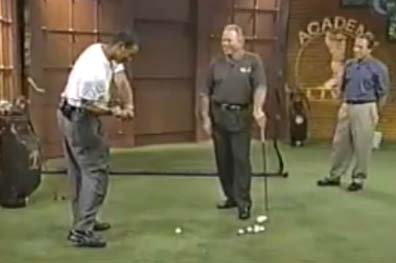

Here is a wonderful lesson by Robert Baker on his O factor concept, and he demonstrates how the initiating pelvis shift-rotation movement causes secondary axis tilt, and how that increased degree of rightwards spinal tilt allows the right shoulder to move downplane when the shoulders start to rotate around the rightwards tilted spine.

http://www.golf.com/golf/video/article/0,28224,1595277,00.html

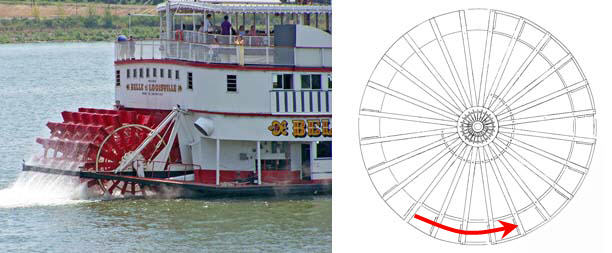

Robert Baker demonstrating the downplane movement of the right shoulder - capture images from his swing video

Robert Baker brilliantly demonstrates, using * two hula hoops, how the upper body is rotating along an angled axis (upper hula hoop axis) while the lower body is rotating along a more horizontal axis (lower hula hoop axis).(* Robert Baker has recently revised his swing video lesson, and he no longer uses the two hula hoops in his revised swing video presentation)

During the downswing, one should start the downswing move with a lower body shift-rotation move that eventually causes the left pelvis to slant upwards (when the left pelvis lifts up over a straightening left leg). This composite photo shows Robert Baker in the same mid-downswing position - from three different views. Note how the lower hula hoop axis is slanted slightly upwards and leftwards and that it causes the spine to be slanted in such a manner that the upper hula hoop axis (which is perpendicular to the rightwards tilted spine) becomes more vertically oriented at an angle to the ball-target line. The right shoulder should travel along the path of the upper hula-hoop loop in the mid-late downswing. If a beginner golfer understands this interlinked relationship between the two hula hoops, then it will allow him to understand how a "correct" lower body move (hip shift-rotation move) at the start of the downswing helps the right shoulder to move downwards and forwards along the "correct" downplane path and how it helps avoid an OTT move (roundhousing move of the right shoulder).

From a down-the-line view, one can more easily see how the right shoulder moves downplane, rather than horizontally (roundhousing).

Here is a DTL view of Sergio Garcia's driver swing.

Sergio Garcia - capture images from a swing video

Image 1 shows Sergio Garcia at the end-backswing position. The green line represents the shoulder turn angle in the backswing - note that Sergio Garcia turns his shoulders relatively horizontally in the backswing. The yellow line was drawn from the ball to the right shoulder (at its end-backswing position) and this line represents the right shoulder plane line (RSP line), also called the turned shoulder plane line (TSP line).In image 2, I have drawn another yellow line across Sergio Garcia's shoulders as he rotates his right shoulder under his chin in the late downswing/early followthrough. Note that this line is at the same inclined angle as the RSP/TSP plane line drawn in image 1, and this image demonstrates that Sergio Garcia has a steeper shoulder turn during the mid-late downswing (compared to the backswing), and that his right shoulder descends downplane at an angle that is roughly parallel to the RSP/TSP.

Rotating the right shoulder downplane is very important, because it helps direct the arms/hands along an inside track - similar to the hand path taken by a person who skips stones (using a side-throw/underhand throwing action). That allows the clubshaft approach angle to shallow-out and it allows the right forearm and clubshaft to approach the ball along a shallower inclined plane angle - usually along the *elbow plane (or close to the elbow plane).

(* I will discuss the clubshaft's plane-angle of attack in the next section on "keeping the clubshaft on-plane during the downswing").

If a golfer starts the downswing with a pelvic shift rotation movement, followed by an active right shoulder downplane movement, then the entire power package assembly will be passively pulled down to waist level along the appropriate down-and-out-and-forward path.

Consider that phenomenon in Ben Hogan's swing - see http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QL_6M_xZvq0

Ben Hogan's hand arc movement - capture images from his swing video

I used a spline tool to trace Hogan's hand movements during his downswing.Image 1 shows how his hands move down-and-out-and-minimally backwards in the early downswing as a result of the hip shift-rotation movement. The hands are not being actively pulled down in that direction. The hands simply move in that direction because the entire power package assembly is pulled down to waist level as a result of the lower body shift-rotation movement. Note that Hogan has already placed most of his lower body weight onto the left foot and this weight-transfer action braces the left leg creating a "firm supportive left side". The hips have nearly squared and the pelvis has already started to decelerate. The shoulders have also probably reached their maximum rotational speed, and are starting to decelerate at this time point.

Image 2 shows what happens in the mid-downswing when the shoulders decelerate. The left arm moves away from the chest wall and starts freewheeling towards impact (yellow-colored area) at a faster speed - note how the hands are moving further away from the right shoulder. It is at this time point in the downswing that the left arm is likely traveling at its fastest speed. A good golfer must allow this freewheeling left arm action to happen by allowing the pivot action to automatically/naturally subside in the mid-downswing, thereby catapulting the left arm towards impact.

Image 4 shows the directional change in his hand arc path that accompanies this left arm freewheeling action (arrow 2). It is important to note what effect this directional change in hand arc movement has on his clubshaft - note that the club has released and is starting to catch up to his hands. What causes the club to release at this time point? It is not due to any active uncocking action of the left wrist. It is entirely passive and entirely due to a centrifugal release phenomenon - and the club release phenomenon occurs automatically when the hands change direction and move in a circular arced motion. During the first part of the hand arc (arrow 1) the hands were moving in a relatively straight line direction - down towards the ground - and a straight line pull force along the longitudinal axis of the clubshaft doesn't induce the club release phenomenon. The club releases when the hand arc becomes more circular (arrow 2), and the speed of club release depends on i) hand speed during the time period when the hands are moving along a circular arc and ii) the radius of the hand arc's circular movement. The faster the hand speed at this time point and the "tighter" the hand arc turn radius - the faster the club release.

Here is a link demonstrating how a centrifugal release happens automatically/passively when the peripheral hinge joint (equivalent to the left wrist) of a double pendulum swing apparatus moves in a circular direction.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fBu30VbvBRY

If a golfer understands these two points, then he should have a clear understanding of how a golfer (swinger), like Ben Hogan, produces swing power in a full golf swing. It starts off with a pivot-driven swing action that starts from the bottom-up (lower body moves first, upper body moves secondarily). The pivot-driven swing action causes the left arm to be catapulted off the chest wall when the pivot-drive action automatically/naturally subsides in mid-downswing. The club automatically/passively releases shortly thereafter due to a centrifugal action. In other words, there is no need for right arm power in a swinger's action. Note that Hogan's right elbow is still bent at a right angle in image 4, which means that he is not supplying right arm push-power to the clubshaft by actively straightening the right elbow in a thrust action. Watch Ben Hogan's swing video over-and-over, and try to imagine how fast his left arm and clubshaft must be traveling between their position in image 4 (where the club is at the delivery position) and impact. They are traveling so fast that it is physically impossible to get them to travel faster by supplying a "right arm hit action" in the late downswing - by actively straightening the right elbow in the late downswing.

Many beginner golfers make the major mistake of trying to supply additional swing power when the hands/clubshaft reach the delivery position - clubshaft is parallel to the ball-target line = third parallel position - by actively using right arm push-power in a futile attempt to get the clubshaft to move faster in the late downswing. Any attempt to add right arm push-power to a swinger's action only disrupts the swing action, and interferes with the centrifugal release action. I spent a few hundred hours studying Homer Kelley's "The Golfing Machine" book [6] earlier this year, and I think that the most important lesson that I learnt from his book relates to the topic of power accumulator loading and release, and how a swinger uses different power accumulators than a hitter. This is a very complex subject, but all golfers will greatly benefit if they clearly understand the swing action differences between a swinger and a hitter. I have described the differences in great detail my review paper on "How to Power the Golf Swing", and I highly recommend that all my website visitors read that very important review paper. It may have a major effect on your approach to the golf swing. Most golfers are switters (golfers who unintentionally mix "swing" elements with "hitting" elements), and I believe that golfer should preferably choose to be either a swinger or a hitter, and not a switter.

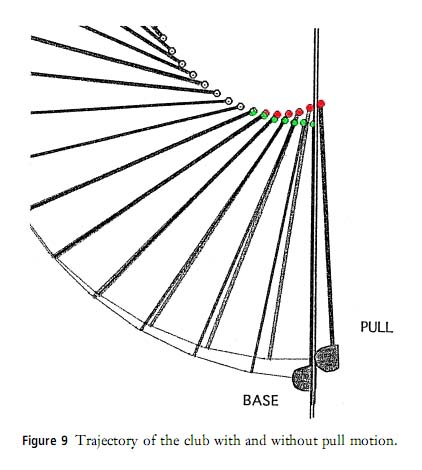

What I have described so far in this "swing power generation" section of this downswing chapter are the swing fundamentals of a swinger's action. A swinger powers the golf swing via a pivot-driven swing action that causes the left arm to be catapulted off the chest wall towards impact. The freewheeling left arm/hand pulls the clubshaft towards impact, and this pull-action is called drag-loading. The right arm does not supply any push-power in a swinger's swing action. If a golfer wants to apply right arm push-power in a drive-loading manner, then he must learn how to become a hitter. A hitter's action is very different to a swinger's action. A hitter doesn't use his pivot action in the previously-described "pivot-drive" manner in order to catapult the left arm off the chest wall towards impact. A hitter primarily uses a pivot action to move the right shoulder closer to the ball in the early downswing before he actuates power accumulator #1 (active right elbow straightening action). The right shoulder can be conceived to be the launching pad for the release of power accumulator #1 (the active right elbow straightening action), which causes the right forearm/right hand to push the clubshaft towards impact (drive-loading). The straightening right arm not only pushes the clubshaft towards impact, it also pushes the left arm/hand towards impact. In other words, a hitter doesn't use the pivot-drive to catapult the left arm towards impact - he uses the straightening right arm to push the clubshaft and the left arm towards impact. There is no centrifugal release of the club in a hitter's action because a hitter drives the clubshaft into impact (using an axe handle technique). I am not going to describe a hitter's action in any detail in this downswing chapter - interested readers can consult two of my detailed review papers - "How to Power the Golf Swing" and "Left Arm swinging, Right Arm Swinging, and Hitting" - for further details.

Keeping the clubshaft "on-plane" during the downswing

I have described how a golfer (swinger) should power the golf swing in the previous section. In this section, I am going to describe how a golfer needs to move the clubshaft "on-plane" during the downswing, so that he can generate an in-to-square-to-in clubhead swingpath that will allow a golfer to square the clubface at impact.

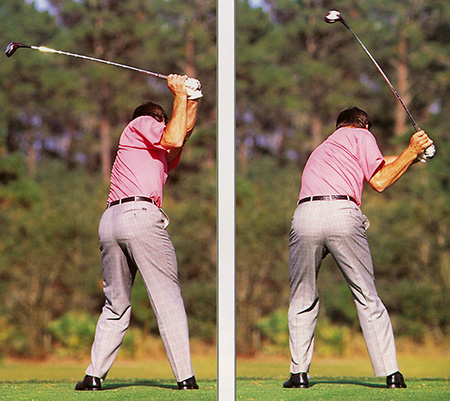

Consider the plane shifts that frequently occur in a golf swing. I am going to use Aaron Baddeley as an example because he is reflective of the double plane shift swing that most professional golfers use in their full golf swing.

Clubshaft planes - capture images from a swing video [1]

Note that Aaron Baddeley has his clubshaft on the hand plane (green line) at address - where an imaginary extension line drawn from the butt end of his clubshaft would point at his belt buckle.Note that Aaron Baddeley's hands/clubshaft moves to a higher plane during the backswing and that his hands/clubshaft end up just above the right shoulder plane (also called the turned shoulder plane = TSP) at the end of his backswing. The TSP is represented by a line drawn from the ball-target line to the right shoulder at its end-backswing position (blue line). Most professional golfers get their clubshaft to the TSP, or near the TSP (either just below the TSP line or just above the TSP line), by the end of their backswing.

Note that Aaron Baddeley's clubshaft descends to the elbow plane by impact (defined as a plane line drawn between the ball-target line and the right elbow at address). An imaginary extension line drawn from the elbow plane line exits the mid-back roughly halfway between the pelvic crest and the neck (red line). Most professional golfers get their hands down to the elbow plane, or very close to the elbow plane, by impact. Ben Hogan's clubshaft is slightly below the elbow plane at impact (and it is closer to the hand plane) while Brian Gay and Phil Mickelson have their clubshaft on a slightly steeper plane at impact (closer to the TSP than the elbow plane).

Aaron Baddeley has a double plane shift swing - the clubshaft shifts from the hand plane to the TSP in the backswing, and from the TSP to the elbow plane in the downswing. When the clubshaft descends from the TSP to the elbow plane in the downswing, it usually reaches the elbow plane by the time the club reaches the delivery position (third parallel position). A golfer can get the *clubshaft to move abruptly down from the TSP to the elbow plane at the start of the downswing (via a vertical drop of the hands) and then the golfer can pull the clubshaft down along the elbow plane to the delivery position - and that clubshaft-shallowing pattern is characteristic of Sergio Garcia's swing. Alternatively, a golfer can move the clubshaft slowly and gradually down from the TSP to the elbow plane during the early-mid downswing. Most professional golfers, like Aaron Baddeley, adopt that pattern.

(* I have described these alternative clubshaft-shallowing patterns in much greater detail in my new 2009 review paper "Book Review: The Slot Swing - Jim McLean")

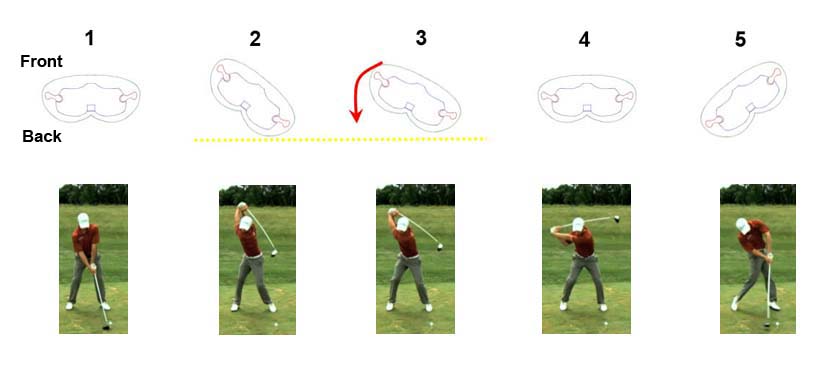

When the clubshaft shifts planes from the TSP to the elbow plane during the early-mid downswing, a golfer must ensure that the clubshaft remains "on-plane". The concept of keeping the clubshaft "on-plane" was described by Homer Kelley in his TGM book [5].

Homer Kelley stated in his TGM book [5] that a clubshaft is deemed to be "on-plane" if the end of the club nearest the ground always points at the base of the inclined plane (which is usually the ball-target line if the golfer's body stance is square to the ball-target line), and that the only time that this condition need not be met is when the clubshaft is parallel to the base of the inclined plane (ball-target line). The clubshaft usually becomes parallel to the ball-target line at four time points during an ideal on-plane swing - i) at the end of the takeaway (first parallel); ii) at the end-backswing position (second parallel); iii) at the delivery position (third parallel); and iv) during the early finish phase (fourth parallel). At all other time points, the end of the clubshaft (the end of the club that is nearest to the ground) must point at the ball-target line (or an imaginary extension of the ball-target line).

Here is an example of a perfect "on-plane" clubshaft motion during the downswing - Anthony Kim's swing [6]

Image 1 (end-backswing) and image 5 (delivery position) demonstrate that his clubshaft is parallel to the ball-target line. At all other time points, the end of the club nearest the ground (butt of the club in images 2, 3, 4 and clubhead end of the club in images 6, 7) points at the ball-target line (yellow dotted lines). Anthony Kim's swing is a perfect example of a swing where the clubshaft is always "on-plane" during the downswing - even while it is shifting planes from the turned shoulder plane (at the end-backswing) to the elbow plane (at impact). While it is shifting planes, it also fulfills Homer Kelley's definition of being "on-plane".If a golfer keeps the clubshaft "on-plane" throughout the downswing and followthrough, then he can be sure that he is generating a clubhead swingpath that is symmetrically in-to-square-to-in relative to the ball-target line, and I highly recommend that all golfers try to routinely achieve an on-plane downswing. There are different methods of practicing how to achieve an on-plane golf swing. One technique uses a dowel stick, and I demonstrate that technique in the swing videos that accompany my review paper on How to Move the Arms, Wrists and Hands in the Golf Swing. I also describe a second technique, using a flashlight (or clubshaft with in-built laserlights at either end of the clubshaft) placed in the right hand, in my review paper on How to Hit the Ball Straight. The flashlight/laserlight drill is very useful because it teaches a golfer that the right forearm/hand (via PP#3) is responsible for keeping the clubshaft on-plane. In other words, if PP#3 always traces the straight plane line (SPL), which is the base of the inclined plane (and usually the ball-target line), then a golfer knows that the clubshaft will always be on-plane. A golfer needs to realise that his "mind" must be in his hands (specifically PP#3 of the right hand), and he must realise that he can keep his clubshaft on-plane during the downswing by acquiring "educated hands" that allow him to consistently trace the SPL using PP#3.

Another good method of checking whether the clubshaft is on-plane is to look in a mirror while performing the downswing pivot action in slow motion while using a golf club (or dowel stick). The mirror should be positioned so that one can obtain a down-the-line view of one's arms/clubshaft in the mirror. Then, one can check to see if one is passing through certain checkpoints that indicate a perfect on-plane clubshaft movement - as the clubshaft smoothly/gradually shifts planes from the turned shoulder plane (at the start of the downswing) to the elbow plane (at the delivery position).

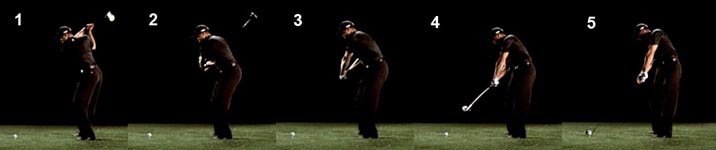

Consider Aaron Baddeley's downswing - as viewed from a down-the-line (DTL) view.

Aaron Baddeley - capture images from his swing video [1]

Yellow dotted line = Ball-target line (base of the inclined plane).

Checkpoint 1 (image 1) - when the left arm is parallel to the ground, the butt end of the clubshaft should point at the ball-target line indicating that the clubshaft is on-plane. The back of the flat left wrist should be parallel to the inclined plane (which is on, or preferably just below, the turned shoulder plane).Checkpoint 2 (image 2) - when the left hand has moved down slightly further it is now on a shallower plane (intermediate between the turned shoulder plane and the elbow plane). The back of the flat left wrist should be parallel to this shallower plane. The butt end of the clubshaft should point at the ball-target line (point X) indicating that the clubshaft is on-plane. The clubshaft should cut across the right mid-lower biceps.

Checkpoint 3 (image 3) - when the left hand has reached a position below waist level, the left hand should be on the elbow plane. The butt end of the clubshaft should point at the ball-target line (point Y) indicating that the clubshaft is on-plane. The clubshaft should appear in-line with the right forearm.

If the clubshaft passes through these checkpoints successfully, it indicates that the clubshaft has remained "on-plane" while smoothly and progressively shifting planes from the turned shoulder plane to the elbow plane.

If a golfer can successfully get his clubshaft to the elbow plane by the delivery position, then it easier to remain on-plane between the delivery position and impact - because a golfer merely needs to allow his clubshaft to descend down towards the ball along its pre-determined path.

Clubshaft path - from the delivery position to the end of the followthrough position

The above composite photograph of Aaron Baddeley demonstrates how the clubshaft moves from the delivery position (position 1) to impact (position 2) and further onwards to the end of the followthrough (position 3). This motion of the clubshaft through the impact zone should occur automatically/naturally, and a golfer doesn't need to use any active wrist/hand manipulation during this phase of the golf swing to keep the clubshaft on-plane through the impact zone. The clubshaft will automatically remain on-plane if a golfer allows the hand/clubshaft motions to occur without any interference. The reason why it will occur naturally/automatically is due to the fact that the club has already released (due to the centrifugal action - due to the release of PA#2) and it will continue along its circular arced track if the golfer simply allows it to happen without any interference - without making any attempt to "steer" the golf club in a straight line direction towards the ball. If the clubshaft was "on-plane" on the elbow plane at the third parallel (delivery) position, then it will continue to run along the surface of that inclined plane if the golfer allows it to happen in a biomechanically natural manner.The following video sequence shows a clubshaft traveling on an inclined plane board.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PIw1DERYvps

In that video demonstration, I am simply allowing the clubshaft to remain on the surface of the plane board while it descends towards impact (low point of the clubhead arc), and continues onwards through impact (beyond the low point of the clubead arc). A golfer must imagine his clubshaft remaining on his "selected" impact plane (eg. elbow plane) through the impact zone - from position 1 to position 3 in the above composite photo of Aaron Baddeley - without making any attempt to alter the movement of the clubshaft, and without making any attempt to deliberately close the clubface, during the clubshaft's passage through the impact zone The clubface will close naturally/automatically if a golfer allows it to happen in a biomechanically natural manner.

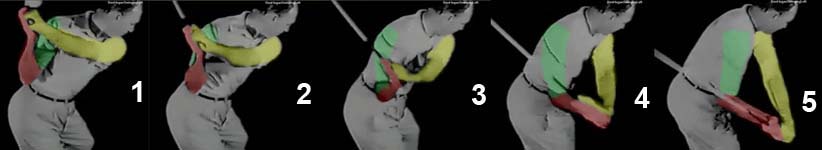

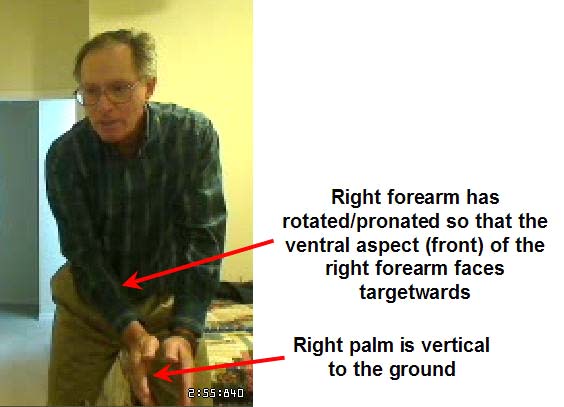

Note that the clubface and back of the flat left wrist/hand rotates about 90 degrees between the delivery position (position 1) and impact (position 2). This 90 degree left hand/clubface rotation is due to the release swivel action - a biomechanical phenomenon that happens automatically/naturally, and that doesn't require conscious/deliberate thought. Consider the biomechanical actions that occur during the release swivel action.

Aaron Baddeley's release swivel action - capture images from his swing video [1]

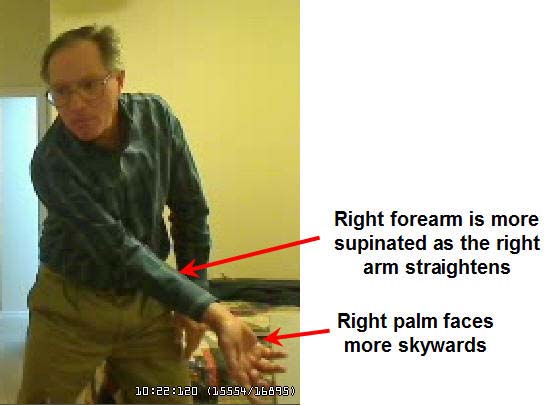

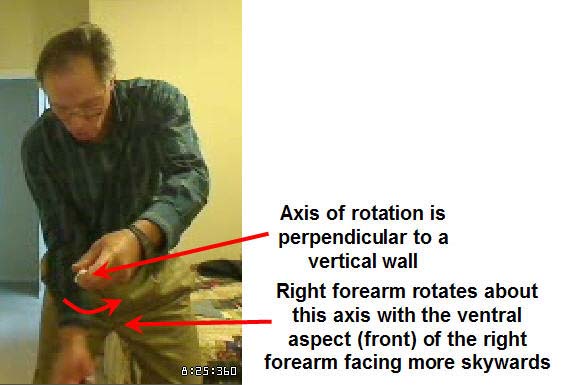

Image 1 shows Aaron Baddeley approaching the delivery position - note that the left arm-clubshaft angle is approximately 90 degrees. Note how the club releases as it passes the third parallel position and note how the clubshaft becomes progressively more straight-in-line with the left arm during the late downswing (images 2 and 3). This club release phenomenon (due to the release of PA#2) requires the left wrist to be relaxed so that it can passively uncock and become level by impact (nether upcocked or downcocked), and this uncocking action of the left wrist occurs passively/automatically due to a centrifugal force (due to the release of PA#2) and not due to any active left wrist uncocking action.Also, note how the back of the flat left wrist partly faces the ball-target line in the early swivel phase of the downswing (images 1 and 2) and note how the back of the flat left wrist (and right palm) faces the target by impact. This 90 degree rotation of the flat left wrist/hand occurs naturally/passively and it is partly due to external rotation of the left humerus at the level of the left shoulder socket and partly due to a left forearm supinatory movement. A golfer only needs to be relaxed so that these biomechanical actions can occur naturally/automatically/passively - the straight left arm naturally wants to adopt a *neutral position by low point (when the left hand is vertically below the left shoulder socket).

(* a neutral left arm is a left upper arm that is neither internally rotated or externally rotated, and a left forearm that is neither supinated or pronated).

A golfer should never attempt to actively roll the left hand into impact via an active hand-wrist rollover action.

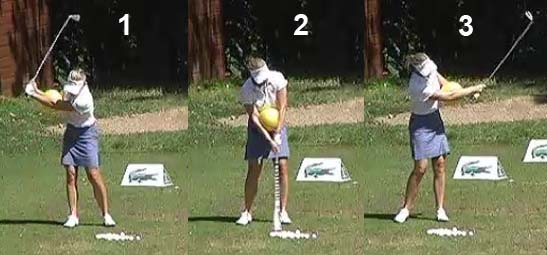

Some golf instructors incorrectly teach a swing methodology where they recommend that a golfer actively roll the hands over through the impact zone - and this active hand roll-over action is called a hand crossover release action.

Here is a link to AJ Bonar's article on his "magic move" - http://www.golf.com/golf/instruction/article/0,28136,1565175-1,00.html

AJ Bonar uses this composite photo in his article to demonstrate his magic move - which is an active hand crossover release action through the impact zone.

AJ Bonar's Magic Move - an active hand crossover release action through impact

In this composite photo, one can see that the right hand is pronating while the left hand is supinating post-impact (image 3) and one can see that this roll-over action is happening while the hands are below waist level.

AJ Bonar recommends that a golfer perform the hand roll-over action in the following manner-: "Now the fun part! About two or three feet before your hands reach impact, assertively rotate them toward the target. Imagine you're gripping a screwdriver and turning it counterclockwise. This closes the clubface, generating big-time power."

This "active hand roll-over action" golf tip recommendation is terrible advice, because the success of this "magic move" depends on perfect timing through the impact zone. Professional golfers don't use this "magic move" maneuver, because they cannot hope to time the move correctly. If a professional golfer cannot master this move, what's the likelihood of an amateur golfer mastering this "magic move"? Even AJ Bonar concedes that perfect timing is required, and in his article he concedes that imperfect timing can cause a hooked shot (if the clubface closes too much by impact). On page 4 of his article he answers a hypothetical question:

"Q. I'm hooking it. Now what should I do?

Don't panic. That means you're turning the face over, which is a good thing. But you're doing it too early. You want to feel that your right palm is facing the target at the moment of impact. Try holding off turning over your hands until they pass the ball. Also, experiment with opening the clubface even more at address. I like about 10 degrees, but more or less may work for you."Note how he addresses the issue of a hooking problem due to an imperfect performance of the "magic move". He states that the hooking problem is due to a too-early turn-over of the clubface (due to a too-early supination roll-over action of the left hand and/or too-early pronation roll-over action of the right hand) and he recommends that the golfer should delay the clubface roll-over action. However, that represents a huge "timing" problem and it is very unlikely that an amateur golfer can perfect the timing required to consistently execute a perfectly timed clubface roll-over action. His second solution is even more ridiculous! He suggests opening the clubface at address by 10 degrees to compensate for a too-early clubface roll-over action. Now, a beginner golfer is forced to juggle with two interacting factors - trying to determine the amount the clubface should be open at address to counteract the effect of a too-early clubface roll-over action.

All golfers must avoid this active hand roll-over action through the impact zone (between the third parallel and the fourth parallel postions), and they must clearly understand the biomechanics that cause the clubface to naturally roll-over during the clubhead's passage through the impact zone.

If a golfer has a problem squaring the clubface by impact, then he must first determine the "true" cause, and secondarily remedy that causal problem, rather than attempt to use any unreliable active hand manipulation technique in the impact zone. A golfer must think of his hands as being clamps on either side of the club's grip, and he must swing the club through the impact zone without attempting to actively manipulate the club in the vicinity of the ball. I have discussed this issue in great detail in my review paper "How to Move the Arms, Wrists and Hands in the Golf Swing" and also in the accompanying swing video lessons.

Further downswing insights - presented in a question-and-answer format.

I will progressively add more content to this section over a period of time.

Question number 1:

Does increasing pelvic rotational speed increase swing power?

Answer:

Not necessarily.

Watch the following swing video of Anthony Kim's swing and listen to the TV commentator's comments.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8finF6n64Qg

This TV commentator, like many TV golf commentators, is very unknowledgeable regarding golf biomechanics. He is making the irrational claim that Anthony Kim can generate a great deal of swing power because he has "fast hips" and that "fast hips" produces a large degree of torso-pelvic separation at impact (hips more open than the shoulders at impact) - and that this "increased degree of torso-pelvic separation at impact" phenomenon is causallly responsible for Anthony Kim's considerable swing power. This assertion is utter nonsense! In fact, if the hips (pelvis) outruns the upper torso and/or arms, then it is more likely that a golfer will have less swing power.

What happens if a golfer has a very assertive pelvic shift-rotation movement at the start of the downswing that causes his lower body to outrace the upper body? What will likely happen is that the arms will get left far behind and get stuck behind the right hip - and this phenomenon causes "blocking". This "blocking problem" has always plagued Tiger Woods' swing, and he is always fighting this problem. Consider a comparison of Tiger Woods swing from age 16 years versus age 24 years.

Tiger Woods swing - from reference number [7]

This comparison photograph of Tiger Woods' swing - aged 16 years (image 1) and aged 24 years (image 2) - was copied from his book [7]. Note that Tiger Woods' pelvis was nearly 90 degrees open to the target when he was 16 years of age, compared to about 45 degrees open when he was 24 years of age. Tiger Woods has always had very fast hips, and he has stated that "too fast hips" has been a life-long problem. He stated that when his pelvis rotates too fast in the downswing, that his arms get trapped behind his mid-upper torso and that he gets "blocked", which means that he has difficulty getting his arms around his right hip in the downswing. If he gets severely blocked, then he cannot square the clubface and he ends up pushing the ball to the right. He has also stated that he can sometimes "rescue the shot" and get the ball to fly straight by snap-flipping his hands through the impact zone in order to close the face down by impact. Tiger Woods has stated that he tries very hard to prevent his lower body moving too fast (relative to his upper body), and that he always tries to achieve better synchrony between the lower torso's rotational movement and the upper torso's rotational movement in the downswing.It is very important that a golfer realise that the kinetic sequence must evolve in a set sequence of accelerations/decelerations, and that if a golfer wants to hit the ball further by rotating his pelvis faster, then he must also be physically capable of performing the entire kinetic sequence faster. If a golfer cannot get the upper body, and arms, to also rotate appropriately faster when he starts the downswing with a very fast lower body shift-rotational movement, then his swing will become uncoordinated/asynchronised, and that will result in a loss of swing power and ball control.

Another important point is that the "true" cause of increased swing power in a pivot-driven swing (actuated by a faster pelvis shift-rotational movement) comes from an ability to swing the left arm faster (release power accumulator #4 faster). Power accumulator #4 is released by the upper torso, and not the lower torso, and one also needs to rotate the upper torso faster in order to generate a greater degree of swing power. An additional point that a golfer needs to understand is that the entire power package assemply release phenomenon must still remain synchronised and it must always occur in a set power accumulator release sequence (PA#4 release => PA#2 release => PA#3 release). A golfer will not get the clubhead to swing faster through impact if he releases power accumulator #4 faster, and if he gets the left arm to freewheel towards impact at a faster speed - if he is physically incapable of also speeding up the release of power accumulator #2, and then power accumulator #3, in a very synchronised manner, that allows him to square the clubface by impact, so that he can hit the ball squarely on the sweetspot. It is very easy to swing the hands down to impact very fast, but it is not easy to get the clubshaft/clubhead to keep up with the hands. If the hands get to impact well ahead of the clubshaft/clubhead, then the clubface will likely be too open at impact and this will predispose to push-sliced shots. Experienced golfers learn that their left arm/hand has to slow down momentarily just prior to impact (a phenomenon called "snapping the kinetic chain"), so that they can efficiently complete a release swivel action that will allow them to square the clubface by impact.

Question number 2:Ben Hogan stated in his book [4] that he wished that he had "three right hands". Does that mean that Hogan was a hitter, and that he used right arm/hand power to hit the ball with increased force?

Answer:

This question has been endlessly debated in many online golf discussion forums, and many forum participants have unequivocally stated that they "know" that Hogan was a hitter who used his right forearm/hand to supply increased swing power. The problem with their assertions is that their assertions are unsupported by any scientific/visual evidence and their assertions are also logically incoherent from a biomechanical perspective. They often claim that Hogan "hit with his right hand" when he entered the "hitting zone" - the impact zone between the 3rd parallel position and the impact position. However, I have never read a theoretical explanation that could rationally explain how Hogan could efficiently apply increased "hit power" with his right hand during the late downswing.

Between the 3rd parallel position (delivery position) and impact, the clubshaft is traveling extremely fast in a swinger who has sequentially released power accumulator #4, and then power accumulator #2, in an optimised manner. I cannot understand how a golfer can efficiently apply additional push-pressure against the grip end of the clubshaft (at pressure point #1 and/or pressure point #3) using his right arm/hand at this late time point in the downswing - if the golfer has an optimised release of power accumulator #4 and then power accumulator #2.

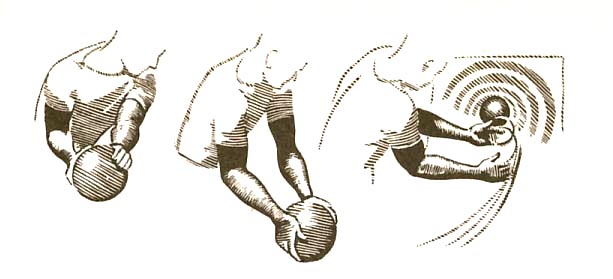

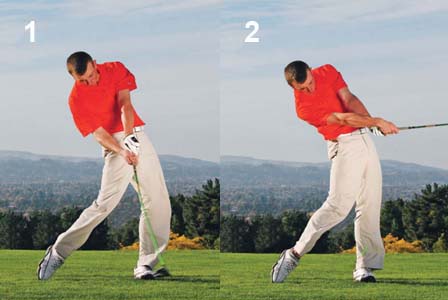

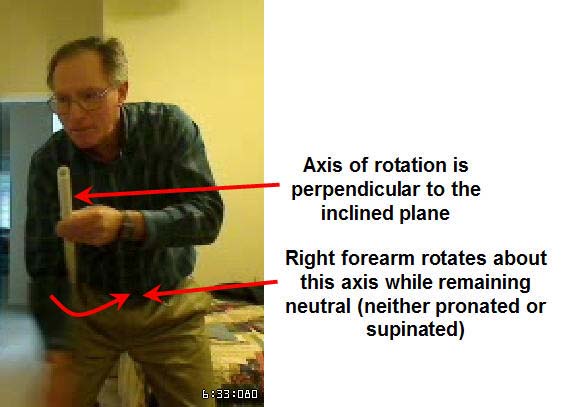

Ben Hogan addressed this question in his book [4] when he stated-: ""What is the correct integrated motion the two arms and hands make as they approach the ball and hit through it? What does it feel like as it is happening? Well, if there is any motion in sports which it resembles, it is the old two-handed baseketball pass, from the right side of the body."

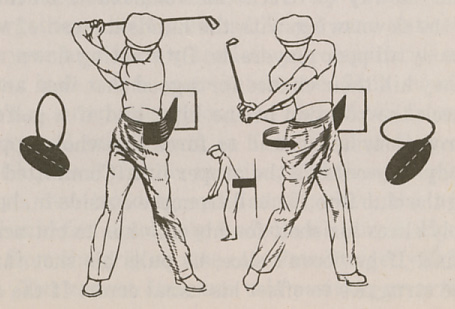

Hogan used the following diagram of a two-handed basketball pass in his book [4].

Two handed basketball pass - from reference number [4]

Hogan stated that one should imagine throwing the heavy ball towards the bulls eye of a target situated about 5 feet away. This throw motion is a two-handed motion involving the rotation of the torso and arms while the hands are situated on opposite sides of the ball. The motion does not involve any independent forearm rotary movements below the elbow in a twisting (corkscrew) motion as that would cause the ball to rotate around an imaginary horizontal axis passing through the center of the ball while the ball is being thrown towards the target. The throwing motion primarily involves an internal rotation of the right humerus in the right shoulder socket and an external rotation of the left humerus in the left shoulder socket, while the shoulder sockets are rotating around to the left as a result of the continuous rotation of the upper torso. That's the "feeling" a golfer should experience when swinging his arms across the front of his rotating body - the arms should swing in perfect synchrony with the rotating torso, and the hands should "feel" like passive clamps on either side side of the grip end of the clubshaft.If you think more deeply about this two-handed basketball pass, then you should realise that the two hands have to work in perfect unison, and the left hand should not pull the basketball faster than the right hand can push the basketball (and vica versa). The same analogy applies to a golf swing - the left hand is pulling the grip end of the golf club (secondary to the release of power accumulator #4 which causes the left arm to freewheel at a fast speed towards impact) and the right hand is pushing against the grip end of the club via pressure point number #1 (secondary to a right elbow straightening action). The right elbow has to actively straighten in the late downswing, so that the bent right wrist/hand can apply increased push-pressure against pressure point #1 (in order to constantly maintain extensor action throughout the downswing), but the right hand must not apply excessive push-pressure - because the right hand should not push the grip end of the club forward faster than the left hand is pulling the grip end of the club forward. A golfer should "feel" his right elbow actively straightening in the late downswing/followthrough phases of the swing, and the right triceps muscle must contract with enough active force to allow the right hand to keep up with the left hand. However, a golfer should never "feel" that the right hand is pushing the grip end of the club faster than the left hand is pulling the grip end of the club. The two hands have to work in perfect unison - as a perfectly synchronised unitary club-pulling structure. Hogan stated in his book [4] that the left hand must hit with the same amount of force as the right hand! If a golfer really had the equivalent of "three right hands", then the right hand would very likely overpower the left hand! I think that if a golfer has an irrepressible urge to hit with the right hand, then he should seriously consider becoming a hitter and not a swinger.

To those golfers who persist in believing that they need to power the golf swing with the right hand when the club reaches the impact zone (between the 3rd parallel and impact) - while still being a left arm swinger who uses a triple barrel 4:2:3 power accumulator release sequence - consider this swing video of a one-armed swinger.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uUTk7m5PozQ

Note how fast he pivots his torso during the downswing and note how fast he swings his left arm due to an efficient release of PA#4. Also, note how fast his club releases in the mid-downswing due to the passive release of PA#2. How would that golfer use his right arm/hand to get his clubshaft to move faster in the late downswing - considering the efficacy of his sequential release of power accumulator PA#4 and then PA#2? I believe that any attempt to "hit with the right arm/hand" in the late downswing will more likely interfere with his efficient CF-induced club release action and it may actually result in a decrease in clubhead speed. A golfer can definitely hit the ball further using two-arms, compared to using only the left arm alone, but only if the right arm is applying push-pressure at PP#1 in perfect synchrony with the left arm's grip-pulling action (due to an efficient pivot-induced release of PA#4) in the mid-downswing (not late downswing) when left arm speed reaches its maximum speed. At that time point in the downswing, the right elbow is still signficantly bent and any increased push-pressure at PP#1 must be primarily due to an active adduction movement of the right upper arm, which pulls the right forearm flying wedge (consisting of the right forearm and dorsiflexed right wrist/hand) down towards the ball.

Question number 3:

Some golfers think of the left-side of their torso pulling, rather than the right-side of their torso pushing, in their downswing. What is the correct "feeling" that a golfer (who is a swinger) should attempt to acquire (with respect to his torso) during his downswing?

Answer:

I think that is biomechanically incorrect to think of the pivoting torso exhibiting a "left-sided pull-force" rather than a "right-sided push force" in a pivot-driven swinger's action.

I believe that the human torso is an unitary structure, and I believe that a golfer cannot rotate the left-side of the upper torso faster/differently than the right side of the upper torso. I believe that when a golfer rotates the upper torso in space during a pivot-driven downswing, that the entire upper torso rotates as a single unit, and that a golfer cannot rotate the left-side of the upper torso faster than the right-side of the upper torso. Now, although the upper torso has to rotate as single unit, it may "feel" that the left-side is doing the pulling if a golfer is a left-arm swinger (rather than a pivot-driven swinger).

Consider Leslie King's "left-arm swing" swing methodology.

Here is a link to Leslie King's opinions on his method of starting the downswing with a pulling of the left arm downplane while keeping the shoulders back.

http://www.golftoday.co.uk/proshop/tuition/lesson11.html

Here is a copy of Leslie King's instructional statements from that lesson.

Now, maintaining the shoulders in the fully turned position, we simply commence the downward swing of the left hand and arm. That is how the downswing starts, and nothing could be simpler!

I stress again, the SHOULDERS MUST REMAIN IN THE FULLY TURNED POSITION at the beginning of the downswing! The same left foot action that has "charged" the hands with power is enabling us to control the shoulders.

By keeping the shoulders fully turned the left hand and arm can swing freely from the left shoulder, taking the club-head down into the ball on a club line that will result in a swing into and along the line of flight through impact.

Hold your shoulders in the fully turned position as the left hand and arm begins to swing down... this ensures good club line through the ball.

In other words, Leslie King recommends the immediate release of PA#4 at the very start of the downswing - while keeping the shoulders back. There is no pivot-thrust action in his swing methodology and the torso pivots reactively to support the movement of the left arm across the front of the body.When using Leslie King's left arm swing methodology, one is using left shoulder girdle muscles to pull the left arm across the front of the torso.

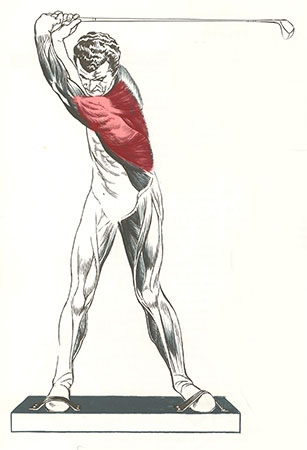

Here is a diagram demonstrating the left-sided torso muscles that are used to pull the left arm across the front of the torso when using Leslie King's left-arm swing style.

Left shoulder girdle muscles - image derived from reference number [8]

The left shoulder girdle muscles (colored in red) are used to pull the left arm away from the chest wall in a left arm swinger's action, and a golfer who uses that swing style will experience a left-sided pulling "feel" on the left-side of the torso.However, when a swinger uses a traditional/conventional pivot-driven swing, the downswing starts from the bottom-up with a lower body shift-rotation movement, and the upper torso moves secondarily. A golfer should "feel" the upper torso being pulled by the lower torso, but the entire upper torso should move as a single cohesive unit when the shoulders start to rotate perpendicularly around the rightwards-tilted spine, and there shouldn't be a "feeling" of the left-side of the upper torso pulling away from the right-side of the upper torso. Instead, there should be a "feeling" that the right shoulder is simultaneously moving downplane while the left shoulder moves away from the chin in the early downswing.

Question number 4:

Do you think that a golfer will hit the ball a longer distance if he uses JimMcLean's X-factor principle?

Answer:

No.

Jim McLean believes that a golfer should restrict the pelvic turn in the backswing, so that a golfer can rotate/coil the upper torso against the resistance of a lower torso's restricted backswing turn. Theoretically, that should allow a golfer to stretch-tighten the mid torso muscles, which should theoretically produce a greater force of upper torso elastic-uncoiling in the downswing. I discussed this issue in great depth in my review paper on Jim Mclean's triple X factor - a critical review.