Critical review: Tyler Ferrell's "Stock Tour Swing"

Click here to go back to the home page.

Introduction:

Tyler Ferrell is a golf instructor, who runs the golfsmartacademy.com website (which offers a monthly subscription service to hundreds of his short videos that cover a variety of topics). New subscribers can get a 7-day free trial before finally deciding whether they want to subscribe to his monthly subscription service. Tyler Ferrell has also published a golf instructional book called "The Stock Tour Swing" and it is available at https://www.amazon.com/Stock-Tour-Swing-Science-Uncover/dp/0999243705 .

In this review paper, I will critically analyse some of Tyler Ferrell's opinions - as expressed in his book and in his videos that are available at his Golf Smart Academy website. I will mainly focus my attention on 5 topics where I significantly disagree with Tyler Ferrell's opinions on golf swing mechanics/biomechanics, and readers of this review paper can independently evaluate our opinions in order to determine whose opinion(s) has the greatest legitimacy - both in terms of sound biomechanical logic and also with respect to the issue as to whether any of the described biomechanical actions actually occur in the golf swings of most professional golfers.

For readers, who only want to read certain topics,

you can click on the relevant links in this introductory section in order to

go directly to that topic.

Topic number 2: The release phase and hand release actions through impact.

Topic number 3: Clubshaft shallowing during the early-mid downswing.

Topic number 1: The topic of clubface-closing during the downswing and an analysis of the "motorcycle move".

Tyler Ferrell is a strong advocate of the "motorcycle move" and he has produced a large number of videos for his Golf Smart Academy website on the topic of the "motorcycle move".

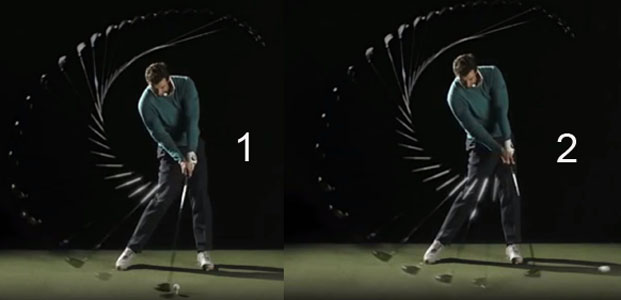

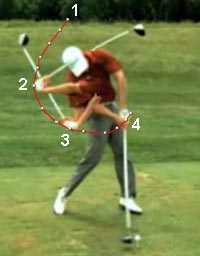

Here is a capture image from one of Tyler Ferrell's videos where he demonstrates the "motorcycle move"

Image 1 shows Tyler Ferrell holding a golf club handle with his left hand as if he were grasping the handle grip of a motorcycle with his left hand. Note that the clubshaft is horizontal to the ground and that the clubshaft is at a roughly 90 degree angle relative to his left forearm, which means that his left wrist is radially deviated (upcocked).

In image 2, he is actively palmar flexing his left wrist while using his right arm/hand to keep the clubshaft stationary so that it does not angulate. Note that the clubface rotates counterclockwise in a clubface closing direction. It would be more accurate to label this maneuver the "reverse motorcyle move" because a motorcyclist usually rotates the motorcyle's handle grip clockwise when twisting the motorcyle's handle grip. However, I will use Tyler Ferrell's "motorcycle move" term in this review paper to describe the true factual reality that palmar flexion of the lead wrist will cause the clubshaft to rotate counterclockwise about its longitudinal axis if the lead wrist is radially deviated, and that it will close the clubface relative to the clubhead arc, and also relative to the watchface area of the back of the left lower forearm, by ~30 degrees if the golfer adopts a weak-neutral lead hand grip.

I have written about the topic of "What effect does lead wrist bowing have on the clubface and clubshaft?" in the following review paper at https://perfectgolfswingreview.net/LeadWristBowing.html and if you look at the capture images of my visual demonstration in that review paper, you will note that I have confirmed the fact that lead wrist bowing twists the club handle about its longitudinal axis so that the clubface will close by ~30 degrees, but only if the lead wrist is radially deviated.

Tyler Ferrell has stated that if a golfer closes the clubface by ~30 degrees relative to the clubhead arc by performing the "motorcycle move" in the early downswing (or even earlier in the late backswing) when the lead wrist is radially deviated that it will allow a golfer to get to the P5.5/P6 position with a clubface that is already closed relative to the clubhead arc by that amount.

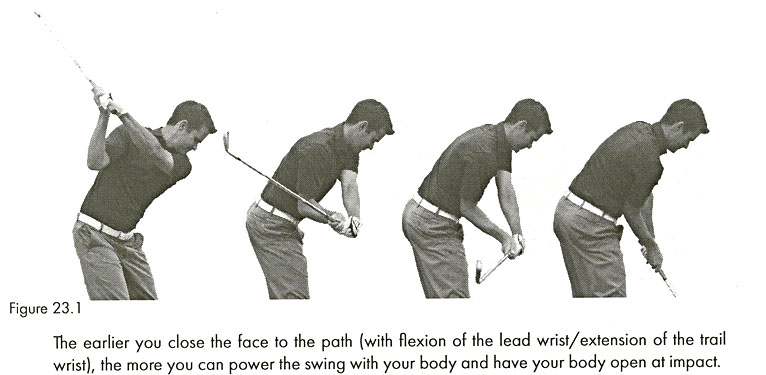

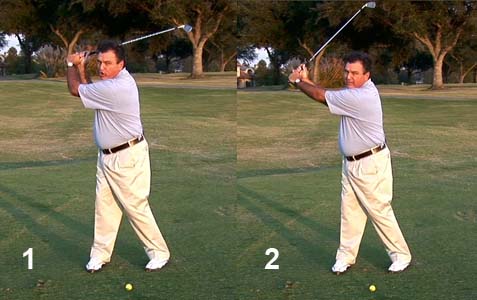

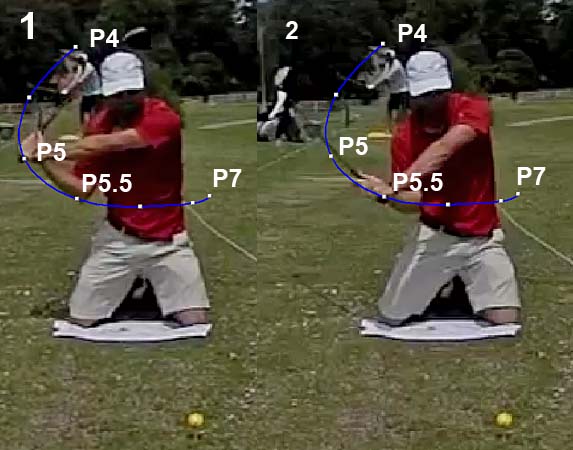

Here are capture images from Tyler Ferrell's "Stock Tour Swing" book where he demonstrates the "motorcycle move".

The first image on the left side shows Tyler Ferrell at his end-backswing position. Note that his lead wrist is slightly cupped, and that his clubface is open to the clubhead arc, but neutral relative to the watchface area on the back of his lead lower forearm (which is expected if a golfer adopts a weak-neutral lead hand grip strength). Note that his lead wrist is radially deviated and that the clubshaft is at a ~90 degree angle relative to his lead forearm.

The second image shows Tyler Ferrell at his P5.5 position. Note that his lead wrist is overtly bowed (palmar flexed) and that it closes the clubface relative to his clubhead arc by ~ 20-30 degrees because the lead wrist bowing maneuver that he is performing between P4 => P5.5 is happening when his lead wrist is radially deviated. Note that the clubface is closed relative to his clubhead arc, and also closed relative to the watchface area on the back of his lead lower forearm, by ~20-30 degrees at his P5.5 position (and also at his P6 position in the third image).

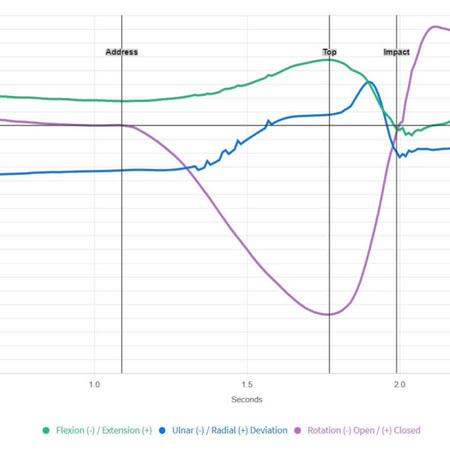

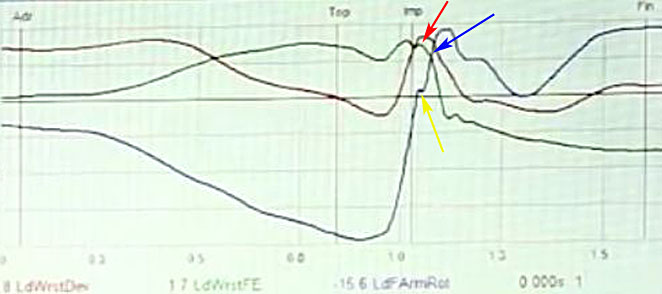

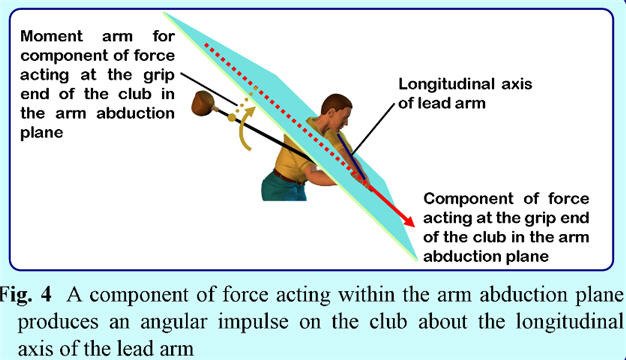

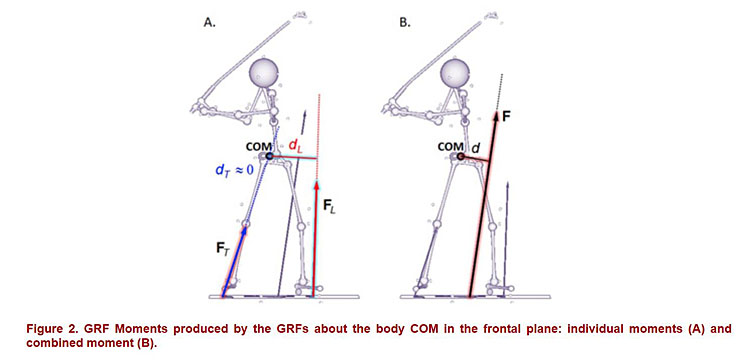

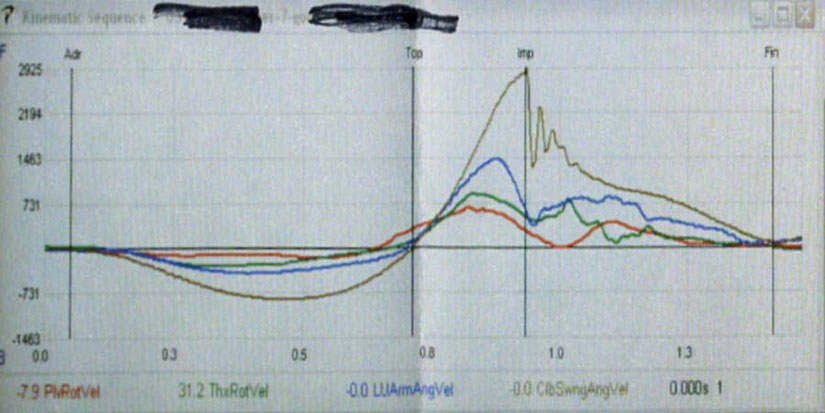

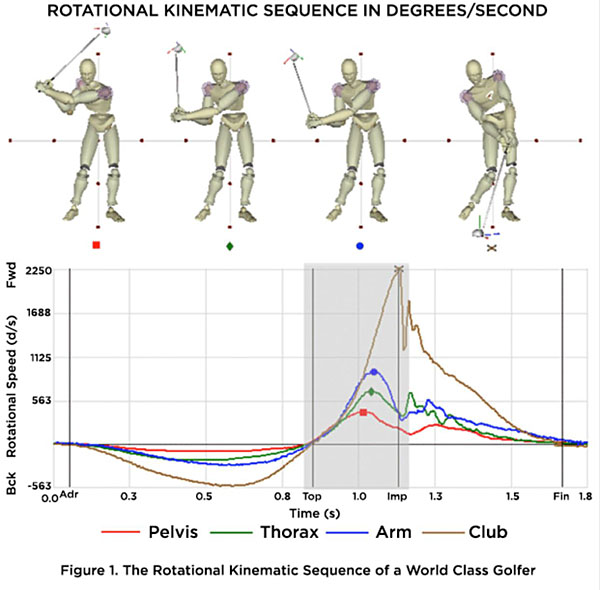

What is the implication of that true factual reality? Tyler Ferrell has implied that early clubface closing of ~30 degrees secondary to the use of a "motorcycle move" maneuver (that is performed during the early-mid downswing) means that a golfer can simply rotate his torso counterclockwise into impact without having to use any further clubface closing in the later downswing secondary to the use of lead forearm supination (which is called a PA#3 release action in TGM terminology). To support his opinion, Tyler Ferrell presented the following comparative handle twist velocity graphs in one of his Golf Smart Academy videos.

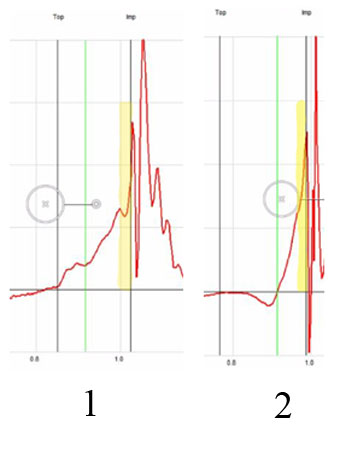

Composite image created from two copied graphs.

The red graph is a measure of the handle twist velocity of the golf club handle during the downswing. The vertical black line labelled "top" represents the end-backswing position and the vertical black line labelled "imp" represents the impact position, and the downswing happens between the two vertical black lines.

Image 1 shows the handle twist velocity graph of a pro golfer who apparently uses the "motorcycle move" in the early downswing. Note that the graph shows a low level of handle twist velocity happening in the early downswing between the vertical "top" black line and the green vertical line, and that is presumably due to the "motorcycle move" maneuver.

Image 2 shows the handle twist velocity graph of a skilled amateur golfer who does not use the "motorcycle move" maneuver. Note that his handle twist velocity graph does not rise above the zero horizontal black line in his early downswing. Note that his handle twist velocity starts to increase in the mid-downswing and that it then continues to increase in a smooth, non-interrupted manner all the way to impact, reaching its maximum axial twist velocity at impact.

Now, look again at image 1's handle twist velocity graph. Note that the handle twist velocity is not fast in the mid-downswing, but it does increase very rapidly in velocity just before impact (see the yellow-colored zone). In fact, if you look at the handle twist velocity graph near/at impact in image 1 it is just as fast as the handle twist velocity graph seen near/at impact in image 2 (see the yellow-colored zone). Why is the handle twist velocity so fast just before impact in image 1 - thereby contradicting Tyler Ferrell's claim that using a "motorcycle move" maneuver in the early downswing means that a golfer will not have to twist the club handle very fast in the later downswing near impact? The answer is related to the fact that the golfer is maintaining a bowed lead wrist throughout the entire downswing into the early followthrough, and it is causally due to the fact that maintaining a bowed lead wrist into the later downswing, when the lead wrist becomes increasingly ulnar deviated, causes clubshaft angulation without clubface closing. I discussed this "clubshaft angulation effect due to lead wrist bowing happening when the lead wrist is ulnar-deviated" phenomenon in great detail in my review paper called "What effect does lead wrist bowing have on the clubface and clubshaft?"

I believe that many golf instructors do not understand that maintaining a bowed lead wrist "motorcycle move" maneuver into the later downswing will cause backwards angulation of the clubshaft relative to the bowed lead wrist/hand, so that the golfer will approach impact with a lot of forward shaft lean (where the lead hand is well ahead of the clubhead).

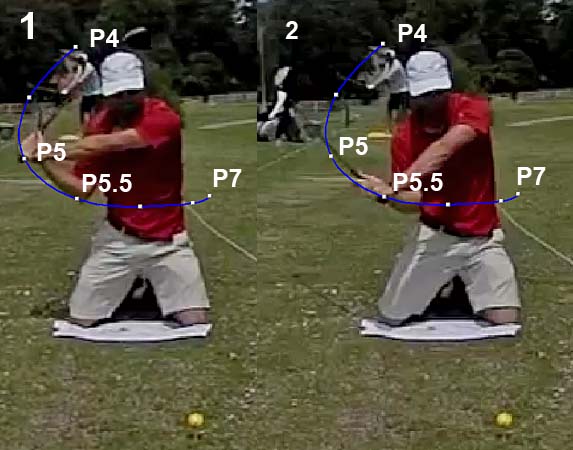

Here is an example - featuring Collin Morikawa.

Image 1 shows Collin Morikawa at his P6.7 position and image 2 shows him at impact.

Note that Collin Morikawa has a markedly bowed lead wrist that angles his clubshaft back away from the target relative to his lead hand. Now, although Collin Morikawa closed his clubface relative to his clubhead arc by ~30 degrees by bowing his lead wrist at his P4 position when his lead wrist was radially deviated, his clubface is still open relative to the ball-target line at his P6.7 position because his clubshaft is angled so much backwards relative to his bowed lead wrist/hand. Look at how much Collin Morikawa has to rotate his lead hand, and therefore his clubface, counterclockwise between P6.7 => impact - i) by looking at the degree of counterclockwise rotation of the back of his lead hand, or ii) by looking at the degree of counterclockwise rotation of his lower radial bone in his lower lead forearm, or iii) by looking at the degree of counterclockwise rotation of the watchface area on the back of his lead lower forearm. To get a square clubface by impact, Collin Morikawa has to use a finite amount of counterclockwise rotation of his lead humerus and a finite amount of lead forearm supination between P6.7 => P7, and Tyler Ferrell is not taking that fact into account. Note that Collin Morikawa's lead hand has already reached the ball position by P6.7 and that there is only about 2" of targetwards travel of his lead hand happening between P6.7 => impact. That means that the degree of counterclockwise rotation of his clubshaft (due to lead arm/forearm counterclockwise rotation) happening per unit amount of lead hand travel distance is going to be larger near impact, which will likely result in a larger clubface ROC near impact - even if the overall amount of counterclockwise rotation of his clubshaft is smaller in amount between P6 => P7 due to the fact that his clubface is already closed relative to his clubhead arc by ~30 degrees at the P6 position.

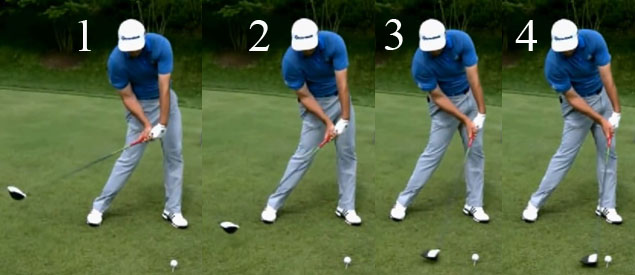

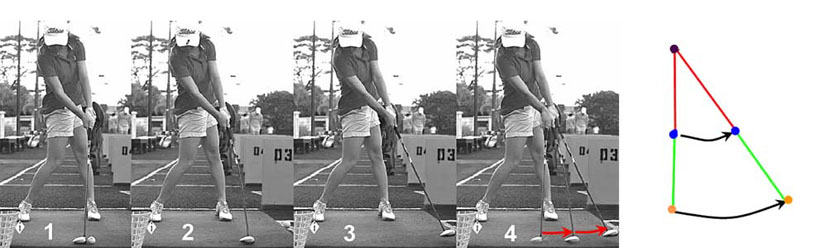

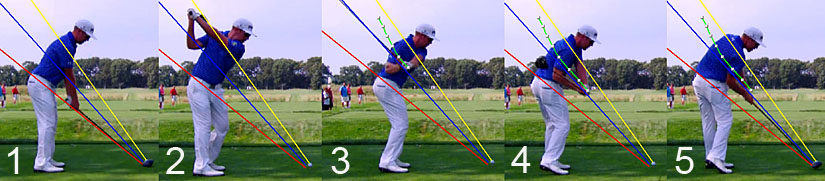

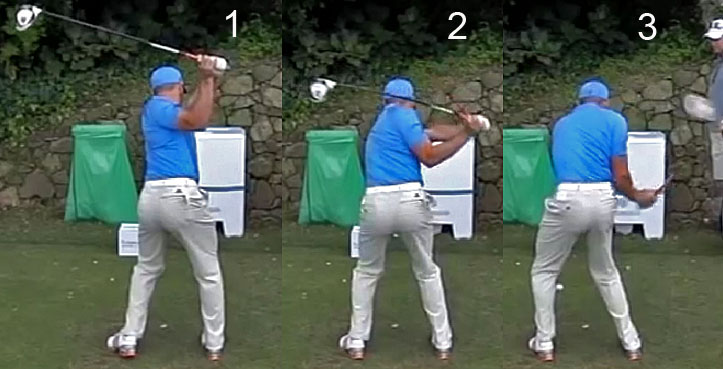

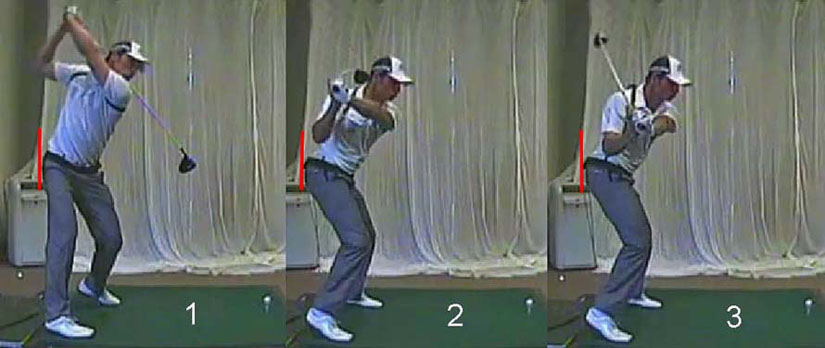

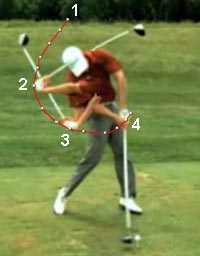

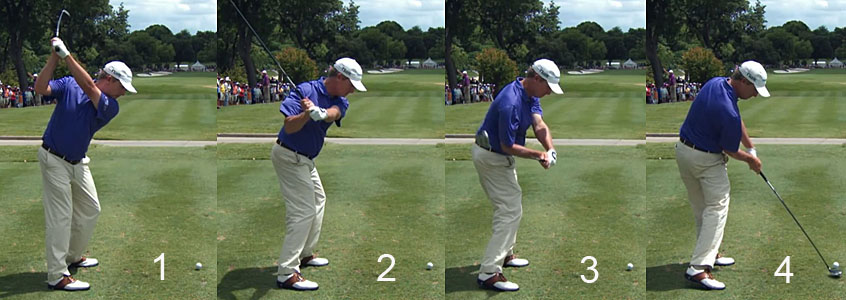

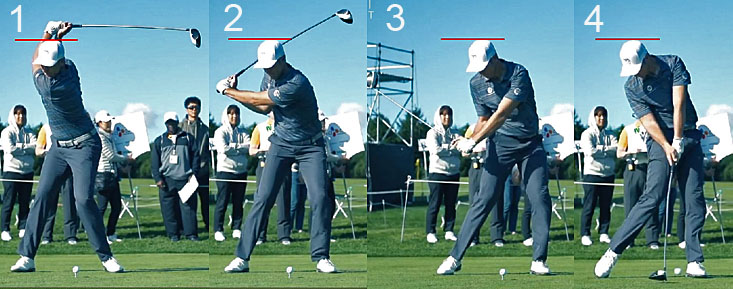

Jon Rahm is a prototypical example of a golfer who uses the bowed lead wrist "motorcycle move" technique, and here are capture images showing how he uses the "motorcycle move" during his early-mid downswing golf swing action.

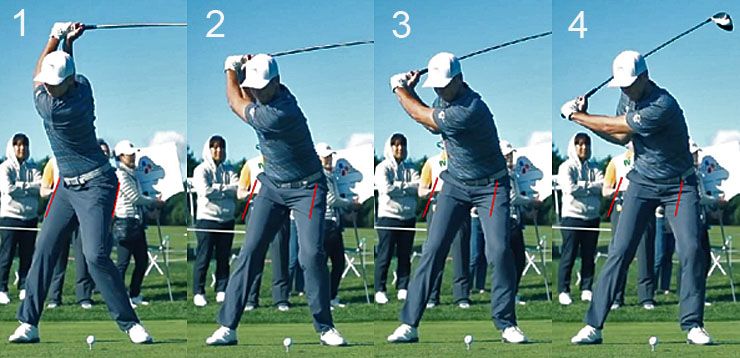

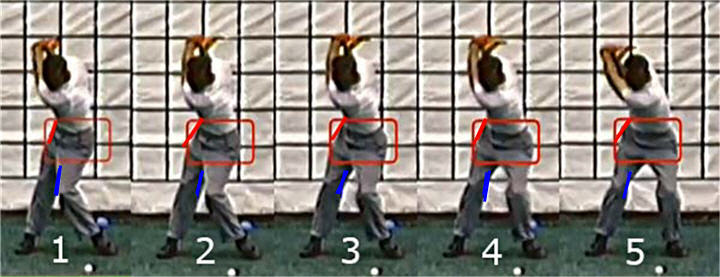

Image 1 is at the P4 position, image 2 is at the P5 position, image 3 is at the P5.5 position and image 4 is at the P6 position.

Note that Jon Rahm bowed his lead wrist during his backswing action, and that it caused his clubface to be slightly closed relative to his clubhead arc, and also relative to the watchface area on the back of his lead lower forearm, at the P4 position.

Note that the degree of lead wrist bowing is less at the P5 position, but it then increases significantly in amount between the P5 => P6 positions due to Jon Rahm's use of the "combined lead wrist palmar flexion + early lead forearm supination" maneuver. Note that Jon Rahm's clubface is closed by >30 degrees relative to his clubhead arc, and also relative to the watchface area on the back of his lead lower forearm, at the P6 position.

Now, although proponents of the "motorcycle move" maneuver (like Tyler Ferrell) believe that early clubface closing due to use of the "motorcycle move" between P4 => P6 implies that the golfer can simply turn his body into impact without having to rotate the lead forearm counterclockwise during the later downswing, the true "real life" reality does not support their opinion.

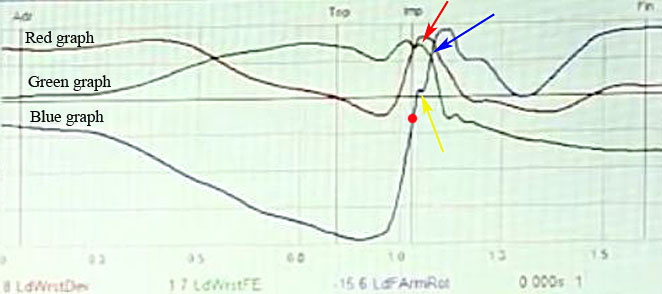

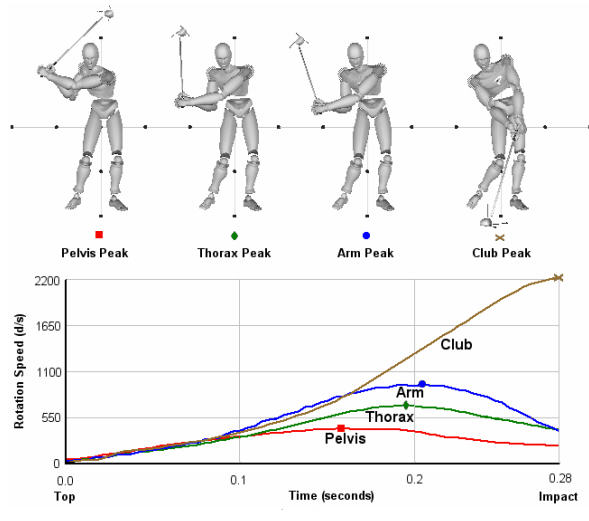

Here is a copy of Jon Rahm's 3D graphs.

The green graph represents Jon Rahm's lead wrist flexion-extension graph. Note that Jon Rahm's lead wrist is bowed at the P4 position. Then, note that his degree of lead wrist bowing decreases slightly in the early downswing before increasing again in the later downswing and that he reaches impact with a markedly bowed lead wrist.

The blue graph represents Jon Rahm's lead forearm supination-pronation graph. Note that Jon Rahm's lead forearm is pronated at his P4 position, and that his lead forearm pronates slightly more during his early-mid downswing when he shallows his clubshaft between P4 => P6. Then, note how much, and how rapidly, Jon Rahm supinates his lead forearm in his later downswing after P6. The reason why Jon Rahm still has to use a large amount of lead forearm supination in his later downswing in order to square his clubface by impact is due to the fact that his marked amount of lead wrist bowing, which is happening between P6 => P7, angles his clubshaft backwards away from the target and thereby opens the clubface relative to his ball-target line - and like Collin Morikawa, he needs to rotate his lead hand counterclockwise by a significant amount between P6.5 => P7 in order to get his clubface square to the ball-target line by impact.

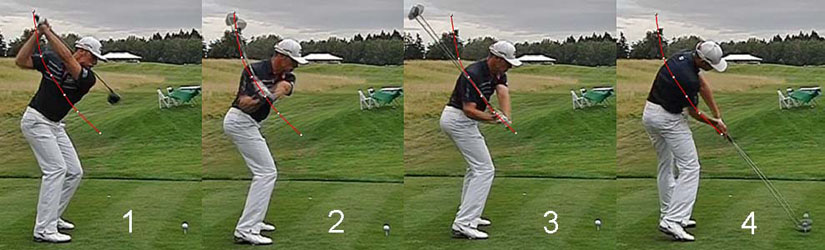

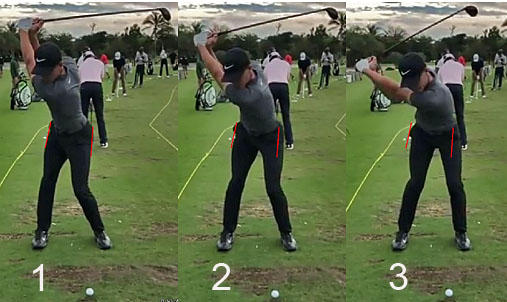

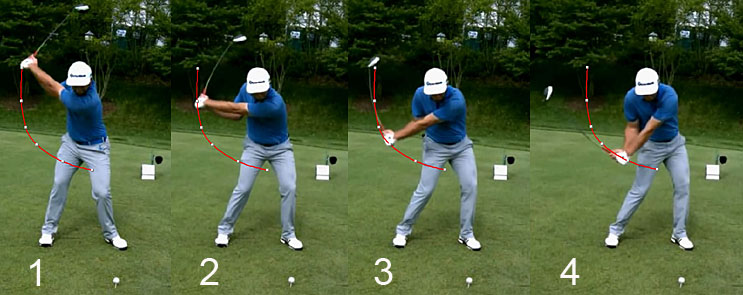

Here are capture images of Jon Rahm's late downswing action.

Image 1 is at the P6.2 position, image 2 is at the P6.5 position, image 3 is at the P6.8 position and image 4 is at impact.

At the P6.5 position, Jon Rahm's clubface is presumably closed relative to his clubhead arc by ~30 degrees because he performed the "motorcycle move" in his backswing and early-mid downswing when his lead wrist was radially deviated. However, his clubface is still very open relative to his ball-target line because he has such a large degree of backwards clubshaft angulation - note that his lead hand has already reached the ball position while his clubhead is still about 30" away from impact. Note that his lead hand only moves targetwards by a few inches between P6.5 => P7 and during that time period his clubface has to rotate counterclockwise by a significant amount in order for the clubface to become square to the ball-target line at impact. It is therefore not surprising that Jon Rahm's 3D lead forearm rotation graph shows a large amount of lead forearm supination rapidly happening between P6.5 => P7.

Another error that Tyler Ferrell makes with respect to his opinions regarding the "motorcycle move" is his opinion that a pro golfer must be using the "motorcycle move" if his lead wrist becomes less extended during his early/mid downswing.

Watch this Tyler Ferrell video called "Flexing Your Wrist - Golf Club Face Motorcycle Move", which is available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MNpOGqOvOEE&t=56s

In that video, Tyler Ferrell states that a golfer can perform the "motorcycle move" during the i) backswing, ii) early-mid downswing or iii) late downswing.

As an example of a pro golfer who Tyler Ferrell believes is performing the "motorcycle move" during the early-mid downswing between P4 => P6, Tyler Ferrell uses Henrik Stenson as a prototypical example. However, what is the fundamental fact justifying Tyler Ferrell's opinion that Henrik Stenson is using the "motorcycle move" during the P4 => P6 time period? Tyler Ferrell simply asserts in his video that Henrik Stenson's lead wrist is more extended at the P4 position than it is at the P6 position, which only means that his lead wrist is moving in the direction of palmar flexion (lead wrist bowing) during the P4 => P6 time period. However, although Tyler Ferrell is correct to assert that Henrik Stenson's lead wrist is less extended at the P6 position than it is at the P4 position, that does not necessarily mean that Henrik Stenson is using the "motorcycle move". Tyler Ferrell would also have to demonstrate that Henrik Stenson's clubface is closing relative to his clubhead arc, and also relative to the watchface area on the back of his lead lower forearm, between P4 => P6.

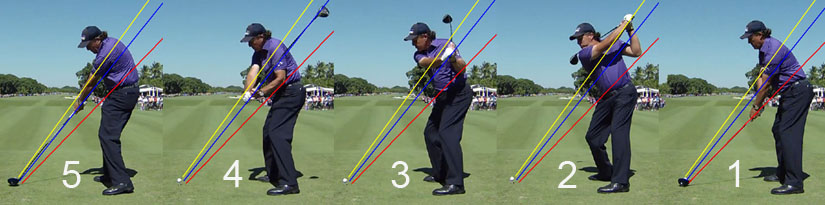

Here are comparative capture images of Tyler Ferrell's and Henrik Stenson's mid downswing action.

Image 1 shows Tyler Ferrell at the P5.5 position, and images 2 and 3 show Henrik Stenson at the P5.5 position (viewed from two different viewing perspectives).

Note that Tyler Ferrell is using the "motorcycle move" based on two clearly observable facts - i) his lead wrist is overtly bowed and ii) his clubface is closing by ~20 - 30 degrees relative to his clubhead arc, and also relative to the watchface area on the back of his lead lower forearm.

Note that Henrik Stenson still has a slightly cupped lead wrist at P5.5, and although it is less cupped at P5.5 than it was at P4, it is not overtly bowed. More importantly, note that his clubface is not closing relative to his clubhead arc or relative to the watchface area on the back of his lead lower forearm - so he cannot possibly be using the "motorcycle move" like Tyler Ferrell.

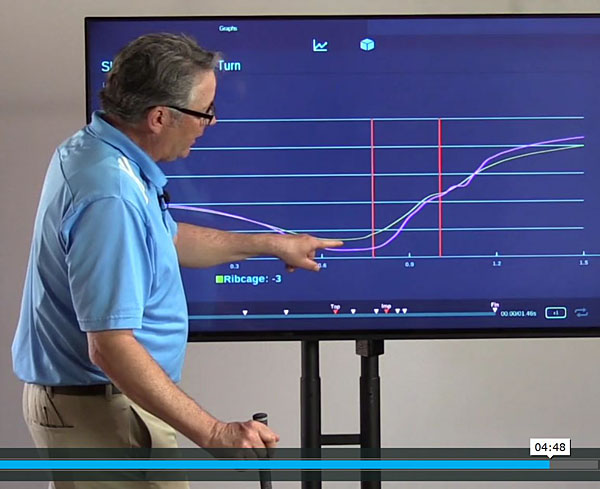

Here is a HackMotion 3D graph of Henrik Stenson's downswing action.

The downswing action happens between the vertical black line labelled "top" and the vertical black line labelled "impact".

The green graph is Henrik Stenson's lead wrist flexion-extension graph. Note that Henrik Stenson's lead wrist is extended at his P4 position and that it becomes progressively less extended during his downswing to eventually become borderline palmar flexed at impact.

Now, although Henrik Stenson's lead wrist is steadily moving in the direction of less lead wrist extension (which is the same as saying that it is moving steadily in the direction of lead wrist palmar flexion) throughout his entire downswing, that does not mean that Henrik Stenson is using the "motorcycle move" golf swing technique. In reality, Henrik Stenson is actually using the intact LFFW/GFLW golf swing technique, which I described in great detail in my review paper called "What effect does lead wrist bowing have on the clubface and clubshaft?".

A key point about understanding the intact LFFW/GFLW golf swing technique is understanding the natural biomechanical phenomenon where the lead wrist of a golfer, who uses a weak-neutral lead hand grip strength, will automatically/naturally becomes less extended as it moves from being radially deviated at the P4 position to becoming more ulnar deviated in the later downswing between P6.5 => P7.

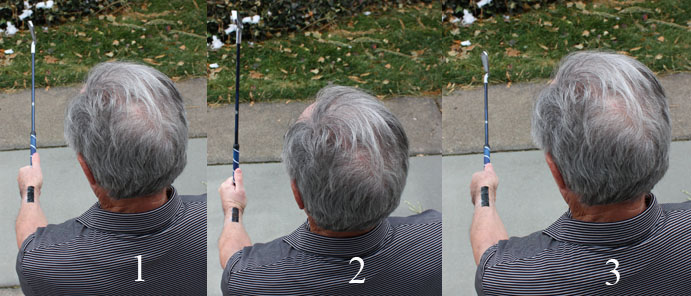

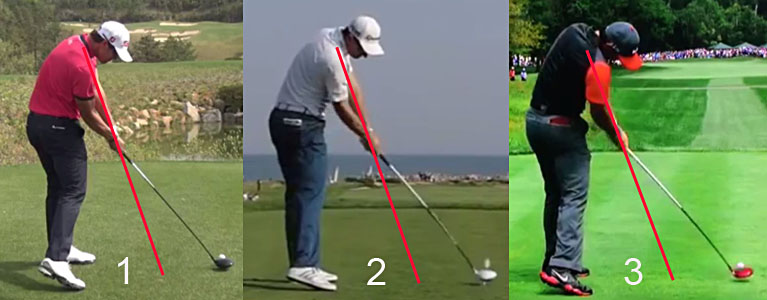

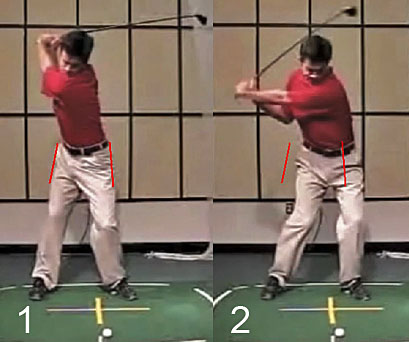

Here is a capture image from my review paper showing that natural biomechanical phenomenon.

In image 1, I (the author of this review paper) am holding a short golf club in my left hand using a weak left hand grip strength. I have taped a 3" piece of black tape over my lower radial bone at the level of my lower left forearm. Note that the clubshaft is straight-in-line with that black taped area of my left lower forearm, which means that I have an intact LFFW (left forearm flying wedge). Note that the clubface is also straight-in-line with my left lower forearm, which means that it is neutral and not open/closed relative to my left lower forearm. Note that my left wrist is slightly cupped (dorsiflexed), which is biomechanically expected if I adopt a weak lead hand grip strength and a low palmar lead hand grip position. Now, although my left wrist does not look anatomically flat, it is geometrically flat (= where the clubshaft is straight-line-aligned with the black-taped area of my lower lead forearm), and that geometrical straight-line relationship between the clubshaft and my lower lead forearm defines the term GFLW (geometrically flat left wrist).

In image 2, I am radially deviating my left wrist so that the clubshaft becomes roughly perpendicular to my left forearm (simulating the P4 position's left wrist alignment in the plane of ulnar-radial deviation). Note that the degree of left wrist cupping (dorsiflexion) increases even though I still have an intact LFFW/GFLW alignment and note that the clubface still remains neutral relative to my left forearm.

In image 3, I am ulnar deviating my left wrist (simulating my impact position's left wrist alignment in terms of its degree of ulnar deviation in the plane of ulnar-radial deviation). Note that my left wrist becomes less extended and borderline palmar flexed (anatomically flat) even though I still have an intact LFFW/GFLW alignment and the clubface still remains neutral relative to my left forearm.

In other words, although my left wrist changed from being frankly extended when it is radially deviated to becoming borderline palmar flexed when it is ulnar deviated, the changing degree of left wrist extension does not disrupt my intact LFFW/GFLW alignment and it does not close the clubface relative to the black-taped area of my left lower forearm. If you want to better understand the biomechanics underlying the intact LFFW/GFLW golf swing technique (as used by Henrik Stenson, Justin Rose, Adam Scott and Tiger Woods), then I would recommend that you read the relevant section of my review paper.

I previously mentioned that Tyler Ferrell stated in his video called "Flexing Your Wrist - Golf Club Face Motorcycle Move" that it possible to perform the "motorcycle move" during either the late backswing, early-mid downswing or late downswing. Tyler Ferrell's conceptual idea of the "motorcycle move" is the idea that an active lead wrist bowing maneuver closes the clubface relative to the clubhead arc. I have already agreed that it is possible to close the clubface relative to the clubhead arc by bowing the lead wrist during the backswing, or early-mid downswing, when the lead wrist is radially deviated. However, I don't agree that it is possible to significantly close the clubface relative to the clubhead arc in the later downswing (after P6) when the lead wrist becomes significantly ulnar deviated. Under those conditions, lead wrist bowing is far more likely to angle the clubshaft backwards away from the target relative to the lead wrist/hand without closing the clubface relative to the clubhead arc. In his "Flexing Your Wrist - Golf Club Face Motorcycle Move" video, Tyler Ferrell uses Rory Sabbatini as an example of a pro golfer who he believes is using the "motorcycle move" in his late downswing.

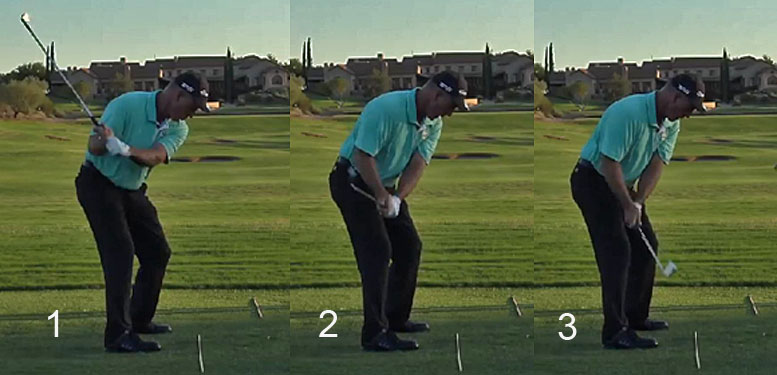

Here are capture images of Rory Sabbatini's late downswing action.

Image 1 is at the P6 position and image 2 is at impact.

At the P6 position, Rory Sabbatini does not have a bowed lead wrist and his lead wrist is slightly cupped. Note that his clubface is not closed relative to his clubhead arc at the P6 position.

Between P6 => P7, Rory Sabbatini starts to bow his lead wrist so that he reaches impact with a slightly bowed lead wrist. What effect does bowing his lead wrist between P6 => P7 have on his clubface and clubshaft? I believe that bowing his lead wrist during his later downswing between P6 => P7, when his lead wrist is becoming increasingly ulnar deviated, will allow him to reach impact with a finite amount of forward shaft lean (which is desirable), but I do not believe that it will close his clubface relative to his clubhead arc in such a way that it will decrease the amount of lead forearm supination required to get a square clubface by impact. Note how much Rory Sabbatini is rotating the watchface area of his lead lower forearm, and therefore the back of his lead hand, counterclockwise between P6 => P7. I believe that it is mainly due to a lead forearm supinatory motion, and I think that there is no reason to believe that he is using less lead forearm supination as a result of bowing his lead wrist during that same P6 => P7 time period. Tyler Ferrell has presented no evidence that bowing the lead wrist in the later downswing between P6 => P7 (in a golfer who uses a weak-neutral lead hand grip strength) will decrease the amount of lead forearm supination required in the later downswing in order to square the clubface by impact!

As a second example of a pro golfer who Tyler Ferrell believes is using the "motorcycle move" in the later downswing, Tyler Ferrell uses the example of John Senden.

Watch Tyler Ferrell's "Flexing Your Wrist - Golf Club Face Motorcycle Move" video between the 14:16 - 14:59 minute time points where he claims that John Senden is using the "motorcycle move" in his late downswing just before impact.

Here are capture images (from that video) of John Senden's late downswing action.

Image 1 is the P6 position, image 2 is at the ~P6.5 position, image 3 is at the ~P6.8 position and image 4 is at impact.

Note that John Senden's lead wrist is cupped at the P6 position and less cupped at impact, which means that his lead wrist is moving in the direction of lead wrist palmar flexion. However, the fact that John Senden's lead wrist is becoming less extended between P6 => P7 does not mean that he is using the "motorcycle move", which Tyler Ferrell believes is primarily used to close the clubface relative to the clubhead arc.

Look more carefully at those capture images and you will note that John Senden, who uses a very strong lead hand grip strength, is not rotating his lower lead forearm, and therefore the back of his lead hand, counterclockwise very much between P6 => P7 and that he reaches impact with the ulnar border of his lead hand facing the target while the back of his lead wrist/hand is facing the ball-target line. If the back of his lead wrist/hand is facing the ball-target line, and if it is parallel to the functional swingplane, in the later downswing when he starts to bow his lead wrist, then that lead wrist bowing phenomenon will primarily change the angle of his clubshaft in the VSP (vertical swingplane) which is perpendicular to the direction of his clubhead arc, and it will not produce forward shaft lean or close the clubface relative to the clubhead arc.

A pro golfer, who adopts a very strong lead hand grip strength at address, already has his clubface closed relative to the watchface area of his lead lower forearm and he therefore should have no incentive to use an additional clubface-closing maneuver (like the "motorcycle move") to close the clubface even more relative to his clubhead arc during his downswing action. Also, if he does increasingly bow his lead wrist during his later downswing between P6 => P7 it will not close the clubface relative to his clubhead arc for two reasons. First of all, if lead wrist bowing happens in the later downswing, when the lead wrist becomes increasingly ulnar deviated, it only changes the clubshaft angle (relative to the lead forearm) and it does not close the clubface relative to the clubhead arc. Secondly, if lead wrist bowing happening between P6 => P7 did actually cause the clubface to close slightly relative to the watchface area of his lead lower forearm between P6 => P7, that changing clubface angle would be happening perpendicular to the targetwards direction of the clubhead arc, and not parallel to the direction of the clubhead arc - and it would more likely affect the clubface's dynamic loft rather than have any closing effect on the clubface relative to the targetwards direction of the clubhead arc! I think that it is a major mistake to claim that a pro golfer, who uses a very strong lead hand grip strength, can effectively use the "motorcycle move" in the later downswing in order to help close the clubface relative to the clubhead arc, and thereby reduce the amount of lead forearm supination required during the late downswing's PA#3 release action (where the required amount of lead forearm supination is inversely proportional to a pro golfer's lead hand's grip strength).

In conclusion, I agree with Tyler Ferrell's opinion that if a pro golfer, who uses a weak-neutral lead hand grip strength, performs the "motorcycle" move in the late backswing or early-mid downswing (when the lead wrist is radially deviated), that it will close the clubface relative to the clubhead arc, and also relative to the watchface area on the back of the lead lower forearm, by ~ 20 - 30 degrees at the P6 position. However, that clubface closing benefit is offset by the fact that if a pro golfer maintains a significantly bowed lead wrist between P6 => P7 that it will angle the clubshaft backwards relative to the lead forearm and that clubshaft angulation phenomenon will have a clubface opening effect relative to the ball-target line, which means that the golfer will still likely have to use a lot of lead forearm supination in his later downswing, and the handle twist velocity near impact is also likely to still be very rapid. However, although I think that using a bowed lead wrist golf swing technique (rather than the intact LFFW/GFLW golf swing technique) has negligible benefit from a clubface closing perspective, I do think that the bowed lead wrist technique has other major benefits - i) it naturally results in forward shaft lean at impact; ii) the bowed lead wrist is likely to be more mechanically stable than a GFLW at impact and through impact; and iii) it is very conducive to more efficiently executing a DH-hand release action through the immediate impact zone between P7 => P7.2+. I discussed these three major benefits in my review paper on this topic.

Topic number 2: The release phase and hand release actions through impact.

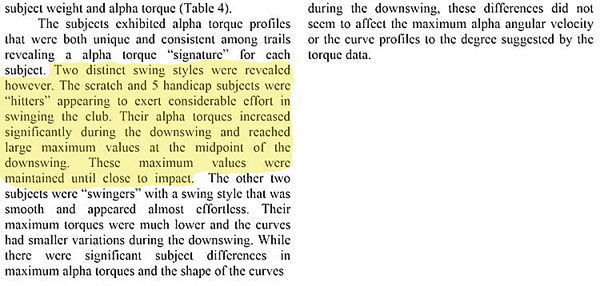

Tyler Ferrell describes two phases in his recommended golf swing action - a transition phase between P4 and P5.5 (which is the swing power production phase) and a release phase between P5.5 and P8 during which time period the arms and club are released. Tyler Ferrell does not divide the release phase into a pre-impact phase and a post-impact phase, and he does not talk about a separate PA#2 release phase (club release phase) and a separate PA#3 release phase (clubface-closing phase due to left forearm supination). He simply states that the release phase starts with a bent right elbow, bent right wrist and a radially deviated left wrist at P5.5 and he states that during the release phase between P5.5 and P8 the two arms will fully straighten and that the "arm straightening/extending" phenomenon will naturally cause the club to release and the left forearm to maximally supinate.

Consider Tyler Ferrell's description of the release phase in the following you-tube video - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9lgMWCrhyIU

Tyler Ferrell states in the video that as the arms extend fully during the release phase that the arm extension phenomenon should fully supinate the left forearm and fully pronate the right forearm.

Capture image from that video featuring Tyler Ferrell.

Image 1 is at the start of the release phase where the left wrist is

radially deviated and the left forearm is pronated, while the right elbow

and right wrist are both bent and the right forearm is supinated. Note that

the clubface is facing skywards.

Image 2 is at the end of the release phase where the right elbow has fully straightened and where the right forearm has fully pronated over a fully supinated left forearm. Note that the left palm is facing skywards and note that the clubshaft has bypassed his left arm (from an angular rotational perspective) secondary to the left forearm supination phenomenon. Note that the clubface has markedly rotated and it is facing the ground. Note that the right wrist has fully straightened and that the fully pronating right forearm has caused the right palm to roll over the fully supinated left hand so that the right palm faces the ground (while the left palm faces the sky).

Tyler Ferrell often emphasises his "opinion" that he wants the left forearm to fully supinate after impact when he discusses his "release phase" ideology and he uses the term "maxing-out" left forearm supination to describe the biomechanical phenomenon where the left forearm continues to supinate to its maximum degree during the followthrough phase between impact and P8.

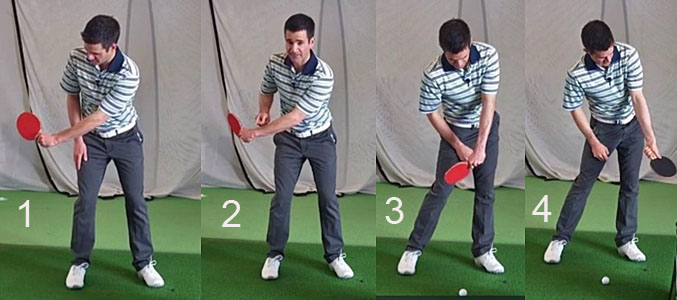

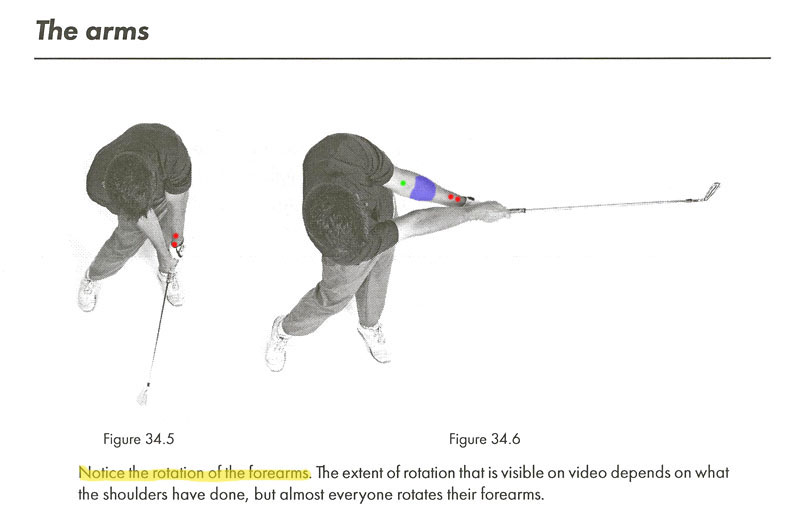

Consider these capture images from a Tyler Ferrell video that is available at his golfsmartacademy.com website - called "Single Arm Ping Pong Paddle Release Training" - where he performs a "release phase" drill using a ping pong paddle.

Image 1 is at the end of the transition phase - where the

left wrist is radially deviated and where he has a GFLW (slightly cupped left

wrist) and where the face of the paddle is open relative to the paddle path.

Note that his left forearm is pronated so that the watchface area of his

left lower forearm and the back of his left hand face partially skywards.

Image 2 shows how he is using a "motorcycle move" (twistaway maneuver) to close the paddle's face relative to the paddle's path.

Image 3 shows the start of the release phase where the left wrist moves from radial deviation to ulnar deviation and that causes the paddle to catch up to the straight left arm by impact - thereby simulating the release of PA#2.

Image 4 shows how he fully supinates his left forearm through the impact zone between P7 and P7.2 and that causes the ping pong paddle to roll over so that the red colored front of the paddle (which was facing partially skywards in image 1) is now partially facing the ground in image 2. Note that the watchface area of his left lower forearm and the back of his left hand are facing the camera (and partially skywards) in image 3 and then facing away from the camera (and partially groundwards) in image 4. One can understand why Tyler Ferrell uses the term "maxing-out" to describe the marked degree of left forearm supination that happens through impact in his recommended hand release pattern - when you consider the huge difference in his lower left forearm's rotational orientation between image 3 and image 4.

Tyler Ferrell believes that the left forearm should start to supinate during the late downswing's pre-impact time period and that it should continue to supinate in an uninterrupted (continuous/non-stop) manner through impact so that it can become fully supinated by P8, and that opinion is expressed in the following you-tube video called "Should You Supinate in the Golf Swing Release", which is available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mG5vqemOzyg&t=724s .

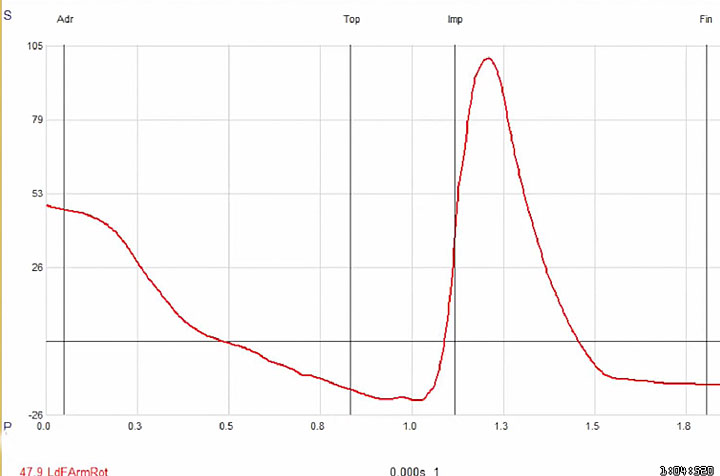

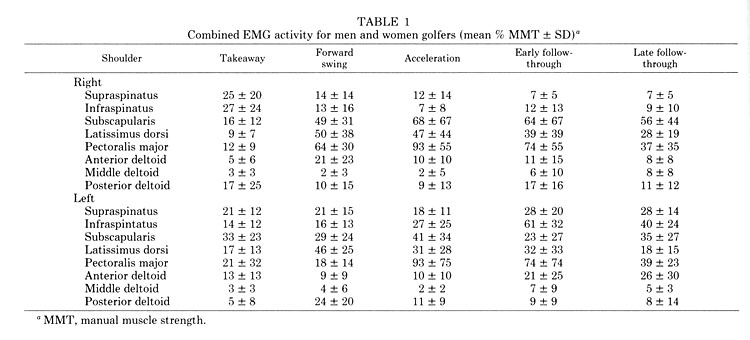

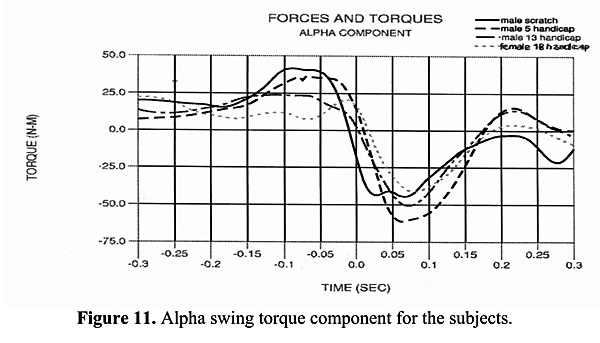

In that video, Tyler Ferrell uses the following 3-D graph of left forearm supination (apparently captured from a professional golfer) to demonstrate what he believes should optimally happen with respect to the left forearm during the "release phase" of the golf swing.

Supination is above the horizontal black zero line, and pronation is below

the horizontal black line. "Top" is the end-backswing position and "Imp" is

impact.

The red graph shows the amount of left forearm supination happening in the late downswing and early followthrough - between the two time points when the red graph has a nadir pre-impact and a peak post-impact. Note that the maximum degree of supination happens after impact and it is ~90 degrees in magnitude, and that it reflects Tyler Ferrell's opinion that a golfer should "max-out" his degree of left forearm supination between impact and P8. The slope of the red graph between these two points is reflective of the speed of left forearm supination and one can see that it is happening very fast through impact, and it is also happening in a continuously uninterrupted manner. This red graph apparently represents the rotational pattern of left forearm supination that Tyler Ferrell recommends for his "release phase".

What would this "uninterrupted left forearm supination" rotational pattern - where the left forearm continues to supinate rapidly in an uninterrupted manner through impact - visually look like in a "real life" golf swing if performed by a professional golfer?

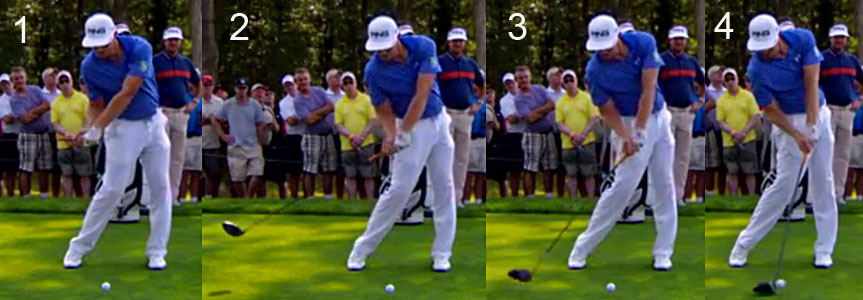

I think that it would look like Luke Donald's hand release pattern - as depicted in the following series of capture images from a face-on swing video of Luke Donald's driver swing.

Image 1 is at impact, image 2 is at about P7.4 and image 3 is at about P7.7.

Note that the clubshaft is straight-in-line with his left arm at impact (image 1). Note that the back of his left hand and the watchface area of his left lower forearm is partially facing the camera in image 1.

Note how much the back of his left hand and the watchface area of his left lower forearm has rotated counterclockwise between image 1 and image 2 and that is primarily due to an uninterrupted left forearm supination phenomenon happening between impact and P7.4. Note that the fast and uninterrupted "left forearm supination" phenomenon has caused his clubshaft to bypass his left arm/forearm (from an angular rotational perspective) by P7.4. Note how he straightens his right arm and right wrist, and how he fully pronates his right forearm during his followthrough so that his right palm is rotating clockwise at roughly the same speed as his left palm is rotating counterclockwise.

Note how he continues to supinate his left forearm between P7.4 (image 2) and P7.7 (image 3) and note how it causes his clubshaft to bypass his left arm to an even greater degree. Note that Luke Donald has seemingly "maxed-out" his left forearm supination by P7.7, which is slightly faster than what would happen if he only "maxed-out" his left forearm supination by P8.

Most importantly, look at his clubface, and note how it closes very fast (relative to his clubhead arc) between impact and P7.7 - and also note that the speed/magnitude of his clubface-closure is directly proportional to the speed/magnitude of his left forearm supination motion that is happening during that P7 => P7.7 time period.

In his "Should You Supinate in the Golf Swing Release" video, Tyler Ferrell also features the golfer Tommy Fleetwood as an example of a golfer who also "maxes-out" his degree of left forearm supination by the P8 position. Does that mean that Tommy Fleetwood is continuously supinating his left forearm in an uninterrupted manner during his early followthrough between P7 and P7.4 - as depicted in that 3-D graph?

Let's analyse capture images of Tommy Fleetwood's P7 => P8 followthrough action from that driver swing featured in the video.

Image 1 is at impact, image 2 is at P7.4, image 3 is at P7.7 and image 4 is at P8.

Note that Tommy Fleetwood's clubshaft is straight-in-line with his left arm at impact and also at P7.4. That phenomenon - where the clubshaft does not bypass the left arm (from an angular rotational perspective) between impact and P7.4 - is characteristic of a drive-hold (DH) hand release action, and it is very different to the non-DH hand release action used by Luke Donald. What are the primary biomechanical characteristics that make a DH-hand release action possible between impact and P7.4+? The correct answer is that Tommy Fleetwood is not significantly flipping (bending) his left wrist or supinating his left forearm during that time period and he is controlling the rate-of-closure of his clubface (relative to his clubhead arc) by optimally controlling the rate of external rotation of his left humerus so that he can keep his clubface continuously square relative to his clubhead arc between P7 and P7.4. Tommy Fleetwood obviously has a "maxed-out" left forearm supination appearance at P8, but the left forearm supination phenomenon that is needed to achieve that "look" is only happening between P7.7 and P8 (representing what is called a "finish swivel action" in TGM terminology) and it is not happening continuously in an uninterrupted manner all the time between impact and P8. If the left forearm was supinating rapidly between impact and P7.4 then the clubshaft would bypass his left arm (from an angular rotational perspective) and his clubface would have a much higher rate-of-closure - as seen in Luke Donald's P7 => P7.4 followthrough time period. Further proof that Tommy Fleetwood is not significantly supinating his left forearm between impact and P7.4 can be derived from studying close-up views of his followthrough action - as seen in these close-up capture images of his followthrough action.

Image 1 is at impact, image 2 is at P7.4, image 3 is at P7.7 and image 4 is

at P8.

I have a placed a green dot in the middle of his left antecubital fossa (elbow pit) and 3 red dots in a straight-line over his left radial bone just above his left wrist crease. A changing rotational relationship between the green dot and the red dots (where the red dots rotate faster counterclockwise than the green dot) would reflect the presence of left forearm supination.

Note that you cannot see his left antecubital fossa in image 1 (impact) because his left humerus is internally rotated at impact. Note that the back of his left hand and watchface area of his left lower forearm is facing the camera at impact - which is expected considering the fact that he uses a strong left hand grip.

Note that you can clearly see the green dot at P7.4 (image 2) which means that he has significantly rotated his left humerus counterclockwise between impact and P7.4. Note that the red dots (signifying the position of his left lower radial bone) have not likely rotated counterclockwise more than his green dot (signifying the position of his left antecubital fossa) between impact and P7.4 and that suggests that there is no significant amount of left forearm supination happening between impact and P7.4.

Note that the back of his left hand and watchface area of his left lower forearm continues to rotate counterclockwise between P7.4 (image 2) and P7.7 (image 3) and that it is primarily due to continued external rotation of his left humerus without any additional left forearm supination component (as evidenced by the fact that the red dots are not rotating counterclockwise faster than the green dot between P7.4 and P7.7).

It is very important to note a few other biomechanical features of Tommy Fleetwood's DH-hand release action (delayed full-roll subtype) that is happening between impact and P7.4 (other than the previously mentioned fact that he externally rotates his left humerus in a controlled manner while avoiding any left forearm supination or any left wrist bending).

i) He does not stall the forward motion of his left arm between P7 and P7.4 (as happens in Luke Donald's P7 => P7.4 followthrough action) and his left arm is still swinging targetwards at the same angular velocity as his clubshaft thereby ensuring that the clubshaft does not bypass his left arm (from an angular rotational perspective) during that time period.

ii) He maintains a slightly bent right arm and slightly bent right wrist between P7 and P7.4. The biomechanical phenomenon of maintaining a bent right arm and a bent right wrist during the P7 => P7.4 followthrough time period is called "not running-out-of-right arm" and to achieve that desirable feature of a DH-hand release action, a golfer has to drive the right shoulder under the chin while simultaneously opening the pelvis and upper torso to the target. By contrast, if you look at the capture images of Luke Donald's P7 => P7.4 followthrough, you will notice that he prematurely "runs-out-of-right arm" (which causes his right arm and right wrist to prematurely straighten).

There is another subtype of DH-hand release action called the no-roll subtype - as seen in the following capture images of Charley Hoffmann's followthrough.

Note that Charley Hoffmann does not allow his clubshaft to bypass his left arm between impact (image 1) and P7.7 (image 5) from an angular rotational perspective, which means that he is essentially swinging his left arm targetwards at the same angular velocity as his released clubshaft. Note that he is not externally rotating his left humerus or supinating his left forearm or bending his left wrist during the P7 => P7.7 time period. Note that he is still maintaining a bent right arm and bent right wrist during his followthrough and he is not prematurely "running-out-of-right arm" - and that means that he must continue to actively drive his right shoulder under his chin while opening his pelvis and upper torso to the target. A golfer has to be extraordinarily flexible to be capable of performing a *no-roll subtype of DH-hand release action when hitting a wood or long iron, but it has the great advantage of allowing a golfer to keep the clubface square to the clubhead arc to well beyond impact. By contrast, if a golfer uses a non-DH hand release action secondary to excessive left forearm supination happening between P7 and P7.4 (like Luke Donald), then he is going to have a much higher ROC (rate-of-closure) of his clubface during his clubhead's travel time through the immediate impact zone between impact and P7.4. A student-golfer may wonder why a much higher ROC of the clubface happening in the followthrough after impact will be a disadvantage because the ball is long gone by the time the club reaches the P7.2 position, but the reality is that the biomechanics needed to execute a DH-hand release action (which ensures a low ROC of the clubface between P7 and P7.2) must start fractionally before impact at ~P6.9 and they must continue through impact to P7.2 (or even longer to P7.4). By contrast, if the golfer has a very high ROC of his clubface between P7 and P7.4 due to excessive left forearm supination, then it is very likely that he had a high ROC of his clubface through impact between P6.9 => P7.1 due to the same biomechanical phenomenon of excessive left forearm supination.

(* I have described the difference between a no-roll DH hand release action and a delayed full-roll hand release action in great detail in this review paper called "Hand Release Actions Through the Impact Zone" and also in part 7 of my video project on "How to Perform a Golf Swing Like a PGA Tour Golfer")

Many modern-day professional golfers (like Jordan Spieth, Justin Thomas, Dustin Johnson,, and Adam Scott) are using a DH-hand release action between impact and P7.2+ and that allows them to have a very stable clubface that manifests a very low ROC throughout the immediate impact zone between P7 and P7.2 (and often even further to P7.4+).

Here are capture images of their followthrough action - note their stable clubface, which has a very low ROC, during their clubhead's travel passage through the immediate impact zone between impact and P7.2 (and sometimes even further to P7.4+).

Jordan Spieth

Justin Thomas

Dustin Johnson

Adam Scott

Now, I can readily imagine that many golfers, and golf instructors, are not

going to be convinced that Tommy Fleetwood is not significantly supinating

his left forearm between impact and P7.4 - based on those red dots not

rotating counterclockwise faster than the green dot in those capture images

that I have presented - and they are going to demand 3-D proof that a DHer

can really stop his left forearm supination temporarily between P7 and P7.4

and then suddenly start supinating rapidly again as he transitions into a

finish swivel action during the later followthrough between P7.4 and P8. So,

here is the proof - using the professional golfer, Jon Rahm,

as an example of a DHer (drive-holder).

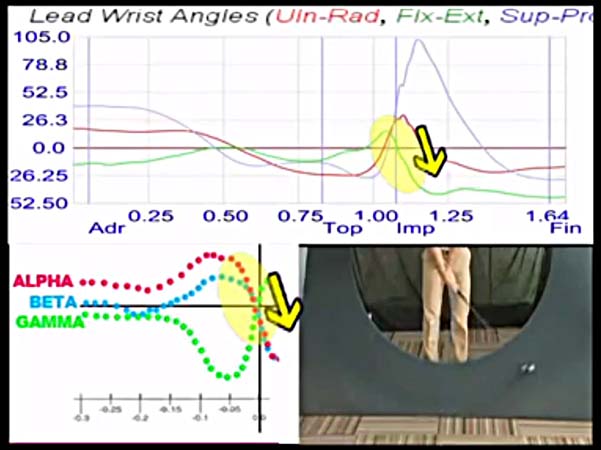

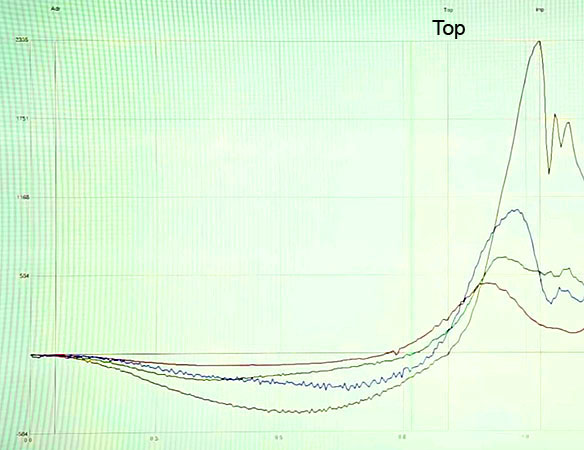

Consider Jon Rahm's 3-D graph.

The green graph is his left wrist flexion-extension graph, the red graph is his left wrist radial deviation-ulnar deviation graph and the blue graph (lowest graph) is his left forearm supination-pronation graph. Note that there is a temporary plateau in his left forearm supination graph immediately post-impact (see yellow arrow) which indicates that he is not continuing to supinate his left forearm in a continuously uninterrupted manner for a short time period between impact and P7.2+, before he again starts to rapidly supinate his left forearm again during his finish swivel action. Also, note that there is a plateau in his left wrist flexion graph that happens simultaneously during that same impact to P7.2+ time period (see the green graph between the red arrow and the blue arrow) - where he comes into impact with a bowed left wrist and maintains approximately the same degree of left wrist bowing for a short time period post-impact.

Do capture images of Jon Rahm's early followthrough show the same evidence seen in that 3-D graph?

Here are capture images of Jon Rahm's early followthrough action.

Image 1 is at impact, image 2 is at P7.1 and image 3 is at about P7.3.

Note that Jon Rahm is a perfect example of a DHer by noting that his clubshaft does not bypass his left arm (from an angular rotational perspective) between impact and P7.3 and that he keeps the clubface continuously square to the clubhead arc during the P7 => P7.3 time period.

Note that Jon Rahm comes into impact with a bowed left wrist and that he maintains roughly the same degree of left wrist palmar flexion between impact and P7.3.

Note that there is no visual evidence to suggest that Jon Rahm is continuing to supinate his left forearm in a continuously uninterrupted manner between impact and P7.3 (like Luke Donald). Note that he is controlling the degree of counterclockwise rotation of the back of his bowed left wrist (and therefore clubface) between impact and P7.3 by controllably rotating his left humerus in a counterclockwise direction, and that defines him as using a delayed full-roll subtype of DH-hand release action.

I believe that all professional golfers have to use left forearm supination pre-impact in order to square the clubface by impact and that the amount of required left forearm supination is inversely proportional to left hand grip strength. However, it is possible for a professional golfer to use variable amounts of left forearm supination post-impact between P7 and P8. A professional golfer (like Charley Hoffmann in those capture images of Charley Hoffmann's followthrough action) may decide to use no left forearm supination between P7 and P8 because he uses a no-roll subtype of DH-hand release action and he never transitions into a finish swivel action before P8. Alternatively, a professional golfer (like Jon Rahm) may decide to use a delayed-full roll subtype of DH-hand release action between impact and P7.2 (or even further to P7.4) before transitioning into a finish swivel action at some time point between P7.4 and P8. Alternatively, a professional golfer may decide to use a non-DH hand release action by using a significant amount of left forearm supination between impact and P7.4 (like Luke Donald) and where the left forearm continues to supinate in a continuously uninterrupted manner between ~P6.5 and P7.4. The advantage of using a DH-hand release action (rather than a non-DH hand release action due to the use of a significant amount of left forearm supination between impact and P7.4) is the fact that it allows a professional golfer (or skilled amateur golfer) to have a very low ROC of his clubface through the immediate impact zone between impact and P7.2 (or even better to P7.4+).

I can readily imagine a student golfer (developing golfer), who has never heard of the concept of a drive-hold hand release action, asking this relevant question-: "What are the key features of a drive-hold hand release action and what are the "do's and dont's" that the golfer must perform in order for him to become an exemplary DHer?"

I will offer some brief pointers in an answer to that question.

First of all, a student golfer needs to understand that left forearm supination is obligatory in the late downswing's pre-impact time period in order to acquire a square clubface by impact (as described in topic number 1), and that the amount of required left forearm supination is inversely proportional to left hand grip strength. Secondly, he needs to understand that post-impact left forearm supination is optional and it is only necessary if he wants, or needs, to perform a finish swivel action that swivels the clubshaft back onto the inclined plane after P7.2 (or preferably after P7.4). It requires tremendous flexibility and a very good torso rotation through impact in order to perform a no-roll DH-hand release action (like Charley Hoffmann), who does not perform a finish swivel release action between P7 and P7.8. Most amateur golfers would find it much easier, and much more biomechanically comfortable, to perform a finish swivel action at an earlier stage during their followthrough - but they need to delay that finish swivel action if they want to be a DHer who maintains a stable clubface, that has a low ROC, between P7 and P7.2. To ensure that the clubface remains square to the clubhead arc to at least P7.2 (and even better to P7.4) he should avoid using any significant left forearm supinatory motion, or any significant left wrist flipping type of motion, through the immediate impact zone between P7 and P7.2+.

Consider the following series of capture images of Roger Federer performing a backhanded tennis stroke (where he is hitting a straight shot without slice spin or top spin).

Image 1 shows him at his P4 position. Note that the back of his lead hand and racquet face is not vertical to the ground and it is angled back slightly. To get a square racquet face at impact (image 4), where the racquet face is vertical to the ground, he needs to supinate his lead forearm during his forward swing action. The amount of needed lead forearm supination is very small because Roger Federer adopts a strong lead hand grip for his backhanded tennis shots.

However, look at what he does between impact (image 4) and P8+ (image 5). Note that he abducts his lead arm away from his body without supinating his lead forearm between impact and P8 and that allows him to keep his racquet face continuously vertical to the ground during his followthrough action, and that followthrough technique represents a perfect example of a DH-hand release action (where the racquet never bypasses his lead arm from an angular rotational perspective).

The same principle applies to a golf swing action - so, consider Sasho MacKenzie's one-arm golf swing's followthrough action at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GgF_9IfROAU

Image 1 is at P7.4, image 2 is at P7.8 and image 3 is at P8.3.

Note that he never bends (extends) his flat lead wrist, or supinates his lead forearm, or externally rotates his lead humerus, during his entire followthrough action - while he abducts his lead arm progressively further away from his body. That no-roll type of followthrough technique allows him to keep the clubshaft straight-in-line with his lead arm during his entire followthrough action and it also allows him to keep the clubface square to his clubhead arc throughout his entire followthrough action. Sasho Mackenzie's followthrough represents a perfect example of a no-roll subtype of DH-hand release action where the clubface is square to the clubhead arc to well beyond P7.4.

Note that his torso is only slightly open to the ball-target line during his entire followthrough action and that he does not continue to rotate his pelvis and upper torso more clockwise during his followthrough action. Note that his rear shoulder remains behind his chin and it never bypasses his chin during his followthrough action. That type of followthrough technique, where the rear shoulder does not move forward under the chin in a targetwards direction, would therefore not be applicable to a two-handed golf swing technique because the golfer would "run-out-of-rear arm" and his rear hand could never reach his lead hand at all time points during the followthrough action.

To perform the same no-roll subtype of DH-hand release action when using two arms, a golfer will need to rotate his pelvis and upper torso much more open during his followthrough action so that his rear shoulder socket can get closer to the target as both arm arms are extended away from the body. To prevent the problem of "running-out-of-rear arm" the golfer will need to keep the rear shoulder moving continuously targetwards throughout the followthrough action - as seen in these capture images of Charley Hoffmann's no-roll subtype of DH-hand release action.

Note how Charley Hoffmann's upper torso and his two shoulder sockets rotate

counterclockwise in a continuous manner between impact (image 1) and

P7.7 (image 5). Note that he can still maintain a slightly bent right wrist

all the way to P7.7, which is a good indicator that he is not

"running-out-of-right arm". Note that he does not bend (extend) his lead

wrist, or supinate his lead forearm, or externally rotate his lead humerus,

between P7 and P7.7 and that allows him to keep the clubshaft

straight-in-line with his lead arm (from an angular rotational perspective)

all the way from P7 to P7.7 and it also allows his to keep his clubface

square to his clubhead arc during that entire followthrough time period.

It takes tremendous flexibility to use that no-roll subtype of DH-hand release action, especially when swinging longer clubs, so many professional golfers only use that technique for their short iron shots.

Consider Tiger Woods performing a more limited version of a no-roll subtype of DH-hand release action in this swing video at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NSEfbgRheEA

Here are capture images from the swing video.

Note that Tiger Woods is using the no-roll subtype of DH-hand release action

from impact to P7.4 (image 1) and that he then subsequently transitions into

a finish swivel action later in his followthrough action (images 2 & 3). Note

that he does not bend his lead wrist, or supinate his lead forearm, or

externally rotate his lead humerus, between P7 and P7.4 - and that allows him

to avoid having the clubshaft bypass his lead arm (from an angular

rotational perspective) and it also allows him to keep the clubface

continuously square to the clubhead arc. Note how much he has to

rotate his upper torso counterclockwise during his P7 => P7.4 followthrough

action, and note how much his right shoulder moves targetwards under his chin,

and that allows him to maintain a slightly bent right elbow and slightly bent

right wrist all the way to P7.4, and thereby avoid a "running-out-of-right

arm" problem.

Because it is physically easier to use the delayed full-roll subtype of DH-hand release action (as seen in those capture images of Tommy Fleetwood's' followthrough action), it is the more common type of DH-hand release action used by professional golfers (like Dustin Johnson, Jon Rahm, Adam Scott and Justin Thomas) who use a DH-hand release action technique. In this subtype of DH-hand release action, a golfer allows the left humerus to abduct and externally rotate at a perfectly controlled speed that ensures that the left arm and clubshaft have the same angular rotational velocity, and that biomechanical action prevents the clubshaft from bypassing the left arm (from an angular rotational perspective) during the early followthrough time period - while the golfer simultaneously avoids any left wrist bending, or left forearm supination, from happening during that early followthrough time period (that precedes the transition to a finish swivel action).

As I have previously mentioned, there are two critical biomechanical actions that a golfer must avoid if he wants to be a DHer - any left wrist flipping, or left forearm supination, biomechanical actions between P7 and P7.2 (or even better to P7.4).

Let's consider what factors could cause left wrist flipping through impact.

Left wrist flipping (left wrist extension) through impact could be an intentional action if the golfer deliberately uses the rotation-about-the-coupling point hand release action recommended by some golf instructors (eg. Brian Manzella, Michael Jacobs and Richard Franklin).

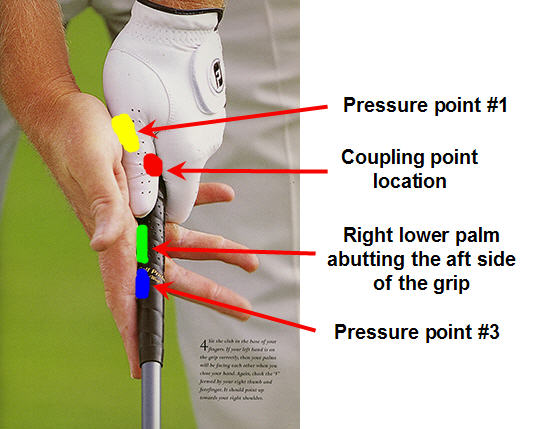

Rotation-about-the-coupling point hand release action - as described in a Richard Franklin video (https://youtu.be/k0r3l0QdAqg).

In this illustration, Richard Franklin is demonstrating a rotation-about-the coupling point hand release action. The green graph represents the left wrist flexion => extension graph and one can see how the left wrist extends rapidly through impact (as also seen in the small photo image in the lower right hand corner). In that type of hand release action (which actually start in the late downswing) a golfer is encouraged to i) actively push against the aft side of the clubshaft with the right hand while ii) stalling the forward motion of the left hand through impact as the golfer simultaneously iii) pulls the top of the club handle back (away from the target) with the left hand so that the dual hand motions induce a rotation of the club handle around the coupling point (which is a point midway between the hands on the club handle). Note how a rotation-about-the-coupling point hand release action causes the clubshaft to bypass the hands. If the clubshaft abruptly bypasses the hands through impact, then the fulcrum point of the clubshaft motion becomes situated at the level of the hands (and not at the level of the left shoulder socket as occurs in a DHer). That will cause the clubhead arc's radius to be radically shortened and it will cause the clubhead to move more quickly inside-left thereby causing the clubface to close more relative to the ball-target line even if the golfer avoids any left wrist circumduction motion at the level of the left wrist (= left wrist rolling motion due to the combination of left wrist extension + left wrist radial deviation) that can potentially increase the degree of clubface closure if it happens simultaneously with the left wrist extension phenomenon. There is also the problem of timing the left wrist extension phenomenon so that the golfer can avoid any pre-impact left wrist flipping, but perfect timing is obviously difficult to achieve on a consistent basis when swinging a driver at clubhead speeds of 100-125mph through impact. Hopefully, any reader of this review paper can more easily understand why a rotation-about-the-coupling point hand release action will invariably produce a non-DH hand release action and potentially a higher ROC of the clubface between P7 and P7.2 (if it is associated with a significant degree of left wrist circumductory motion that rolls the club handle while the left wrist bends).

Left wrist flipping between P7 and P7.2 can also be an unintentional action if the golfer stalls the forward motion of the left arm/hand and/or if the golfer unintentionally applies too much push-pressure against the aft side of the club handle (below the coupling point) with the right hand in a slap-hinge manner. That type of non-DH hand release action is much more likely to occur in golfers who use a swing-hitting technique where they actively straighten the right arm and/or right wrist during the late downswing in an inconsistent manner from swing-to-swing.

Now, let's consider factors affecting the amount of left forearm supinatory motion that can happen through impact - starting in the late downswing and continuing in an interrupted manner to P7.4+.

I believe that if a golfer wants to be a DHer who wants to avoid any significant amount of left forearm supination from happening between P7 and P7.4, then he needs to understand the "forces" that can potentially produce a continuously uninterrupted left forearm supinatory motion through impact.

The worst-case scenario that will invariably produce a continuously uninterrupted left forearm supinatory motion through impact, and therefore a non-DH hand release action, is the use of active muscular forces in the late downswing that promote right forearm pronation and/or left forearm supination.

Unfortunately, many golf instructors, like AJ Bonar, are advocates of an active roll motion of the two forearms through impact, which is called a hand crossover release action.

Here is an extract from a golf magazine article where AJ Bonar describes his hand crossover release action: "About two or three feet before your hands reach impact, assertively rotate them toward the target. Imagine you're gripping a screwdriver and turning it counterclockwise. This closes the clubface, generating big-time power."

AJ Bonar often states that a golfer should "feel" that he is rolling the top of the clubface over the bottom half of the clubface through impact by using his recommended "active screwdriver move".

I think that AJ Bonar's recommended "hand crossover release action" is irrational golf instructional advice that will invariably produce a high ROC of the clubface through the immediate impact zone between P7 and P7.2, and it is a "move" that any golfer, who wants to learn how to become a DHer, should rigorously avoid using in his golf swing action.

I believe that any left forearm supination happening in the late downswing's PA#3 release action (which is needed to square the clubface by impact) should be passive (and not active).

What do I mean by a passive left forearm supinatory motion?

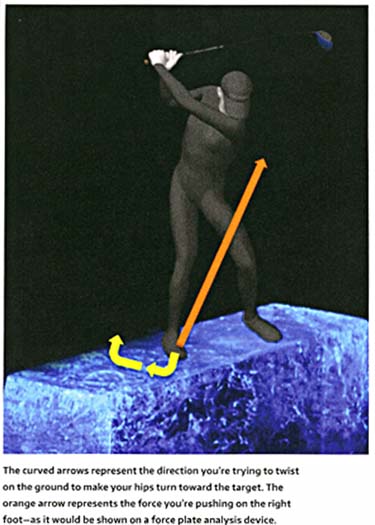

To better understand the term "passive" with respect to the left forearm's supinatory motion that can happen between P6 and P8, I think that a golfer should try to understand the physical phenomenon called the RYKE effect.

Here is link to a you-tube video where Kevin Ryan describes the RYKE effect - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PyeDPyfex9M&t=116s

What Kevin Ryan did was modify the central arm of a double pendulum swing model by inserting a passive cylindrical joint device into the peripheral end of the central arm. That allows the peripheral end of the central arm to rotate about its longitudinal axis thereby mimicking a passive left forearm supinatory motion. If you watch the video, you will note that even a small transverse force that moves the clubshaft off-plane can induce the RYKE effect where the clubshaft's single-in-plane pendular motion is changed to a conical pendular motion, and you will also note that the clubface will rotate through impact in a continuously uninterrupted manner (as seen in the 3D graph presented by Tyler Ferrell).

Here are capture images from Kevin Ryan's video showing what effect the RYKE effect phenomenon will have on a golfer's golf swing action.

Images have been flipped horizontally to convert the left-handed golfer into a right-handed golfer

Image 1 is at P6, image 2 is at P6.6, image 3 is at impact and image 4 is at

P7.5.

Note how his left forearm progressively supinates between P6 and impact, and that is obligatory if this golfer (who uses a neutral left hand grip) wants to square the clubface by impact. However, note how the golfer continues to supinate his left forearm in a continuously uninterrupted manner between impact and P7.5, which produces a rolling subtype of non-DH hand release action where the clubshaft bypasses the left arm (as seen in Luke Donald's early followthrough action).

The speed of rotation of the clubshaft (around its longitudinal axis) through the immediate impact zone between P7 and P7.2 in a non-DH hand release action due to left forearm supination can vary considerably in different golfers because the speed of left forearm supination can vary considerably, and if it happens very fast it will result in an exaggerated rolling subtype of non-DH hand release action, which I call a *roller subtype of non-DH hand release action.

(* When I use the term "rolling" subtype with respect to a non-DH hand release action that is due to left forearm supination, that means that the speed of clubface rolling per unit degree of clubhead travel along the clubhead arc is much slower because the speed of left forearm supination is slower - and when I use the term "roller" subtype that means that the speed of clubface rolling per unit degree of clubhead travel is much faster because the speed of left forearm supination is faster)

Here is an animated gif example of Phil Mickelson performing a roller subtype of non-DH hand release action between P7 and P7.2.

Note how Phil Mickelson's lead hand rotates continuously

clockwise due to an unrestrained lead forearm supinatory motion through

impact. The RYKE effect may be in play, but it cannot be the only factor

responsible for his uncontrolled lead forearm supination through impact

because he has a small accumulator #3 angle at the time of clubshaft rolling,

and he may be subconsciously (non-intentionally) adding some lead forearm

supinatory muscular torque, +/- some rear forearm pronatory muscular torque,

during his late downswing after P6.7.

Some golf instructors actually recommend a rolling type of hand release action by advising golfers to relax their arms/forearms so that the lead forearm can rotate passively through impact under the influence of the RYKE effect - see this you-tube video at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UAIdIdWoe9g&t=127s called the "L to L Drill - the Most Important Golf Lesson You Need to Know" by Mike Malaska. Note how Mike Malaska is mimicking a roller hand release action - first with his left arm, then with his right arm, and then with both arms together.

If a golfer wants to become a DHer, then he cannot afford to heed Mike Malaska's advice because it will invariably result in a rolling subtype of non-DH hand release action through impact.

So, what can a student-golfer (developing golfer), who wants to become a DHer, do in his late downswing and early followthrough to avoid becoming a non-DHer, who performs a rolling subtype of non-DH hand release action between P7 and P7.2?

First of all, if a golfer wants to become a DHer, then he needs to use a passive left forearm supinatory motion in his late downswing in order to get a square clubface by impact. If the left forearm supinatory motion is passive, and operating in accordance with the passive dynamics underlying the RYKE phenomenon, then the golfer should think of the counterclockwise rolling motion of the left forearm automatically/naturally slowing down as the left hand approaches impact - as the left forearm gets back to its same resting state of pronation that existed at address. The resting state of pronation at address depends on left hand grip strength, and golfers who have a strong left hand grip at address will naturally have more left forearm pronation at address than a golfer who has a weak-or-neutral left hand grip. In other words, a golfer should not think of deliberately rolling the back of the left hand counterclockwise beyond its resting state of pronation at address. So, if a golfer adopts a weak or neutral left hand grip at address where the back of the left hand roughly faces the target at address, then he should think of getting to impact with the back of his left hand facing the target to roughly the same degree. His second ancillary thought must be the "idea" of avoiding any stalling of the targetwards motion of the left arm/hand at impact and he must ensure that the left arm/hand continuously moves targetwards through impact to P7.2 (or even better to P7.4) at an angular velocity that perfectly matches the targetwards angular velocity of the clubshaft, and that will ensure that the clubshaft remains straight-line-aligned with the left arm all the way to P7.4. Here is an example - Kelli Oride.

Kelli Oride swing video - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p7hBadAiMcA

Here are capture images from Kelli Oride's swing video.

Image 1 is at impact, image 2 is at P7.2 and image 3 is at P7.4. Image 4 is

a composite image showing the targetwards motion of her left hand and

clubshaft/clubhead between P7 and P7.4.

The diagram depicts her left shoulder socket in black, her left arm in red and her clubshaft in green. The blue dot represents her left hand and the orange dot represents the clubhead.

Note how Kelli Oride keeps the back of her left hand continuously facing the target between P7 and P7.4 and there is very little counterclockwise rotation of her left hand happening between P7 and P7.4. Also, note that her left hand (represented by the blue dot in the diagram) moves targetwards at an angular velocity that perfectly matches the angular velocity of the clubhead (orange dot) and that action allows Kelli Oride to keep her LAFW intact, and it thereby prevents the clubshaft from bypassing her left arm (from an angular rotational perspective).

Another swing thought that is very useful for a golfer, who wants to become a DHer (like Kelli Oride), is how to usefully use the right arm/hand to synergistically assist the left arm/hand in efficiently performing a DH-hand release action. Note that Kelli Oride does not fully straighten her right arm, or her right wrist, between P7 and P7.4 and she straightens her right elbow at an optimum speed that can allow her right palm to continuously apply push-pressure against PP#1 (which is located over the base of her left thumb) and that small amount of push-pressure that is continuously being applied by the right palm against PP#1 can help her to optimally control the speed of forward (targetwards) motion of the left hand between P7 and P7.4 - while she simultaneously avoids any unwanted right forearm pronation, or left forearm supination, during that same P7 => P7.4 time period. To achieve that goal of fruitfully using the straightening right arm to synergistically assist her left arm/hand to more efficiently execute a DH-hand release action through the immediate impact zone, Kelli Oride must avoid "running-out-of-right arm" by also ensuring that her right shoulder continuously moves forward (targetwards) under her chin at an optimum speed.

Contrast Kelli Oride's perfectly executed DH-hand release action with the roller hand release action often seen in Phil Mickelson's driver swing action.

Here is a capture image of Phil Mickelson's driver swing action at the P7.4 position.

Note that Phil Mickelson is performing a roller subtype of non-DH hand release action, which causes the clubface to roll closed relative to his clubhead arc. Note that his rear palm is not even in contact with his lead thumb at PP#1 because he has "run-out-of-rear arm" - evidenced by the fact that i) his rear shoulder is far back and it has not moved targetwards under his chin and ii) his rear arm is fully straight and iii) his rear forearm has fully pronated and iv) his rear wrist has fully straightened.

If a golfer "runs-out-of-right arm" during the late downswing, or early followthrough, then he cannot usefully use the straightening right arm/hand to synergistically assist the left arm/hand in efficiently performing a DH-hand release action through impact. Now, contrast Phil Mickelson's non-DH hand release action (roller subtype) with Jordan Spieth's superb execution of a DH-hand release action.

Capture images from a Jordan Spieth driver swing video.

Note that Jordan Spieth is performing a perfectly executed DH-hand release action between impact (image 1) and P7.5 (image 3) - note that he keeps the clubface continuously square to his clubhead arc and that he continuously prevents his clubshaft from bypassing his left arm (from an angular rotational perspective). Note how he keeps his right shoulder continuously moving targetwards under his chin while he opens his upper torso more to the target, and note how he maintains a slightly bent right arm and a slightly bent right wrist all the way to P7.5 - and those biomechanical elements are all "indicator signs" of a golfer who is not "running-out-of-right arm".

Here are close-up views of Jordan Spieth's hands between impact and P7.5.

Image 1 is at impact, image 2 is at P7.2 and image 3 is at P7.5.

Jordan Spieth uses a Vardon style of left/right hand grip that allows him to position his right palm over the base of his left thumb at address.

Note that Jordan Spieth's right palm is closely applied against his left thumb throughout his followthrough action, and that allows any push-pressure being continuously applied by his right palm against PP#1 (which is located over the base of his left thumb) to synergistically assist his left hand in more efficiently executing a DH-hand release action between P7 and P7.4 if the right arm straightens at an optimal speed that allows the right hand to move targetwards at the same speed as the left hand. I obviously don't know if Jordan Spieth's right palm is continuously applying a steady amount of push-pressure against the base of his left thumb between P7 and P7.4 because no golf researcher has ever measured the amount of push-pressure being applied by the right palm against PP#1 during a golfer's followthrough action - but I can readily imagine that the continuous application of push-pressure by the right palm against PP#1 (which is located over the base of the left thumb) by exactly the optimum amount could be extremely useful in helping Jordan Spieth's left arm/hand more efficiently perform a DH-hand release action between P7 and P7.4. If a golfer uses a perfectly controlled straightening of the right arm between P7 and P7.4 to work in perfect synchrony with the left arm, which is swinging targetwards at an angular velocity that matches the angular velocity of the released club, then he can also ensure that the right forearm does not excessively pronate during the P7 => P7.4 time period. Note that Jordan Spieth's right palm remains behind the grip between P7 and P7.4 and it never rolls over the left hand (as seen in a hand crossover hand release action) and that helps Jordan Spieth to avoid the automatic/natural "left forearm supination + right forearm pronation" that would happen if the RYKE effect was unrestrained.

In summary, a DHer must constrain the RYKE effect to ensure that it only happens pre-impact, and not post-impact, by using a number of biomechanical elements post-impact that characterise a DH-hand release action.

Those biomechanical elements may include some, or all, of the following features:

i) The golfer must avoid stalling the targetwards motion of the left arm at impact and he must ensure that he continues to swing the left arm targetwards at an angular velocity that matches the angular velocity of the released club, so that the clubshaft does not bypass the left arm between P7 and P7.2 (or even better to P7.4).

ii) The golfer must think of keeping the back of the GFLW (or AFLW) roughly facing the target for longer through impact to at least P7.2, and he must avoid allowing the back of the GFLW (or AFLW) to rotate too much counterclockwise due to an unrestrained RYKE effect (that is manifested biomechanically as a continuously uninterrupted left forearm supinatory motion happening between P7 and P7.2, and even beyond P7.2).